Abstract

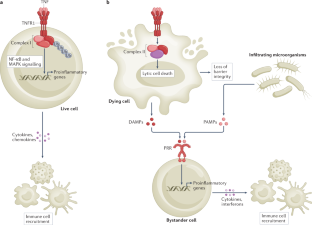

Tumour necrosis factor (TNF) is a central cytokine in inflammatory reactions, and biologics that neutralize TNF are among the most successful drugs for the treatment of chronic inflammatory and autoimmune pathologies. In recent years, it became clear that TNF drives inflammatory responses not only directly by inducing inflammatory gene expression but also indirectly by inducing cell death, instigating inflammatory immune reactions and disease development. Hence, inhibitors of cell death are being considered as a new therapy for TNF-dependent inflammatory diseases.

This is a preview of subscription content, access via your institution

Access options

Access Nature and 54 other Nature Portfolio journals

Get Nature+, our best-value online-access subscription

$32.99 / 30 days

cancel any time

Subscribe to this journal

Receive 12 print issues and online access

$259.00 per year

only $21.58 per issue

Buy this article

- Purchase on SpringerLink

- Instant access to the full article PDF.

USD 39.95

Prices may be subject to local taxes which are calculated during checkout

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Anderton, H., Wicks, I. P. & Silke, J. Cell death in chronic inflammation: breaking the cycle to treat rheumatic disease. Nat. Rev. Rheumatol. 16, 496–513 (2020).

Carswell, E. A. et al. An endotoxin-induced serum factor that causes necrosis of tumors. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 72, 3666–3670 (1975). TNF is identified as a serum factor that could induce necrosis of tumours in patients following acute bacterial infections. The necrotizing factor was named ‘tumour necrosis factor’ or ‘TNF’.

Coley, W. B. The treatment of malignant tumors by repeated inoculations of erysipelas: with a report of ten original cases. Am. J. Med. Sci. 105, 487–511 (1893).

Coley, W. B. The treatment of inoperable sarcoma by bacterial toxins (the mixed toxins of the Streptococcus erysipelas and the Bacillus prodigiosus). Proc. R. Soc. Med. 3, 1–48 (1910).

Shear, M. J. & Perrault, A. Chemical treatment of tumors. IX. Reactions of mice with primary subcutaneous tumors to injection of a hemorrhage-producing bacterial polysaccharide. J. Natl Cancer Inst. 44, 461–476 (1944).

Pennica, D. et al. Human tumour necrosis factor: precursor structure, expression and homology to lymphotoxin. Nature 312, 724–729 (1984).

Marmenout, A. et al. Molecular cloning and expression of human tumor necrosis factor and comparison with mouse tumor necrosis factor. Eur. J. Biochem. 152, 515–522 (1985).

Fransen, L. et al. Molecular cloning of mouse tumour necrosis factor cDNA and its eukaryotic expression. Nucleic Acids Res. 13, 4417–4429 (1985).

Aggarwal, B. B., Eessalu, T. E. & Hass, P. E. Characterization of receptors for human tumour necrosis factor and their regulation by gamma-interferon. Nature 318, 665–667 (1985).

Loetscher, H. et al. Molecular cloning and expression of the human 55 kd tumor necrosis factor receptor. Cell 61, 351–359 (1990).

Schall, T. J. et al. Molecular cloning and expression of a receptor for human tumor necrosis factor. Cell 61, 361–370 (1990).

Smith, C. A. et al. A receptor for tumor necrosis factor defines an unusual family of cellular and viral proteins. Science 248, 1019–1023 (1990).

Heller, R. A. et al. Complementary DNA cloning of a receptor for tumor necrosis factor and demonstration of a shed form of the receptor. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 87, 6151–6155 (1990).

Balkwill, F. Tumour necrosis factor and cancer. Nat. Rev. Cancer 9, 361–371 (2009).

Beutler, B. et al. Identity of tumour necrosis factor and the macrophage-secreted factor cachectin. Nature 316, 552–554 (1985).

Martens, S., Hofmans, S., Declercq, W., Augustyns, K. & Vandenabeele, P. Inhibitors targeting RIPK1/RIPK3: old and new drugs. Trends Pharmacol. Sci. 41, 209–224 (2020).

Mifflin, L., Ofengeim, D. & Yuan, J. Receptor-interacting protein kinase 1 (RIPK1) as a therapeutic target. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 19, 553–571 (2020).

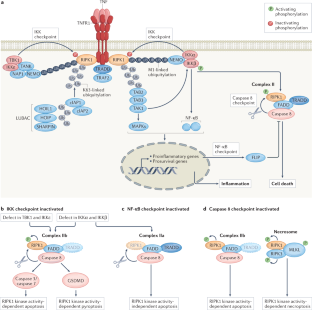

Ting, A. T. & Bertrand, M. J. M. More to life than NF-kappaB in TNFR1 signaling. Trends Immunol. 37, 535–545 (2016).

Delanghe, T., Dondelinger, Y. & Bertrand, M. J. M. RIPK1 kinase-dependent death: a symphony of phosphorylation events. Trends Cell Biol. 30, 189–200 (2020).

Lork, M., Verhelst, K. & Beyaert, R. CYLD, A20 and OTULIN deubiquitinases in NF-kappaB signaling and cell death: so similar, yet so different. Cell Death Differ. 24, 1172–1183 (2017).

Micheau, O. & Tschopp, J. Induction of TNF receptor I-mediated apoptosis via two sequential signaling complexes. Cell 114, 181–190 (2003). This is the first study reporting that, in contrast to other death receptor of the TNFR family, TNFR1-mediated cell death relies on the assembly of a cytosolic, receptor-dissociated, caspase 8-activating complex (complex II) that originates from the membrane-bound receptor signalling complex (complex I).

