SUMMARY

Receptor interacting protein kinase (RIPK)-1 is involved in RIPK3-dependent and independent signaling pathways leading to cell death and/or inflammation. Genetic ablation of RIPK1 causes postnatal lethality, which was not prevented by deletion of RIPK3, caspase-8 or FADD. However, animals that lack RIPK1, RIPK3, and either caspase-8 or FADD survived weaning and matured normally. RIPK1 functions in vitro to limit caspase-8-dependent, TNFR-induced apoptosis and animals lacking RIPK1, RIPK3, and TNFR1 survive to adulthood. The role of RIPK3 in promoting lethality in ripk1−/− mice suggests that RIPK3 activation is inhibited by RIPK1 post-birth. While TNFR-induced RIPK3-dependent necroptosis requires RIPK1, cells lacking RIPK1 were sensitized to necroptosis triggered by poly I:C or interferons. Disruption of TLR (TRIF) or type I interferon (IFNAR) signaling delayed lethality in ripk1−/− tnfr1−/− mice. These results clarify the complex roles for RIPK1 in postnatal life and provide insights into the regulation of FADD-caspase-8 and RIPK3-MLKL signaling by RIPK1.

INTRODUCTION

RIPK1 is a kinase with several roles in signaling by TNFR1 (Biton and Ashkenazi, 2011; Cusson et al., 2002; Kelliher et al., 1998; Vandenabeele et al., 2010; Zhang et al., 2000), Toll-like receptors (TLRs) (Festjens et al., 2007; Kaiser et al., 2013; Meylan et al., 2004), interferons (Meylan et al., 2004; Thapa et al., 2013), the RIG-I-MAVS pathway (Rajput et al., 2011) and production of IL1α in SHP1-deficient animals (Lukens et al., 2013). Upon activation, it associates with RIPK3 to form a beta-amyloid (Li et al., 2012), promoting necroptosis and inflammatory cytokine production, dependent on the pseudokinase, MLKL (Kang et al., 2013; Murphy et al., 2013). In its kinase active form, it also recruits the adapter molecule, FADD, which in turn activates caspase-8 to promote apoptosis induced by TLR signaling or DNA damage (Tenev et al., 2011; Wang et al., 2008). These activities of RIPK1 are effectively blocked by necrostatins, including necrostatin-1 (Nec1) (Degterev et al., 2008), which act to inhibit the kinase function. Independent of its kinase activity, RIPK1 appears to participate in NF-κB activation through the recruitment of NEMO (Micheau et al., 2001; Wang et al., 2008; Zhang et al., 2000), although its requirement for NF-κB activation in response to TNFR1 ligation is controversial (Wong et al., 2010). Nevertheless, the activation of NF-κB induces the expression of c-FLIPL (FLIP), a caspase-like molecule that forms a heterodimer with caspase-8 on FADD and blocks FADD-caspase-8-mediated apoptosis (Micheau et al., 2001; Wang et al., 2008).

The FADD-caspase-8-FLIP complex functions to inhibit RIPK3 activation, blocking necroptosis. Indeed, early embryonic lethality of fadd−/− or casp8−/− animals is rescued by ablation of ripk3 (Dillon et al., 2012; Kaiser et al., 2011; Oberst et al., 2011), and a similar lethality of FLIP-deficient (cflar−/−) mice is rescued by ablation of both fadd and ripk3 (Dillon et al., 2012). Together, these findings provided what appeared to be a complete picture of the interactions of FADD-caspase-8-FLIP and the RIPK1-RIPK3-MLKL complexes in the control of cell death (Green et al., 2011).

A fundamental paradox emerged, however, when the function of RIPK1 was interrogated by genetic approaches. While the embryonic lethality of fadd−/− mice was rescued by ablation of ripk1, these animals died around postnatal day 1 (Zhang et al., 2011), as had been observed for ripk1−/− mice (Kelliher et al., 1998). But if RIPK1 were required for the activation of RIPK3, as discussed above, then fadd−/− ripk1−/− animals should have survived to adulthood, as do fadd−/− ripk3−/− mice (Dillon et al., 2012). The postnatal lethality of ripk1−/− animals was therefore most easily explained as due to the loss of another function of RIPK1, requisite for postnatal survival. For example, RIPK1 has been suggested to regulate the induction of NF-κB by recruitment of NEMO (Zhang et al., 2000). Perturbation of the NF-κB pathway by ablation of RIPK1 might then trigger the non-canonical NF-κB2, as is observed upon deletion of other elements of the canonical NF-κB pathway (Varfolomeev et al., 2007; Vince et al., 2007).

An alternative to this explanation, however, is that RIPK1 functions to inhibit both FADD-caspase-8-mediated apoptosis and RIPK3-mediated necroptosis, both triggered by signals generated around the time of birth. This idea stands in striking contrast to the widespread notion that RIPK1, in its kinase-active form, initiates both FADD-caspase-8 mediated apoptosis (Feoktistova et al., 2011; Tenev et al., 2011), and RIPK3 activation to cause necroptosis (Cho et al., 2009; Holler et al., 2000). However, both caspase-8 (Wang et al., 2008) and RIPK3 (Kaiser et al., 2013; Moujalled et al., 2013; Upton et al., 2012) can be activated in the absence of RIPK1 in some settings, resulting in different forms of cell death. If RIPK1 can block cell death in these settings, then this might explain why its ablation leads to lethality. Here, we test these ideas by several approaches.