Orning, P. et al. Pathogen blockade of TAK1 triggers caspase-8-dependent cleavage of gasdermin D and cell death. Science 362, 1064–1069 (2018). This study demonstrates that inhibition of TAK1 by the Yersinia effector YopJ causes RIPK1-dependent caspase 8-mediated cleavage of GSDMD and pyroptosis.

Demarco, B. et al. Caspase-8-dependent gasdermin D cleavage promotes antimicrobial defense but confers susceptibility to TNF-induced lethality. Sci. Adv. 6, eabc3465 (2020).

Schwarzer, R., Jiao, H., Wachsmuth, L., Tresch, A. & Pasparakis, M. FADD and caspase-8 regulate gut homeostasis and inflammation by controlling MLKL- and GSDMD-mediated death of intestinal epithelial cells. Immunity 52, 978–993 (2020).

Wang, L., Du, F. & Wang, X. TNF-alpha induces two distinct caspase-8 activation pathways. Cell 133, 693–703 (2008). This study demonstrates that cIAP1/cIAP2-mediated ubiquitylation controls the yet-to-be-discovered IKK checkpoint independently of NF-κB. It reveals the existence of TNFR1 complex IIa and complex IIb.

Wilson, N. S., Dixit, V. & Ashkenazi, A. Death receptor signal transducers: nodes of coordination in immune signaling networks. Nat. Immunol. 10, 348–355 (2009).

Dondelinger, Y. et al. NF-kappaB-independent role of IKKalpha/IKKbeta in preventing RIPK1 kinase-dependent apoptotic and necroptotic cell death during TNF signaling. Mol. Cell 60, 63–76 (2015). This is the first study describing the IKK checkpoint, demonstrating that the IKK complex phosphorylates RIPK1 to prevent TNF-induced RIPK1 kinase activity-dependent cell death, independent of its function in NF-κB activation.

Lafont, E. et al. TBK1 and IKKepsilon prevent TNF-induced cell death by RIPK1 phosphorylation. Nat. Cell Biol. 20, 1389–1399 (2018). This study demonstrates that TBK1 and IKKε phosphorylate RIPK1 to prevent TNF-induced RIPK1 kinase activity-dependent cell death.

Xu, D. et al. TBK1 suppresses RIPK1-driven apoptosis and inflammation during development and in aging. Cell 174, 1477–1491 (2018). This study demonstrates that TBK1 phosphorylates RIPK1 to prevent TNF-induced RIPK1 kinase activity-dependent cell death, and shows that inhibition of RIPK1 kinase activity rescues embryonic lethality of Tbk1-knockout mice.

Du, J. et al. RIPK1 dephosphorylation and kinase activation by PPP1R3G/PP1gamma promote apoptosis and necroptosis. Nat. Commun. 12, 7067 (2021).

Dondelinger, Y. et al. Serine 25 phosphorylation inhibits RIPK1 kinase-dependent cell death in models of infection and inflammation. Nat. Commun. 10, 1729 (2019).

Van Antwerp, D. J., Martin, S. J., Kafri, T., Green, D. R. & Verma, I. M. Suppression of TNF-alpha-induced apoptosis by NF-kappaB. Science 274, 787–789 (1996). This study provides the first description of the NF-κB-dependent checkpoint, demonstrating that TNF-induced NF-κB activation suppresses cell death.

Bertrand, M. J. et al. cIAP1 and cIAP2 facilitate cancer cell survival by functioning as E3 ligases that promote RIP1 ubiquitination. Mol. Cell 30, 689–700 (2008).

Vince, J. E. et al. IAP antagonists target cIAP1 to induce TNFalpha-dependent apoptosis. Cell 131, 682–693 (2007).

Moulin, M. et al. IAPs limit activation of RIP kinases by TNF receptor 1 during development. EMBO J. 31, 1679–1691 (2012).

Mahoney, D. J. et al. Both cIAP1 and cIAP2 regulate TNFalpha-mediated NF-kappaB activation. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 105, 11778–11783 (2008).

Taraborrelli, L. et al. LUBAC prevents lethal dermatitis by inhibiting cell death induced by TNF, TRAIL and CD95L. Nat. Commun. 9, 3910 (2018).

Peltzer, N. et al. LUBAC is essential for embryogenesis by preventing cell death and enabling haematopoiesis. Nature 557, 112–117 (2018).

Rickard, J. A. et al. TNFR1-dependent cell death drives inflammation in Sharpin-deficient mice. Elife 3, e03464 (2014).

Peltzer, N. et al. HOIP deficiency causes embryonic lethality by aberrant TNFR1-mediated endothelial cell death. Cell Rep. 9, 153–165 (2014).

O’Donnell, M. A., Legarda-Addison, D., Skountzos, P., Yeh, W. C. & Ting, A. T. Ubiquitination of RIP1 regulates an NF-kappaB-independent cell-death switch in TNF signaling. Curr. Biol. 17, 418–424 (2007). This study provides the first description of an NF-κB-independent checkpoint, demonstrating that ubiquitylation of RIPK1 on lysine 377 inhibits TNF-induced apoptosis.

Zhang, X. et al. Ubiquitination of RIPK1 suppresses programmed cell death by regulating RIPK1 kinase activation during embryogenesis. Nat. Commun. 10, 4158 (2019).

Tang, Y. et al. K63-linked ubiquitination regulates RIPK1 kinase activity to prevent cell death during embryogenesis and inflammation. Nat. Commun. 10, 4157 (2019).

Draber, P. et al. LUBAC-recruited CYLD and A20 regulate gene activation and cell death by exerting opposing effects on linear ubiquitin in signaling complexes. Cell Rep. 13, 2258–2272 (2015).

Priem, D. et al. A20 protects cells from TNF-induced apoptosis through linear ubiquitin-dependent and -independent mechanisms. Cell Death Dis. 10, 692 (2019).

Wertz, I. E. et al. Phosphorylation and linear ubiquitin direct A20 inhibition of inflammation. Nature 528, 370–375 (2015).

Polykratis, A. et al. A20 prevents inflammasome-dependent arthritis by inhibiting macrophage necroptosis through its ZnF7 ubiquitin-binding domain. Nat. Cell Biol. 21, 731–742 (2019).

Martens, A. et al. Two distinct ubiquitin-binding motifs in A20 mediate its anti-inflammatory and cell-protective activities. Nat. Immunol. 21, 381–387 (2020).

Heger, K. et al. OTULIN limits cell death and inflammation by deubiquitinating LUBAC. Nature 559, 120–124 (2018).

Lin, Y., Devin, A., Rodriguez, Y. & Liu, Z. G. Cleavage of the death domain kinase RIP by caspase-8 prompts TNF-induced apoptosis. Genes Dev. 13, 2514–2526 (1999).

Newton, K. et al. Cleavage of RIPK1 by caspase-8 is crucial for limiting apoptosis and necroptosis. Nature 574, 428–431 (2019).

Lalaoui, N. et al. Mutations that prevent caspase cleavage of RIPK1 cause autoinflammatory disease. Nature 577, 103–108 (2020).

Tao, P. et al. A dominant autoinflammatory disease caused by non-cleavable variants of RIPK1. Nature 577, 109–114 (2020). Lalaoui et al. (2020) and Tao et al. (2020) are the first reports of patients with autoinflammatory disease caused by mutation in RIPK1 specifically inactivating the caspase 8 checkpoint.

Zhang, X., Dowling, J. P. & Zhang, J. RIPK1 can mediate apoptosis in addition to necroptosis during embryonic development. Cell Death Dis. 10, 245 (2019). Newton et al. (2019) Lalaoui et al. (2020), Tao et al. (2020) and Zhang et al. (Cell Death Dis., 2019) provide an in vivo demonstration that the caspase 8 checkpoint consists of cleavage of RIPK1 by caspase 8, and protects against inflammatory disease caused by RIPK1 kinase activity-dependent cell death.

Dondelinger, Y. et al. MK2 phosphorylation of RIPK1 regulates TNF-mediated cell death. Nat. Cell Biol. 19, 1237–1247 (2017).

Menon, M. B. et al. p38(MAPK)/MK2-dependent phosphorylation controls cytotoxic RIPK1 signalling in inflammation and infection. Nat. Cell Biol. 19, 1248–1259 (2017).

Jaco, I. et al. MK2 phosphorylates RIPK1 to prevent TNF-induced cell death. Mol. Cell 66, 698–710 (2017).

Wu, W. et al. The autophagy-initiating kinase ULK1 controls RIPK1-mediated cell death. Cell Rep. 31, 107547 (2020).

Liu, L. et al. Tankyrase-mediated ADP-ribosylation is a regulator of TNF-induced death. Sci. Adv. 8, eabh2332 (2022).

Mukherjee, S. et al. Yersinia YopJ acetylates and inhibits kinase activation by blocking phosphorylation. Science 312, 1211–1214 (2006).

Mittal, R., Peak-Chew, S. Y. & McMahon, H. T. Acetylation of MEK2 and I kappa B kinase (IKK) activation loop residues by YopJ inhibits signaling. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 103, 18574–18579 (2006).

Haase, R., Richter, K., Pfaffinger, G., Courtois, G. & Ruckdeschel, K. Yersinia outer protein P suppresses TGF-beta-activated kinase-1 activity to impair innate immune signaling in Yersinia enterocolitica-infected cells. J. Immunol. 175, 8209–8217 (2005).

Paquette, N. et al. Serine/threonine acetylation of TGFbeta-activated kinase (TAK1) by Yersinia pestis YopJ inhibits innate immune signaling. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 109, 12710–12715 (2012).

Peterson, L. W. et al. RIPK1-dependent apoptosis bypasses pathogen blockade of innate signaling to promote immune defense. J. Exp. Med. 214, 3171–3182 (2017).

Peterson, L. W. et al. Cell-extrinsic TNF collaborates with TRIF signaling to promote yersinia-induced apoptosis. J. Immunol. 197, 4110–4117 (2016). Peterson et al. (2017) and Peterson et al. (2016) demonstrate that RIPK1 kinase activity-dependent cell death serves as a backup mechanism to promote immune defence against pathogens that have highjacked innate signalling.

Sarhan, J. et al. Caspase-8 induces cleavage of gasdermin D to elicit pyroptosis during Yersinia infection. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 115, 10888–10897 (2018).

Tummers, B. & Green, D. R. The evolution of regulated cell death pathways in animals and their evasion by pathogens. Physiol. Rev. 102, 411–454 (2022).

Zhou, Q. et al. Target protease specificity of the viral serpin CrmA. Analysis of five caspases. J. Biol. Chem. 272, 7797–7800 (1997).

Thome, M. et al. Viral FLICE-inhibitory proteins (FLIPs) prevent apoptosis induced by death receptors. Nature 386, 517–521 (1997).

Bertin, J. et al. Death effector domain-containing herpesvirus and poxvirus proteins inhibit both Fas- and TNFR1-induced apoptosis. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 94, 1172–1176 (1997).

Karki, R. et al. Synergism of TNF-alpha and IFN-gamma triggers inflammatory cell death, tissue damage, and mortality in SARS-CoV-2 infection and cytokine shock syndromes. Cell 184, 149–168 (2021).