RESULTS

Perinatal lethality of ripk1/− mice is dependent on caspase-8 and RIPK3

To test the possibility that perinatal lethality in the ripk1−/− mouse is due to over-activation of NF-κB2, we generated mice lacking both RIPK1 and the NF-κB2-activator, NIK. Like RIPK1, NIK is regulated by c-IAP1 and c-IAP2 (Varfolomeev et al., 2007; Vince et al., 2007). Further, TRAF2 or TRAF3 ablation cause perinatal lethality that is prevented on a background lacking NIK (Vallabhapurapu et al., 2008). Nevertheless, we found that ripk1−/− nik−/− mice did not display any improved survival versus animals lacking RIPK1 alone, and no animals survived to weaning (Fig. S1A). Therefore, the perinatal lethality caused by loss of RIPK1 is not due to enhanced activity of NIK.

We therefore tested the notion that RIPK1 functions to inhibit two modes of cell death, such that ablation of this protein results in lethality. While we found that postnatal lethality of ripk1−/− mice was, at best, only marginally affected by ablation of ripk3 (Fig. 1A, S1B,C), and unaffected by ablation of casp8 (Fig. 1A, S1D,E), animals lacking ripk1, ripk3, and casp8 survived into adulthood (Fig. 1A, S1F–G) and were weaned at Mendelian frequencies (Fig. 1B). Similarly, while fadd−/− ripk1−/− mice do not survive the first days of postnatal life (Zhang et al., 2011), mice lacking ripk1, ripk3, and fadd were weaned at expected frequencies (Fig. 1C). Ripk1−/− ripk3−/− casp8−/− and ripk1−/− ripk3−/− fadd−/− mice gained weight over time and appeared similar to their littermates for several months (Fig. 1D–G). Formally, then, the ripk1 gene inhibits perinatal lethality dependent on ripk3 and either casp8 or fadd.

Figure 1. Lethality of ripk1−/− mice is rescued by concomitant ablation of ripk3 and caspase-8 or fadd.

(A) Compilation of pup survival of the given genotypes from various crosses. See Figure S1B,D,F for survival data from the individual crosses. The numbers in brackets refer to the number of individual pups of each genotype.

(B) Expected and observed frequency of genotypes in offspring at weaning from crosses of ripk1+/− ripk3−/− casp8−/− and ripk1+/− ripk3−/− casp8+/− mice (p=0.8465 for comparison of ripk1 status among ripk3−/− casp8−/− genotypes).

(C) Expected and observed frequency of genotypes in offspring at weaning from crosses of ripk1+/− ripk3−/− fadd−/− and ripk1+/− ripk3−/− fadd+/− mice (p=0.9592 for comparison of ripk1 status among ripk3−/− fadd−/− genotypes).

(D) Weight vs. age of male ripk1−/− ripk3−/− casp8−/− or control littermates (p=0.8539).

(E) 5-week old ripk1−/− ripk3−/− casp8−/− mouse (arrow) and littermate control.

(F) 5-week old ripk1−/− ripk3−/− fadd−/− mouse (arrow) and littermate control.

(G) As in (D), but for ripk1−/− ripk3−/− fadd−/− males or control littermates (p=0.2787). See also Figure S1.

Ripk3−/− casp8−/− mice eventually display acute lymphoproliferative syndrome (ALPS), normally associated with defects in CD95 signaling (Kaiser et al., 2011; Oberst et al., 2011). Similarly, ripk1−/− ripk3−/− casp8−/− animals matured normally (Fig. 1D,E) and displayed ALPS after several months (Fig. 2A), with expansion of the CD3+B220+ lymphocyte subset associated with ALPS (Bidere et al., 2006) (Fig. 2B,C). ALPS was also observed in ripk3−/− fadd−/− mice (Dillon, et al., 2012) and the expansion of the aberrant lymphocyte subset was similarly seen in ripk1−/− ripk3−/− fadd−/− mice (Fig. 2D). Naïve T cells from young ripk1−/− ripk3−/− casp8−/− animals were present in normal proportions (Fig. 2E) and were activated similarly to WT T cells in response to CD3, CD28 ligation (Fig. 2F). Therefore, RIPK1 is not required for in vitro T cell activation, or for the expansion of lymphocytes in ALPS.

Figure 2. Aging ripk1−/− ripk3−/− casp8−/− animals develop an ALPS-like phenotype, yet they have a normal immune system when young.

(A) Lymphoid organs at 16 weeks.

(B) FACS analysis of cells stained with anti-CD3 and anti-B220 taken from 16-week old animals of the indicated genotypes.

(C, D) Percentage of CD3+B220+ cells among peripheral blood mononuclear cells in mice of the indicated genotypes and ages.

(E) Percentage of CD62LhiCD44− cells in CD4+ and CD8+ T cell populations from spleens of 4-week old mice of the indicated genotypes.

(F) CFSE dilution of 3-week old anti-CD3 and anti-CD28-activated splenic naïve CD4+ and CD8+ T cells. Blue line corresponds to ripk1+/+ripk3−/− casp8−/− cells and red line corresponds to ripk1−/− ripk3−/− casp8−/− cells.

TNFR1-induced caspase-8 activation contributes to perinatal lethality in ripk1−/− ripk3−/− mice