Roca, F. J., Whitworth, L. J., Redmond, S., Jones, A. A. & Ramakrishnan, L. TNF induces pathogenic programmed macrophage necrosis in tuberculosis through a mitochondrial-lysosomal-endoplasmic reticulum circuit. Cell 178, 1344–1361 (2019).

Van Hauwermeiren, F. et al. Bacillus anthracis induces NLRP3 inflammasome activation and caspase-8-mediated apoptosis of macrophages to promote lethal anthrax. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.2116415119 (2022).

Simpson, D. S. et al. Interferon-gamma primes macrophages for pathogen ligand-induced killing via a caspase-8 and mitochondrial cell death pathway. Immunity 55, 423–441 (2022).

Duprez, L. et al. RIP kinase-dependent necrosis drives lethal systemic inflammatory response syndrome. Immunity 35, 908–918 (2011). This study provides the first demonstration that RIPK1 kinase activity-dependent cell death drives the inflammatory lethal shock caused by TNF injection in mice.

Newton, K. et al. Activity of protein kinase RIPK3 determines whether cells die by necroptosis or apoptosis. Science 343, 1357–1360 (2014).

Berger, S. B. et al. Cutting edge: RIP1 kinase activity is dispensable for normal development but is a key regulator of inflammation in SHARPIN-deficient mice. J. Immunol. 192, 5476–5480 (2014).

Newton, K. et al. RIPK3 deficiency or catalytically inactive RIPK1 provides greater benefit than MLKL deficiency in mouse models of inflammation and tissue injury. Cell Death Differ. 23, 1565–1576 (2016).

Varfolomeev, E. et al. Cellular inhibitors of apoptosis are global regulators of NF-kappaB and MAPK activation by members of the TNF family of receptors. Sci. Signal. 5, ra22 (2012).

Vince, J. E. et al. TWEAK-FN14 signaling induces lysosomal degradation of a cIAP1-TRAF2 complex to sensitize tumor cells to TNFalpha. J. Cell Biol. 182, 171–184 (2008).

Croft, M. & Siegel, R. M. Beyond TNF: TNF superfamily cytokines as targets for the treatment of rheumatic diseases. Nat. Rev. Rheumatol. 13, 217–233 (2017).

Kawashima, R. et al. Interleukin-13 damages intestinal mucosa via TWEAK and Fn14 in mice-a pathway associated with ulcerative colitis. Gastroenterology 141, 2119–2129 (2011).

Lucas, C. et al. Longitudinal analyses reveal immunological misfiring in severe COVID-19. Nature 584, 463–469 (2020).

Rodrigues, T. S. et al. Inflammasomes are activated in response to SARS-CoV-2 infection and are associated with COVID-19 severity in patients. J. Exp. Med. 218, e20201707 (2021).

Ferreira, A. C. et al. SARS-CoV-2 engages inflammasome and pyroptosis in human primary monocytes. Cell Death Discov. 7, 43 (2021).

Varfolomeev, E. E. et al. Targeted disruption of the mouse caspase 8 gene ablates cell death induction by the TNF receptors, Fas/Apo1, and DR3 and is lethal prenatally. Immunity 9, 267–276 (1998).

Zhang, J., Cado, D., Chen, A., Kabra, N. H. & Winoto, A. Fas-mediated apoptosis and activation-induced T-cell proliferation are defective in mice lacking FADD/Mort1. Nature 392, 296–300 (1998).

Kaiser, W. J. et al. RIP3 mediates the embryonic lethality of caspase-8-deficient mice. Nature 471, 368–372 (2011).

Oberst, A. et al. Catalytic activity of the caspase-8-FLIP(L) complex inhibits RIPK3-dependent necrosis. Nature 471, 363–367 (2011).

Zhang, H. et al. Functional complementation between FADD and RIP1 in embryos and lymphocytes. Nature 471, 373–376 (2011). Kaiser et al. (2011), Oberst et al. (2011) and Zhang et al. (2011) provide the first in vivo evidence of the caspase 8 checkpoint, demonstrating that caspase 8 is essential to prevent RIPK3-dependent necroptosis during embryonic development.

Alvarez-Diaz, S. et al. The pseudokinase MLKL and the kinase RIPK3 have distinct roles in autoimmune disease caused by loss of death-receptor-induced apoptosis. Immunity 45, 513–526 (2016).

Welz, P. S. et al. FADD prevents RIP3-mediated epithelial cell necrosis and chronic intestinal inflammation. Nature 477, 330–334 (2011).

Gunther, C. et al. Caspase-8 regulates TNF-alpha-induced epithelial necroptosis and terminal ileitis. Nature 477, 335–339 (2011). Welz et al. (2011) and Gunther et al. (2011) provide the first in vivo evidence of the caspase 8 checkpoint, demonstrating that caspase 8 is essential to prevent RIPK3-dependent IEC necroptosis and intestinal inflammation.

Weinlich, R. et al. Protective roles for caspase-8 and cFLIP in adult homeostasis. Cell Rep. 5, 340–348 (2013).

Lehle, A. S. et al. Intestinal inflammation and dysregulated immunity in patients with inherited caspase-8 deficiency. Gastroenterology 156, 275–278 (2019).

Chun, H. J. et al. Pleiotropic defects in lymphocyte activation caused by caspase-8 mutations lead to human immunodeficiency. Nature 419, 395–399 (2002).

Bader, S. M. et al. Endothelial caspase-8 prevents fatal necroptotic hemorrhage caused by commensal bacteria. Cell Death Differ. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41418-022-01042-8 (2022).

Kovalenko, A. et al. Caspase-8 deficiency in epidermal keratinocytes triggers an inflammatory skin disease. J. Exp. Med. 206, 2161–2177 (2009).