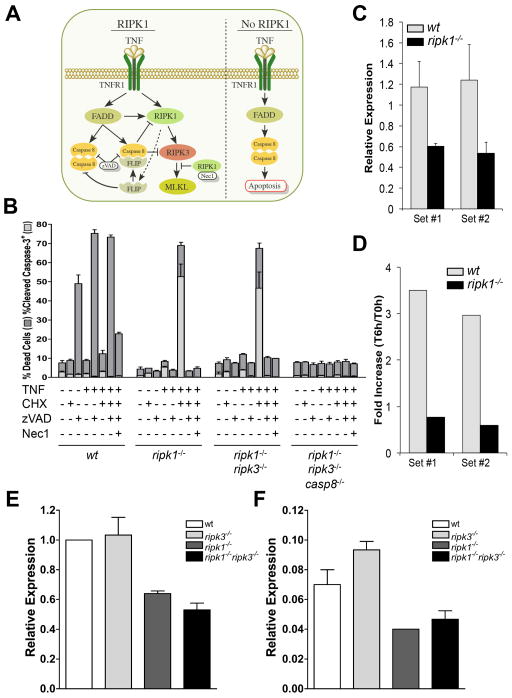

The role of caspase-8 in the postnatal lethality of ripk1−/− ripk3−/− animals suggests that RIPK1 functions to inhibit caspase-8-mediated apoptosis in some settings (Fig. 3A). Indeed, RIPK1-deficient primary MEF were strikingly sensitized to apoptosis induced by treatment with TNF plus low-dose cycloheximide (CHX), showing cleavage of caspase-3, and this cell death was blocked by the caspase inhibitor N-benzyloxycarbonyl-Val-Ala-Asp (O-Me) fluoromethyl ketone (zVAD) (Fig. 3B, S2A,B). This is consistent with earlier observations that ripk1−/− transformed MEF are sensitized for cell death induced by TNF plus CHX (Kelliher et al., 1998). Similarly, ripk1−/− ripk3−/− MEF but not ripk1−/− ripk3−/− casp8−/− MEF were sensitized to TNF plus CHX-induced apoptosis (Fig. 3B, S2A,B). Thus, the loss of RIPK1 sensitized cells to TNF-induced, caspase-8-dependent apoptosis. This is likely due to defects in expression of FLIP, since primary ripk1−/− MEF showed reduced basal levels of FLIP mRNA as compared to WT MEF (Fig. 3C) and did not up-regulate FLIP mRNA levels upon exposure to TNF (Fig. 3D). In contrast, we observed no alterations in expression of three other regulators of TNFR1 signaling, c-IAP1, c-IAP2, and X-IAP (Fig. S2C). Similarly, we observed that endogenous, constitutive expression of FLIP in spleen and lung was reduced in animals lacking RIPK1 (Fig. 3E,F). FLIP levels are well known to regulate sensitivity to TNF-induced apoptosis (Budd et al., 2006; Micheau et al., 2001; Wittkopf et al., 2013). FLIP is also required (in the form of the FADD-FLIP-caspase-8 complex) for inhibition of necroptosis induced by TNF (Oberst, et al., 2011), and thus, animals with low FLIP expression due to loss of RIPK1 may be sensitized to necroptosis. However, RIPK1 is required for TNF-induced necroptosis (Vandenabeele et al., 2010), as we observed in response to TNF plus zVAD, which triggered caspase-3-independent cell death in WT but not primary ripk1−/− MEF (Fig. 3B).

Figure 3. Loss of RIPK1 potentiates TNF-mediated apoptosis, which is independent of RIPK3.

(A) Schematic of the role of RIPK1 in cell death in response to TNF.

(B) Cell death assessed by propidium iodide and annexin V (dark grey bars) or cleaved caspase-3 staining (light grey bars) of primary MEF of the specified genotypes treated in the presence or absence of TNF (10 ng/mL), zVAD (50 μM), CHX (25 ng/mL), and/or Nec1 (30 μM) as indicated. Data is representative of three independent experiments. Error bars, s.d.

(C) Basal or (D) induced (10 ng/mL TNF for 6h) expression of cFLIPL determined via qPCR using two separate sets of primers (set #1 and set #2, see Methods for sequences).

(E,F) Expression of cFLIPL determined via qPCR using primer set #1 from the (E) spleen or (F) lung of P1 pups of the indicated genotypes. For qPCR data, relative expression (arbitrary units) is expressed as a ratio of cFLIPL versus control signal (L32), while fold increase represents ratio of relative expression from end of treatment with TNF (T6h) versus start of experiment (T0h).

See also Figure S2.

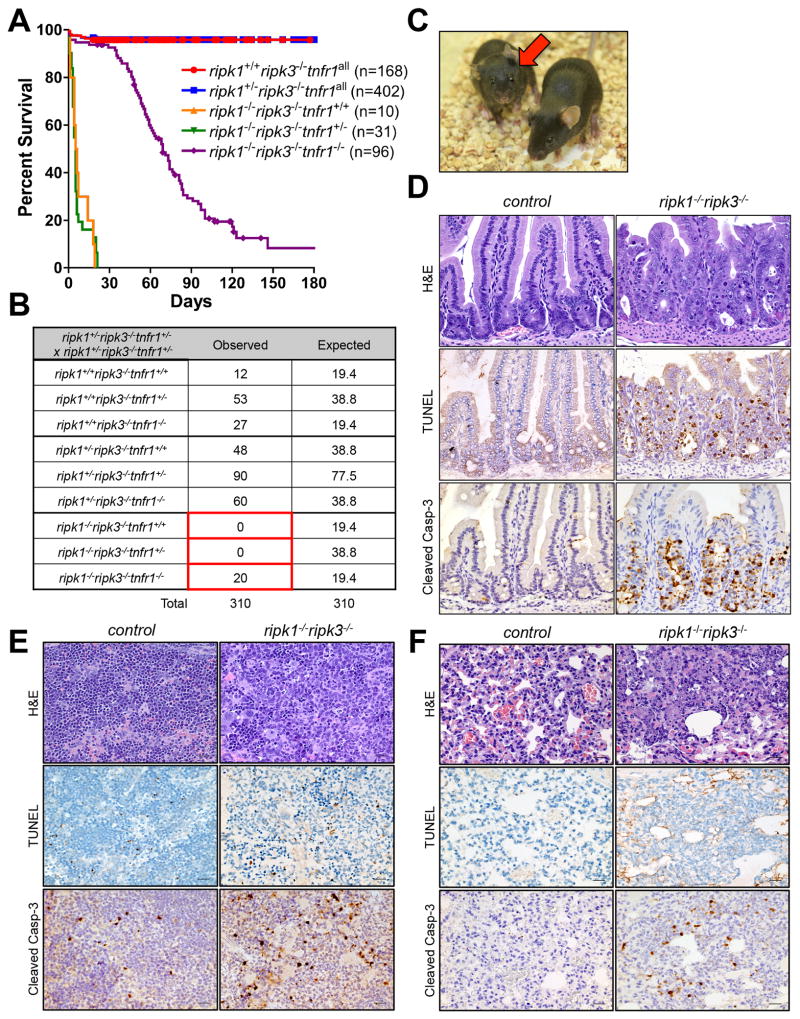

We therefore investigated the role of TNF in the postnatal lethality of ripk1−/− ripk3−/− mice. While ablation of tnfr1 in ripk1−/− mice delays but does not rescue postnatal lethality (Cusson et al., 2002)(Fig. S3A), we observed that ripk1−/− ripk3−/− tnfr1−/− mice survived weaning into adulthood at Mendelian frequencies (Fig. 4A–C). While these mice initially matured normally, and did not manifest ALPS (Fig. S3B), we noted mortality with time (Fig. 4A), and this was associated with blood bacteremia (Fig. S3C), decreased blood lymphocyte and increased blood neutrophil levels (Fig. S3D), consistent with sepsis. Even shortly after weaning (P25) intestinal morphology was disrupted with associated apoptosis (Fig. S3E), suggesting that a breakdown in barrier function eventually contributes to mortality in animals lacking tnfr1, ripk1, and ripk3. Nevertheless, ablation of tnfr1 clearly rescues perinatal lethality in ripk1−/− ripk3−/− mice.

Figure 4. Ablation of tnfr1 rescues the perinatal lethality of ripk1−/− ripk3−/− mice.

(A) Survival of pups from intercrosses of ripk1+/− ripk3−/− tnfr1+/− animals. ripk1−/− ripk3−/− tnfr1−/− survival was compared to ripk1−/− ripk3−/− tnfr1+/+ (p<0.0001) and ripk1−/− ripk3−/− tnfr1+/− (p<0.0001). ripk1−/− ripk3−/− tnfr1−/− survival was also compared to ripk1+/+ripk3−/− tnfr1all (p<0.0001) and ripk1+/− ripk3−/− tnfr1all (p<0.0001).

(B) Expected and observed frequency of genotypes in offspring at weaning from intercrosses of ripk1+/− ripk3−/− tnfr1+/− mice (p<0.0001 vs. expected Mendelian ratios).

(C) Photograph of 6-week old ripk1−/− ripk3−/− tnfr1−/− (arrow) and littermate control.

(D–F) Hematoxylin and eosin-stained, cleaved caspase-3 immunostaining, and TUNEL staining of sections of (D) duodenum, (E) spleen and (F) lung from ripk1−/− ripk3−/− or control animals. Images are representative of 3 independent experiments. See also Figure S3.

Our results show that ablation of casp8, fadd, or tnfr1 can prevent perinatal lethality in ripk1−/− ripk3−/− mice. Based on our in vitro studies, it is likely that one RIPK1 function is to sustain postnatal development by inhibiting TNFR1-induced, FADD-caspase-8-dependent apoptosis in one or more critical tissues. Indeed, we observed cell death accompanied by cleaved caspase-3 staining in the intestines, spleens, and lungs of ripk1−/− ripk3−/− animals (Fig. 4D–F). Consistent with our in vitro studies, we observed that the expression of FLIP was decreased in ripk1−/− ripk3−/− spleen and lung as compared to WT (Fig. 3E,F)(expression in intestine was too low to detect, not shown). Previous studies (Kellihar, et al., 1998) suggested that ripk1−/− mice show defects in not only these tissues but also in thymus and brown fat. Although we did not observe extensive thymocyte cell death in either ripk1−/− or ripk1−/− ripk3−/− mice (not shown), both brown fat and white fat in ripk1−/− ripk3−/− mice showed a marked depletion of lipid stores, without overt apoptosis (Fig. S3F, G), suggesting that these animals were energetically compromised.

TNFR1-induced RIPK1 activity causes E10.5 lethality in caspase-8-deficient mice

We observed that ablation of RIPK1 rescues the embryonic lethality of casp8−/− mice (Fig. 1A, S1D), consistent with the similar rescue of embryonic lethality in fadd−/− mice on the ripk1−/− background (Zhang, et al, 2011). Thus, although deletion of caspase-8 or fadd alone did not rescue the perinatal lethality seen in ripk1−/− mice, the embryonic lethality in fadd- or caspase-8-deficient animals is dependent on RIPK1. Because TNF-induced necroptosis in the absence of FADD-caspase-8-FLIP activity is dependent on RIPK1 ((Vandenabeele et al., 2010) and Fig. 3B), we asked if TNFR1 signaling might contribute to the E10.5 embryonic lethality in caspase-8- or fadd- deficient mice. Although casp8−/− tnfr1−/− mice did not survive to birth, we observed that these animals progressed well beyond E10.5 in development (Fig. 5A–C), as the fadd−/− tnfr1−/− embryos also did (Fig 5H). The E10.5 lethality in casp8−/− mice is associated with a failure to vascularize the yolk sac (Sakamaki et al., 2002), however casp8−/− tnfr1−/− mice showed normal vascular development (Fig. 5D). Similarly, animals lacking FLIP (cflar−/−) (Yeh et al., 2000) or FLIP and RIPK3 (Dillon, et al., 2012) die at E10.5, again with a failure to vascularize the yolk sac (Dillon, et al., 2012). As seen in casp8−/− tnfr1−/− mice, cflar−/− tnfr1−/− and cflar−/− tnfr1−/− ripk3−/− mice survived this embryonic stage as well (Fig. 5E–G, I). These data show that the E10.5 lethality of mice lacking FADD, FLIP, or caspase-8 is triggered by TNFR1 and, in the cases of FADD- or caspase-8-null embryos, dependent on RIPK1.