Bonnet, M. C. et al. The adaptor protein FADD protects epidermal keratinocytes from necroptosis in vivo and prevents skin inflammation. Immunity 35, 572–582 (2011). This study provides the first in vivo evidence of the caspase 8 checkpoint, demonstrating that caspase 8 is essential to prevent RIPK3-dependent keratinocyte necroptosis and skin inflammation.

Dondelinger, Y. et al. RIPK3 contributes to TNFR1-mediated RIPK1 kinase-dependent apoptosis in conditions of cIAP1/2 depletion or TAK1 kinase inhibition. Cell Death Differ. 20, 1381–1392 (2013). This article shows that RIPK1 kinase activity is not restricted to necroptosis but also drives apoptosis downstream of TNFR1.

Dannappel, M. et al. RIPK1 maintains epithelial homeostasis by inhibiting apoptosis and necroptosis. Nature 513, 90–94 (2014).

Devos, M. et al. Sensing of endogenous nucleic acids by ZBP1 induces keratinocyte necroptosis and skin inflammation. J. Exp. Med. 217, e20191913 (2020).

Tapiz, I. R. A. J. et al. Characterization of novel pathogenic variants leading to caspase-8 cleavage-resistant RIPK1-induced autoinflammatory syndrome. J. Clin. Immunol. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10875-022-01298-2 (2022).

Kupka, S., Reichert, M., Draber, P. & Walczak, H. Formation and removal of poly-ubiquitin chains in the regulation of tumor necrosis factor-induced gene activation and cell death. FEBS J. 283, 2626–2639 (2016).

Beck, D. B., Werner, A., Kastner, D. L. & Aksentijevich, I. Disorders of ubiquitylation: unchained inflammation. Nat. Rev. Rheumatol. 18, 435–447 (2022).

Zhang, J. et al. Ubiquitin ligases cIAP1 and cIAP2 limit cell death to prevent inflammation. Cell Rep. 27, 2679–2689 (2019).

Rigaud, S. et al. XIAP deficiency in humans causes an X-linked lymphoproliferative syndrome. Nature 444, 110–114 (2006).

Yabal, M. et al. XIAP restricts TNF- and RIP3-dependent cell death and inflammasome activation. Cell Rep. 7, 1796–1808 (2014).

Wahida, A. et al. XIAP restrains TNF-driven intestinal inflammation and dysbiosis by promoting innate immune responses of Paneth and dendritic cells. Sci. Immunol. 6, eabf7235 (2021).

Lawlor, K. E. et al. RIPK3 promotes cell death and NLRP3 inflammasome activation in the absence of MLKL. Nat. Commun. 6, 6282 (2015).

HogenEsch, H. et al. A spontaneous mutation characterized by chronic proliferative dermatitis in C57BL mice. Am. J. Pathol. 143, 972–982 (1993).

Gerlach, B. et al. Linear ubiquitination prevents inflammation and regulates immune signalling. Nature 471, 591–596 (2011).

Tokunaga, F. et al. SHARPIN is a component of the NF-kappaB-activating linear ubiquitin chain assembly complex. Nature 471, 633–636 (2011).

Ikeda, F. et al. SHARPIN forms a linear ubiquitin ligase complex regulating NF-kappaB activity and apoptosis. Nature 471, 637–641 (2011).

Kumari, S. et al. Sharpin prevents skin inflammation by inhibiting TNFR1-induced keratinocyte apoptosis. Elife 3, e03422 (2014).

Sharma, B. R. et al. Innate immune adaptor MyD88 deficiency prevents skin inflammation in SHARPIN-deficient mice. Cell Death Differ. 26, 741–750 (2019).

Hoste, E. et al. OTULIN maintains skin homeostasis by controlling keratinocyte death and stem cell identity. Nat. Commun. 12, 5913 (2021).

Schunke, H., Gobel, U., Dikic, I. & Pasparakis, M. OTULIN inhibits RIPK1-mediated keratinocyte necroptosis to prevent skin inflammation in mice. Nat. Commun. 12, 5912 (2021).

Boisson, B. et al. Human HOIP and LUBAC deficiency underlies autoinflammation, immunodeficiency, amylopectinosis, and lymphangiectasia. J. Exp. Med. 212, 939–951 (2015).

Boisson, B. et al. Immunodeficiency, autoinflammation and amylopectinosis in humans with inherited HOIL-1 and LUBAC deficiency. Nat. Immunol. 13, 1178–1186 (2012).

Oda, H. et al. Second case of HOIP deficiency expands clinical features and defines inflammatory transcriptome regulated by LUBAC. Front. Immunol. 10, 479 (2019).

Damgaard, R. B. et al. The deubiquitinase OTULIN is an essential negative regulator of inflammation and autoimmunity. Cell 166, 1215–1230 (2016).

Damgaard, R. B. et al. OTULIN deficiency in ORAS causes cell type-specific LUBAC degradation, dysregulated TNF signalling and cell death. EMBO Mol. Med. 11, e9324 (2019).

Zhou, Q. et al. Biallelic hypomorphic mutations in a linear deubiquitinase define otulipenia, an early-onset autoinflammatory disease. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 113, 10127–10132 (2016).

Nabavi, M. et al. Auto-inflammation in a patient with a novel homozygous OTULIN mutation. J. Clin. Immunol. 39, 138–141 (2019).

Zinngrebe, J. et al. Compound heterozygous variants in OTULIN are associated with fulminant atypical late-onset ORAS. EMBO Mol. Med. 14, e14901 (2022).

Lee, E. G. et al. Failure to regulate TNF-induced NF-kappaB and cell death responses in A20-deficient mice. Science 289, 2350–2354 (2000).

Vereecke, L. et al. Enterocyte-specific A20 deficiency sensitizes to tumor necrosis factor-induced toxicity and experimental colitis. J. Exp. Med. 207, 1513–1523 (2010).