Figure 5. TNFR1-induced RIPK1 activity causes E10.5 lethality in caspase-8-deficient mice.

(A) Expected and observed frequency of genotypes in embryos between E14 and E17 from intercrosses of casp8+/− tnfr1−/− mice (p= 0.5658 vs. expected Mendelian ratios).

(B) Photograph of E16.5 casp8−/− tnfr1−/− embryo and casp8+/+ tnfr1−/− littermate control.

(C) Hematoxylin and eosin-stained sections of whole fixed E16.5 casp8−/− tnfr1−/− and casp8+/+ tnfr1−/− embryos.

(D) Photograph of vascularization of yolk sac from E16.5 casp8−/− tnfr1−/− embryo.

(E) Expected and observed frequency of genotypes in embryos between E14 and E17 from intercrosses of cflar+/− tnfr1−/− ripk3−/− mice (p= 0.2068 vs. expected Mendelian ratios).

(F) Photograph of E16.5 cflar−/− tnfr1−/− ripk3−/− embryo and cflar+/+tnfr1−/− ripk3−/− littermate control.

(G) Hematoxylin and eosin-stained sections of whole fixed E16.5 cflar−/− tnfr1−/− ripk3−/− and cflar+/+tnfr1−/− ripk3−/− embryos.

(E) Expected and observed frequency of genotypes in embryos between E14 and E17 from intercrosses of fadd+/− tnfr1−/− mice (p= 0.9858 vs. expected Mendelian ratios).

(I) Expected and observed frequency of genotypes in embryos between E14 and E17 from intercrosses of cflar+/− tnfr1−/− mice (p= 0.1897 vs. expected Mendelian ratios).

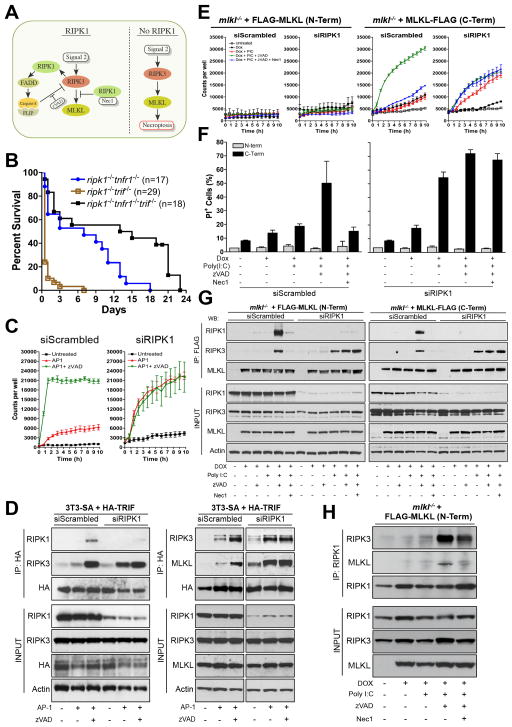

TRIF and interferons engage RIPK3-dependent lethality in ripk1−/− tnfr1−/− mice

While ablation of FADD, caspase-8, or TNFR1 rescues perinatal lethality in ripk1−/− ripk3−/− mice, it does not do so in ripk1−/− mice (Cusson et al., 2002; Zhang et al., 2011)(Fig. 1,4A, S1D, S3A). This suggests that a second signal, besides TNFR1, must engage RIPK3 to promote lethality in the absence of RIPK1 (Fig. 6A). In addition, in vitro evidence suggests that the signal that engages RIPK3 cannot be via TNFR1. Primary WT MEF underwent caspase-independent necrosis in response to TNF plus zVAD, which was inhibited by the RIPK1 inhibitor, Nec1 (Fig. 3B), as expected (Oberst et al., 2011; Vandenabeele et al., 2010) and absent in treated ripk1−/− MEF (Fig. 3B). Therefore, TNF-mediated necroptosis requires RIPK1, as previously described (Vandenabeele et al., 2010), as seen with other death ligands (Holler et al., 2000). However, our genetic results strongly indicated that lethal RIPK3 signaling can not only proceed independently of RIPK1, but that RIPK1 functions to inhibit this signaling in a critical postnatal setting (Fig. 6A). We therefore sought a second signal for RIPK3 activation that is exacerbated by ablation of RIPK1.

Figure 6. In the absence of RIPK1, RIPK3-MLKL-dependent cell death is potentiated in response to poly I:C.

(A) Model for the activation of RIPK3 via a RIPK1-independent mechanism.

(B) Survival of pups from intercrosses of ripk1+/− trif−/−, ripk1+/− tnfr1−/− or ripk1+/− tnfr1−/− trif−/− animals. Ripk1−/− tnfr1−/− trif−/− survival was compared to ripk1−/− tnfr1−/− (p=0.008) and ripk1−/− trif−/− (p<0.0001). ripk1−/− tnfr1−/− survival was compared to ripk1−/− trif−/− (p<0.0001).

(C) 3T3-SA cells stably expressing 2vFV-TRIF-HA were transfected with either scrambled or RIPK1 siRNA and treated with AP-1 dimerizer (10nM) in the absence or presence of zVAD (25 μM). Cell death was assessed by Sytox Green uptake using an Incucyte Kinetic Live Cell Imager. Data is representative of three independent experiments. Error bars, s.d.

(D) 3T3-SA expressing 2Fv- TRIF-HA were subjected to immunoprecipitation (IP) of HA following the transfection of either scrambled or RIPK1 siRNAs and 45 min treatment with AP-1 (10 nM) in absence or presence of zVAD (50 μM).

(E) Mlkl−/− MEF expressing DOX-inducible tagged MLKL (N-term FLAG-MLKL, left panel and C-Term MLKL-FLAG, right panel) were transfected with either scrambled or RIPK1 siRNAs and then treated with DOX (1 μg/ml), poly I:C (50 μg/mL), zVAD (50 μM) and/or Nec1 (30 μM) as indicated. Cell death assessed by Sytox Green uptake using an Incucyte Kinetic Live Cell Imager. Data is representative of two independent experiments. Error bars, s.d.

(F) Cell death of cells treated in (E) by propidium iodide uptake using flow cytometry 10h after treatment. Data is representative of two independent experiments. Error bars, s.d.

(G) In the same experiment as (E,F), MLKL was immunoprecipitated with anti-FLAG and co-immunoprecipiated proteins assessed by western blot. IP of MLKL via FLAG (N-Term, left panel, C-Term, right panel) of mlkl−/− MEF treated as indicated for 4h.

(H) IP of endogenous RIPK1 in mlkl−/− MEF expressing FLAG-MLKL (N-Term) treated as in (E). For all cases, immune complexes were detected by Western blotting with the indicated antibodies. See also Figure S4.

The DNA-dependent activator of interferon regulatory factors, DAI, can directly engage RIPK3 to promote necroptosis independently of RIPK1, but the presence or absence of RIPK1 does not affect this interaction (Upton et al., 2012). In contrast, poly I:C, signaling via TLR3 and TRIF, may promote necroptosis that is exacerbated by silencing RIPK1 (Kaiser et al., 2013). We therefore generated ripk1−/− tnfr1−/− trif−/− mice. Although few animals survived until weaning, we observed a significant delay in mortality as compared to ripk1−/− tnfr1−/− mice (p= 0.008) or ripk1−/− trif−/− (p<0.0001)(Fig. 6B). Therefore, signaling via TRIF may serve as one relevant “signal 2” to trigger RIPK3-dependent lethality in the absence of RIPK1 (Fig. 6A).

We then asked whether TRIF could engage RIPK3 in the absence of RIPK1. We stably expressed Fv2-TRIF-HA (a modification of an FKBP domain allowing dimerization upon addition of the rapalog, AP-20187 (AP-1) (Amara et al., 1997)) in 3T3-SA cells. Addition of dimerizer induced robust cell death only upon addition of zVAD or upon silencing of RIPK1 (without a requirement for zVAD) (Fig. 6C). Pull-down of TRIF optimally co-immunoprecipitated RIPK1, RIPK3, and MLKL in control cells only in the presence of AP-1 and zVAD (Fig. 6D). In contrast, in cells with silenced RIPK1, AP1 treatment was sufficient to pull down RIPK3 and MLKL, without a requirement for zVAD (Fig. 6D). Thus, TRIF can bind RIPK3 independently of RIPK1, and in the presence of RIPK1, caspase-8 activity (Kaiser et al., 2013) antagonizes RIPK3 function in necroptosis.

Consistent with these observations, we saw that poly I:C treatment of WT immortalized MEF induced cell death only upon addition of zVAD or upon silencing of RIPK1, without a requirement for zVAD (Fig. S4A, B). Silencing of caspase-8 similarly sensitized primary MEF to poly I:C, as described (Kaiser et al., 2013)(Fig. S4C). Nec1 inhibited cell death induced by poly I:C plus zVAD, but only in the presence of RIPK1 (Fig. S4A,B). We then employed immortalized mlkl−/− MEF, stably expressing an inducible FLAG-tagged MLKL to further interrogate these effects (Fig. 6E–H). Addition of zVAD plus poly I:C induced cell death in cells expressing C-terminal but not N-terminal tagged MLKL, and this death was inhibited by Nec1 (Fig. 6E,F). Both tagged forms of MLKL co-precipitated RIPK1 and RIPK3 under these necroptotic conditions, and this association was blocked by Nec1 in both cases (Fig. 6G). Upon silencing RIPK1, the cell death response to poly I:C, even in the absence of zVAD, was enhanced, and Nec1 did not prevent this cell death (Fig. 6E,F). RIPK3 co-precipitated with MLKL in RIPK1-silenced cells only in response to poly I:C, with no effect of Nec1 (Fig. 6G). In contrast, in immortalized WT MEF expressing N-terminal tagged MLKL, (as well as endogenous MLKL) treatment with TNF plus zVAD induced the association of MLKL, RIPK3, and RIPK1, which was lost upon treatment with Nec-1 or silencing of RIPK1 (Fig. S4D). Nec1 addition only partially reduced the amount of RIPK3 co-immunoprecipitated with RIPK1, but prevented its association with MLKL (Fig. 6H). The resulting cell death was MLKL dependent, as poly I:C-induced cell death in RIPK1-silenced cells was not observed in mlkl−/− cells (Fig. S4E,F). Therefore, in contrast to TNF-induced necroptosis, RIPK1 is dispensable for poly I:C-induced necroptosis, and can inhibit it, either through recruitment of caspase activity (blocked by zVAD), or in its Nec1-inhibited form, independently of caspase activity (Fig. 6A).