Vereecke, L. et al. A20 controls intestinal homeostasis through cell-specific activities. Nat. Commun. 5, 5103 (2014).

Catrysse, L. et al. A20 prevents chronic liver inflammation and cancer by protecting hepatocytes from death. Cell Death Dis. 7, e2250 (2016).

Kattah, M. G. et al. A20 and ABIN-1 synergistically preserve intestinal epithelial cell survival. J. Exp. Med. 215, 1839–1852 (2018).

Slowicka, K. et al. Physical and functional interaction between A20 and ATG16L1-WD40 domain in the control of intestinal homeostasis. Nat. Commun. 10, 1834 (2019).

Vetters, J. et al. The ubiquitin-editing enzyme A20 controls NK cell homeostasis through regulation of mTOR activity and TNF. J. Exp. Med. 216, 2010–2023 (2019).

Razani, B. et al. Non-catalytic ubiquitin binding by A20 prevents psoriatic arthritis-like disease and inflammation. Nat. Immunol. 21, 422–433 (2020).

Martens, A. & van Loo, G. A20 at the crossroads of cell death, inflammation, and autoimmunity. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Biol. 12, a036418 (2019).

Priem, D., van Loo, G. & Bertrand, M. J. M. A20 and cell death-driven inflammation. Trends Immunol. 41, 421–435 (2020).

Aeschlimann, F. A. et al. A20 haploinsufficiency (HA20): clinical phenotypes and disease course of patients with a newly recognised NF-kB-mediated autoinflammatory disease. Ann. Rheum. Dis. 77, 728–735 (2018).

Zhou, Q. et al. Loss-of-function mutations in TNFAIP3 leading to A20 haploinsufficiency cause an early-onset autoinflammatory disease. Nat. Genet. 48, 67–73 (2016).

Zilberman-Rudenko, J. et al. Recruitment of A20 by the C-terminal domain of NEMO suppresses NF-kappaB activation and autoinflammatory disease. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 113, 1612–1617 (2016).

Li, Z. W. et al. The IKKbeta subunit of IkappaB kinase (IKK) is essential for nuclear factor kappaB activation and prevention of apoptosis. J. Exp. Med. 189, 1839–1845 (1999).

Li, Q., Estepa, G., Memet, S., Israel, A. & Verma, I. M. Complete lack of NF-kappaB activity in IKK1 and IKK2 double-deficient mice: additional defect in neurulation. Genes Dev. 14, 1729–1733 (2000).

Rudolph, D. et al. Severe liver degeneration and lack of NF-kappaB activation in NEMO/IKKgamma-deficient mice. Genes Dev. 14, 854–862 (2000).

Takeda, K. et al. Limb and skin abnormalities in mice lacking IKKalpha. Science 284, 313–316 (1999).

Makris, C. et al. Female mice heterozygous for IKK gamma/NEMO deficiencies develop a dermatopathy similar to the human X-linked disorder incontinentia pigmenti. Mol. Cell 5, 969–979 (2000).

Schmidt-Supprian, M. et al. NEMO/IKK gamma-deficient mice model incontinentia pigmenti. Mol. Cell 5, 981–992 (2000).

Nenci, A. et al. Skin lesion development in a mouse model of incontinentia pigmenti is triggered by NEMO deficiency in epidermal keratinocytes and requires TNF signaling. Hum. Mol. Genet. 15, 531–542 (2006).

Smahi, A. et al. Genomic rearrangement in NEMO impairs NF-kappaB activation and is a cause of incontinentia pigmenti. The International Incontinentia Pigmenti (IP) Consortium. Nature 405, 466–472 (2000).

Lee, Y. et al. Genetically programmed alternative splicing of NEMO mediates an autoinflammatory disease phenotype. J. Clin. Invest. 132, e128808 (2022).

de Jesus, A. A. et al. Distinct interferon signatures and cytokine patterns define additional systemic autoinflammatory diseases. J. Clin. Invest. 130, 1669–1682 (2020).

Pasparakis, M. et al. TNF-mediated inflammatory skin disease in mice with epidermis-specific deletion of IKK2. Nature 417, 861–866 (2002).

Kumari, S. et al. NF-kappaB inhibition in keratinocytes causes RIPK1-mediated necroptosis and skin inflammation. Life Sci. Alliance 4, e202000956 (2021).

Badran, Y. R. et al. Human RELA haploinsufficiency results in autosomal-dominant chronic mucocutaneous ulceration. J. Exp. Med. 214, 1937–1947 (2017).

Nenci, A. et al. Epithelial NEMO links innate immunity to chronic intestinal inflammation. Nature 446, 557–561 (2007).

Vlantis, K. et al. NEMO prevents RIP kinase 1-mediated epithelial cell death and chronic intestinal inflammation by NF-kappaB-dependent and -independent functions. Immunity 44, 553–567 (2016).

Bonnard, M. et al. Deficiency of T2K leads to apoptotic liver degeneration and impaired NF-kappaB-dependent gene transcription. EMBO J. 19, 4976–4985 (2000).

Marchlik, E. et al. Mice lacking Tbk1 activity exhibit immune cell infiltrates in multiple tissues and increased susceptibility to LPS-induced lethality. J. Leukoc. Biol. 88, 1171–1180 (2010).

Taft, J. et al. Human TBK1 deficiency leads to autoinflammation driven by TNF-induced cell death. Cell 184, 4447–4463 (2021). This study describes patients with TBK1 deficiency (affecting the IKK checkpoint) developing autoinflammation caused by TNF-induced cell death.

Yeh, W. C. et al. Requirement for Casper (c-FLIP) in regulation of death receptor-induced apoptosis and embryonic development. Immunity 12, 633–642 (2000).

Dillon, C. P. et al. Survival function of the FADD-CASPASE-8-cFLIP(L) complex. Cell Rep. 1, 401–407 (2012).

Piao, X. et al. c-FLIP maintains tissue homeostasis by preventing apoptosis and programmed necrosis. Sci. Signal. 5, ra93 (2012).

Wittkopf, N. et al. Cellular FLICE-like inhibitory protein secures intestinal epithelial cell survival and immune homeostasis by regulating caspase-8. Gastroenterology 145, 1369–1379 (2013).

Panayotova-Dimitrova, D. et al. cFLIP regulates skin homeostasis and protects against TNF-induced keratinocyte apoptosis. Cell Rep. 5, 397–408 (2013).

Dillon, C. P. et al. RIPK1 blocks early postnatal lethality mediated by caspase-8 and RIPK3. Cell 157, 1189–1202 (2014).

Rickard, J. A. et al. RIPK1 regulates RIPK3-MLKL-driven systemic inflammation and emergency hematopoiesis. Cell 157, 1175–1188 (2014).

Kaiser, W. J. et al. RIP1 suppresses innate immune necrotic as well as apoptotic cell death during mammalian parturition. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 111, 7753–7758 (2014).

Takahashi, N. et al. RIPK1 ensures intestinal homeostasis by protecting the epithelium against apoptosis. Nature 513, 95–99 (2014).

Gentle, I. E. et al. In TNF-stimulated cells, RIPK1 promotes cell survival by stabilizing TRAF2 and cIAP1, which limits induction of non-canonical NF-kappaB and activation of caspase-8. J. Biol. Chem. 286, 13282–13291 (2011).

Cuchet-Lourenco, D. et al. Biallelic RIPK1 mutations in humans cause severe immunodeficiency, arthritis, and intestinal inflammation. Science 361, 810–813 (2018). This study describes patients with RIPK1 deficiency developing immunodeficiency with autoinflammatory pathologies.

Li, Y. et al. Human RIPK1 deficiency causes combined immunodeficiency and inflammatory bowel diseases. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 116, 970–975 (2019).

Silva-Fernandez, L. & Hyrich, K. Rheumatoid arthritis: when TNF inhibitors fail in RA-weighing up the options. Nat. Rev. Rheumatol. 10, 262–264 (2014).

Roda, G., Jharap, B., Neeraj, N. & Colombel, J. F. Loss of response to anti-TNFs: definition, epidemiology, and management. Clin. Transl. Gastroenterol. 7, e135 (2016).

Esposito, M. et al. Survival rate of antitumour necrosis factor-alpha treatments for psoriasis in routine dermatological practice: a multicentre observational study. Br. J. Dermatol. 169, 666–672 (2013).

Degterev, A. et al. Identification of RIP1 kinase as a specific cellular target of necrostatins. Nat. Chem. Biol. 4, 313–321 (2008).

Xie, T. et al. Structural basis of RIP1 inhibition by necrostatins. Structure 21, 493–499 (2013).

Weisel, K. et al. A randomized, placebo-controlled experimental medicine study of RIPK1 inhibitor GSK2982772 in patients with moderate to severe rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Res. Ther. 23, 85 (2021).

Weisel, K. et al. A randomised, placebo-controlled study of RIPK1 inhibitor GSK2982772 in patients with active ulcerative colitis. BMJ Open Gastroenterol. 8, e000680 (2021).

Mandal, P. et al. RIP3 induces apoptosis independent of pronecrotic kinase activity. Mol. Cell 56, 481–495 (2014).

Shi, J. et al. Cleavage of GSDMD by inflammatory caspases determines pyroptotic cell death. Nature 526, 660–665 (2015).

Kayagaki, N. et al. Caspase-11 cleaves gasdermin D for non-canonical inflammasome signalling. Nature 526, 666–671 (2015). Shi et al. (2015) and Kayagaki et al. (2015) identify GSDMD as the substrate cleaved by caspase 11 to mediate pyroptosis.

Liu, X., Xia, S., Zhang, Z., Wu, H. & Lieberman, J. Channelling inflammation: gasdermins in physiology and disease. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 20, 384–405 (2021).

Hu, J. J. et al. FDA-approved disulfiram inhibits pyroptosis by blocking gasdermin D pore formation. Nat. Immunol. 21, 736–745 (2020).

Li, S. et al. Gasdermin D in peripheral myeloid cells drives neuroinflammation in experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis. J. Exp. Med. 216, 2562–2581 (2019).

Rathkey, J. K. et al. Chemical disruption of the pyroptotic pore-forming protein gasdermin D inhibits inflammatory cell death and sepsis. Sci. Immunol. 3, eaat2738 (2018).

Humphries, F. et al. Succination inactivates gasdermin D and blocks pyroptosis. Science 369, 1633–1637 (2020).

Rogers, C. et al. Cleavage of DFNA5 by caspase-3 during apoptosis mediates progression to secondary necrotic/pyroptotic cell death. Nat. Commun. 8, 14128 (2017).

Wang, Y. et al. Chemotherapy drugs induce pyroptosis through caspase-3 cleavage of a gasdermin. Nature 547, 99–103 (2017).

Hou, J. et al. PD-L1-mediated gasdermin C expression switches apoptosis to pyroptosis in cancer cells and facilitates tumour necrosis. Nat. Cell Biol. 22, 1264–1275 (2020).

Kayagaki, N. et al. NINJ1 mediates plasma membrane rupture during lytic cell death. Nature 591, 131–136 (2021).

Kerr, J. F., Wyllie, A. H. & Currie, A. R. Apoptosis: a basic biological phenomenon with wide-ranging implications in tissue kinetics. Br. J. Cancer 26, 239–257 (1972).

Holler, N. et al. Fas triggers an alternative, caspase-8-independent cell death pathway using the kinase RIP as effector molecule. Nat. Immunol. 1, 489–495 (2000).