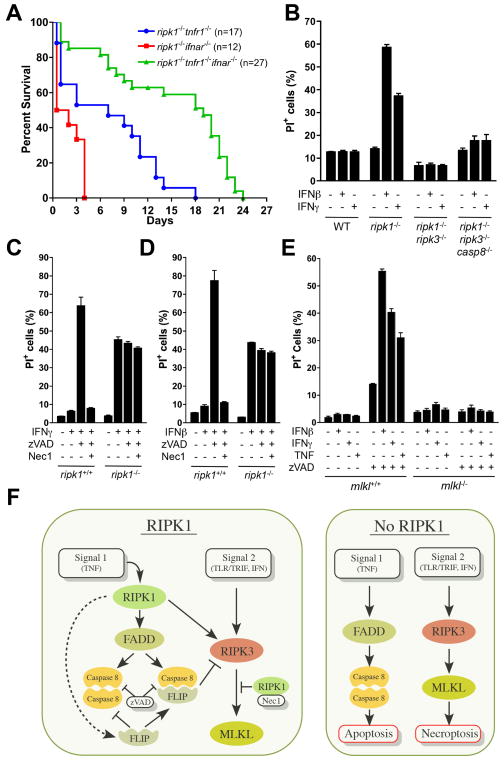

While deletion of TRIF significantly delayed lethality in ripk1−/− tnfr1−/− mice, most of these animals did not survive to weaning (Fig. 6B). TRIF is therefore not the only relevant “signal 2” that can engage RIPK3-MLKL interaction, antagonized by RIPK1 (Fig. 6A). Interferons (IFN) reportedly induce necroptosis (Thapa et al., 2013), and thus might represent such a signal. We therefore generated ripk1−/− tnfr1−/− ifnar−/− mice, lacking the type I IFN receptor. These animals survived significantly longer than did ripk1−/ tnfr1−/− mice (p<0.0001) or ripk1−/− ifnar−/− mice (p<0.0001) (Fig. 7A). As ifnar−/− mice possess receptors for type II IFN, we compared the effects of IFNβ and IFNγ on primary MEF in vitro. We observed that primary MEF lacking RIPK1 were sensitized to both type I and type II IFN-induced cell death that required RIPK3, independently of caspase-8 (Fig. 7B–D, S5A,B). In primary WT MEF, IFNs induced cell death only in the presence of zVAD, and this was inhibited by Nec1 (Fig. 7C,D). In contrast, IFN-induced cell death in RIPK1-deficient cells was unaffected by either zVAD or Nec1 (Fig. 7C,D), although the IFN response, as detected by expression of STAT1 or PKR was equivalent in WT and ripk1−/− cells (Fig. S5C,D). Cell death induced by IFN was not observed in primary MEF lacking MLKL (Fig. 7E, S5E,F), and was blocked by silencing or pharmacologic inhibition of PKR, as described (Thapa, et al., 2013), (Fig. S5G–J).

Figure 7. In the absence of RIPK1, RIPK3-dependent cell death is potentiated in response to interferons.

(A) Survival of pups from intercrosses of ripk1+/− ifnar−/−, ripk1+/− tnfr1−/− or ripk1+/− tnfr1−/− ifnar−/− animals. ripk1−/− tnfr1−/− ifnar−/− survival was compared to ripk1−/− tnfr1−/− (p=0.0001) and ripk1−/− ifnar−/− (p<0.0001). ripk1−/− tnfr1−/− survival was compared to ripk1−/− ifnar−/− (p=0.0079).

(B) Cell death assessed by propidium iodide uptake via flow cytometry of primary MEF of the specified genotypes treated in the presence or absence of Interferon-γ (IFNγ)(100 ng/mL) or Interferon-β (IFNβ) (1000 U/mL). Data is representative of three independent experiments. Error bars, s.d.

(C,D) Cell death assessed by propidium iodide uptake via flow cytometry of primary ripk1+/+ or ripk1−/− MEF treated in the presence or absence of (C) IFNγ (100 ng/mL), zVAD (25 μM), and/or Nec1 (30 μM) or (D) IFNβ (1000 U/mL), zVAD (25 μM), and/or Nec1 (30 μM) as indicated. Data is representative of three independent experiments. Error bars, s.d.

(E) Cell death assessed by propidium iodide uptake via flow cytometry of primary mlkl+/+ or mlkl−/− MEF treated in the presence or absence of IFNγ (100 ng/mL), IFNβ (1000 U/mL), TNF (10ng/mL), and/or zVAD (25 μM) as indicated. Data is representative of two independent experiments. Error bars, s.d.

(F) Model of RIPK1 function in cell death.

See also Figure S5–7.

Interferon treatment of primary WT or ripk1−/− MEF promoted similar up-regulation of MLKL but not RIPK3 (Fig. S6A–C), as described (Thapa et al., 2013), and this up-regulation was not observed upon treatment with TNF or poly I:C (Fig. S6D–F). We noted that MLKL levels were consistently lower in ripk1−/− vs WT in three matched sets of primary MEF (Fig. S6A and data not shown). It is possible that this reflects selection against expression of MLKL in ripk1−/− MEF, further supporting the idea that RIPK1 functions to prevent MLKL-dependent death. The increased expression of MLKL induced by IFNs may contribute to necroptosis, but this alone cannot account for the death observed in ripk1−/− MEF, since the levels in these cells did not exceed those seen in WT MEF (Fig. S6A), and the effects were dependent on RIPK3 (Fig. 7B, S5A,B).

While engagement of RIPK3 (and MLKL) promotes necroptosis, which may contribute to the perinatal death of ripk1−/− mice, the RIPK3-MLKL interaction also promotes inflammatory cytokine production (Kang et al., 2013). We therefore compared the in vivo cytokine levels in mice injected with lipopolysaccharide (LPS) (Fig. S7). In comparison to WT, ripk3−/− mice, or ripk3−/− casp8−/− mice, animals lacking ripk1, ripk3, and casp8 showed reduced cytokine levels. Therefore, it is likely that RIPK1 promotes cytokine production in response to LPS, as observed by others (Lukens et al., 2013), although this did not appear to depend on the presence of RIPK3 or caspase-8 (except in the case of IL-1β, as described (Gurung et al., 2014)). Therefore, it is unlikely that a lack of RIPK1, per se, directly promotes RIPK-MLKL-dependent inflammation, at least via TLR engagement. It is possible, however, that a failure to up-regulate key cytokines in response to establishment of the microbiota around birth may contribute to postnatal lethality in ripk1−/− mice. Although no evidence of bacterial sepsis has been found in these animals (Cusson et al., 2002; Kelliher et al., 1998), we cannot formally rule out this possibility.