Zhang, D. W. et al. RIP3, an energy metabolism regulator that switches TNF-induced cell death from apoptosis to necrosis. Science 325, 332–336 (2009).

Cho, Y. S. et al. Phosphorylation-driven assembly of the RIP1-RIP3 complex regulates programmed necrosis and virus-induced inflammation. Cell 137, 1112–1123 (2009).

He, S. et al. Receptor interacting protein kinase-3 determines cellular necrotic response to TNF-alpha. Cell 137, 1100–1111 (2009). Zhang et al. (2009), Cho et al. (2009) and He et al. (2009) identify RIPK3 as crucial effector of TNF-induced necroptosis.

Sun, L. et al. Mixed lineage kinase domain-like protein mediates necrosis signaling downstream of RIP3 kinase. Cell 148, 213–227 (2012). This study identifies MLKL as the most downstream crucial effector of TNF-induced necroptosis.

Brennan, F. M., Chantry, D., Jackson, A., Maini, R. & Feldmann, M. Inhibitory effect of TNF alpha antibodies on synovial cell interleukin-1 production in rheumatoid arthritis. Lancet 2, 244–247 (1989).

Haworth, C. et al. Expression of granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor in rheumatoid arthritis: regulation by tumor necrosis factor-alpha. Eur. J. Immunol. 21, 2575–2579 (1991).

Williams, R. O., Feldmann, M. & Maini, R. N. Anti-tumor necrosis factor ameliorates joint disease in murine collagen-induced arthritis. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 89, 9784–9788 (1992).

Elliott, M. J. et al. Treatment of rheumatoid arthritis with chimeric monoclonal antibodies to tumor necrosis factor alpha. Arthritis Rheum. 36, 1681–1690 (1993). This is the first clinical study with anti-TNF antibodies showing clinical improvement in most patients with rheumatoid arthritis.

Elliott, M. J. et al. Randomised double-blind comparison of chimeric monoclonal antibody to tumour necrosis factor alpha (cA2) versus placebo in rheumatoid arthritis. Lancet 344, 1105–1110 (1994).

Elliott, M. J. et al. Repeated therapy with monoclonal antibody to tumour necrosis factor alpha (cA2) in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Lancet 344, 1125–1127 (1994).

Lipsky, P. E. et al. Infliximab and methotrexate in the treatment of rheumatoid arthritis. N. Engl. J. Med. 343, 1594–1602 (2000).

Feldmann, M. & Maini, R. N. Lasker Clinical Medical Research Award. TNF defined as a therapeutic target for rheumatoid arthritis and other autoimmune diseases. Nat. Med. 9, 1245–1250 (2003).

Croft, M., Benedict, C. A. & Ware, C. F. Clinical targeting of the TNF and TNFR superfamilies. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 12, 147–168 (2013).

Acknowledgements

The G.v.L. laboratory is supported by the Vlaams Instituut voor Biotechnologie, by Ghent University (BOF) and by grants from the Fonds voor Wetenschappelijk Onderzoek Vlaanderen (G090322N, G026520N, G012618N and EOS-G0H2522N), the Charcot Foundation, the Belgian Foundation against Cancer and the FOREUM Foundation for Research in Rheumatology. Research in the laboratory of M.J.M.B. is supported by the Vlaams Instituut voor Biotechnologie, by Ghent University (iBOF ATLANTIS) and by grants from the Fonds voor Wetenschappelijk Onderzoek Vlaanderen (G035320N, G044518N, EOS G0G6618N and EOS G0I5722N) and the Flemish Government (Methusalem BOF16/MET_V/007 to P. Vandenabeele).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

The authors contributed equally to all aspects of the article.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Reviews Immunology thanks I. Aksentijevich and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Related links

OMIM: www.omim.org

Glossary

- Necroptosis

-

A programmed form of necrosis whose execution relies on the activation of receptor-interacting serine/threonine protein kinase 3 (RIPK3) and subsequent phosphorylation of mixed lineage kinase domain-like protein (MLKL) by RIPK3, ultimately leading to the translocation of phosphorylated MLKL to the plasma membrane, where it either directly or indirectly causes plasma membrane rupture.

- Pyroptosis

-

A highly inflammatory form of programmed necrosis, usually caused by microbial infection, that relies on the proteolytic activation of the pore-forming molecule gasdermin D by caspase 1 and caspase 11 (or caspase 8). It is classically activated downstream of the inflammasome pathways and is associated with the release of biologically active IL-1β and IL-18.

- Secondary necrosis

-

A lytic, or necrotic, form of cell death that occurs when apoptotic cells are not efficiently removed by efferocytosis. It involves proteolytic activation of the pore-forming molecule gasdermin E by the effector caspase 3.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

van Loo, G., Bertrand, M.J.M. Death by TNF: a road to inflammation. Nat Rev Immunol 23, 289–303 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41577-022-00792-3

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

Issue date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41577-022-00792-3

This article is cited by

-

Investigation of the anti-inflammatory effects of photobiomodulation therapy on human gingival fibroblasts (HGF1-PI1)

Molecular Biology Reports (2026)

-

Phage receptor binding protein and Fc fragment fusion enhances phagocytosis of Y. enterocolitica

AMB Express (2025)

-

Puerarin esters mitigate oxygen and glucose deprivation-reoxygenation-induced injury in microglial cells

Food Production, Processing and Nutrition (2025)

-

Exploring the association between rheumatoid arthritis and non-small cell lung cancer risk: a transcriptomic and drug target-based analysis

Hereditas (2025)

-

Unraveling the complexities of diet induced obesity and glucolipid dysfunction in metabolic syndrome

Diabetology & Metabolic Syndrome (2025)