DISCUSSION

The elucidation of the function of a gene from mutant phenotypes and the effects of other mutations on those phenotypes is often confounded by the complexities of the genetic interactions. Our finding that the perinatal lethality of ripk1−/− mice can be prevented with combinations of additional mutations permits two broad conclusions that are, on the surface, fairly straightforward: a) RIPK1 functions to prevent perinatal lethality caused by the activity of TNFR1, FADD, and caspase-8 and b) RIPK1 functions to prevent perinatal lethality caused by the activity of TRIF, IFN, and RIPK3. Thus, these proteins operate in two different cell death pathways (the death receptor pathway of apoptosis, and RIPK1-independent necroptosis), and while the genetic evidence alone does not permit us to formally conclude that RIPK1 is required only to prevent both pathways of cell death engaged following birth, the results are highly suggestive of this conclusion.

The prevention of perinatal lethality in the ripk1−/− mouse by ablation of these two cell death pathways was not fully anticipated based on previous studies in vitro or in vivo. Although transformed MEF from ripk1−/− mice display increased sensitivity to TNF-induced apoptosis (Kelliher et al., 1998), RIPK1 has also been shown to promote FADD-dependent caspase-8 activation in response to TNF (Feoktistova et al., 2011; Oberst et al., 2011; Tenev et al., 2011; Zhang et al., 2011) and other stimuli (Kreuz et al., 2004; Lin et al., 2000; Ma et al., 2005). Similarly, RIPK3-dependent necroptosis induced by TNF (Degterev et al., 2005), TLR-ligands (He et al., 2011), or interferons (Thapa et al., 2013) is effectively blocked by the RIPK1 inhibitor, Nec1, suggesting that RIPK1 functions via its kinase activity to promote RIPK3 activation and necroptosis, an idea supported by structural studies of RIPK1-RIPK3 interactions (Li et al., 2012). Our results extend the latter conclusion and suggest that under conditions in which RIPK3 is activated independently of RIPK1 (TRIF, IFNs) RIPK1 inhibits necroptosis by recruiting zVAD-inhibitable caspase activity, likely by the action of FADD-caspase-8-FLIP (Green, et al., 2011). In the absence of caspase activity, Nec1 inhibits necroptosis in a RIPK1-dependent manner, suggesting that the Nec1-bound RIPK1 disrupts RIPK3 function. Indeed, we found that Nec1 inhibits the association of RIPK3 and MLKL induced by the TLR3 ligand, poly I:C, but only in the presence of RIPK1 (Fig. 6G,H).

Our in vitro and in vivo evidence show that loss of RIPK1 sensitizes primary cells to both TNFR1-FADD-caspase-8-mediated apoptosis induced by TNF and RIPK3-mediated necroptosis induced by TLR ligation (via TRIF) or interferons. We have previously shown that enforced oligomerization of RIPK3 is sufficient to induce MLKL-dependent necroptosis (Tait et al., 2013). Therefore, oligomerization of TRIF, and thus RIPK3, can promote the activation of the latter independently of RIPK1. When RIPK1 is present, recruited caspase activity prevents this activation and interaction with MLKL. These results are consistent with models of RIPK1 and RIPK3 interaction (Li et al., 2012). In the case of interferon exposure, we propose that PKR contributes to RIPK1-independent activation of RIPK3, as suggested by others (Thapa, et al, 2013), although the precise mechanisms remain obscure.

In mice lacking both RIPK1 and RIPK3, perinatal lethality is fully penetrant, although our data shows that this is dependent on TNFR1, FADD, and caspase-8. Our models suggest that apoptosis, engaged by the latter, is responsible for this lethality. Indeed, we observed widespread apoptosis in these animals. While apoptosis is readily detected by histological methods, it is more difficult to detect necroptosis, and therefore we can only speculate at this point that perinatal lethality in ripk1−/− mice is due to a mixture of apoptotic and necrotic death in the same tissues undergoing apoptosis in the ripk1−/− ripk3−/− mice. Further, since RIPK3-MLKL interactions can produce inflammatory effects, apparently independently of cell death (Kang et al., 2013), we cannot exclude that such inflammation, rather than cell death, contributes to perinatal lethality in the ripk1−/− mice, although widespread inflammation has not been observed in these animals (Kelliher et al., 1998). Such an effect, however, would be excluded in the case of ripk1−/− ripk3−/− mice. In the latter, we observed some delay in perinatal lethality versus ripk1−/− mice, supporting this idea.

Our data support a model of RIPK1 function in development and post-natal life (Fig. 7F). Since ablation of RIPK1 sensitizes for both TNFR1-FADD-caspase-8-dependent and RIPK3-dependent lethality, we must assume that these pathways are not engaged prior to birth. FADD- or caspase-8-deficient mice die in utero and this embryonic lethality is fully prevented upon ablation of RIPK3 (Dillon et al., 2012; Kaiser et al., 2011; Oberst et al., 2011). However, since RIPK1-deficient animals survive to birth, the signals responsible for such embryonic lethality are not held in check by RIPK1, and indeed are promoted by it. Prior to birth, RIPK1 promotes TNFR-mediated lethality at E10.5 in animals lacking FADD, caspase-8, or FLIP (Zhang et al., 2011 and Figure 5), and lethality at a later developmental check point that might be mediated by similar signals, perhaps from other TNFR-related receptors (or another signal with the properties of signal 1). We observed that cells lacking RIPK1 do not undergo necroptosis in response to TNFR ligation, consistent with other observations (Vandenabeele et al., 2010), supporting the idea that the later-stage lethality seen in casp8−/− tnfr1−/− embryos is mediated by a TNFR1-like necroptosis-inducing signal. At the time of birth, RIPK1 is required to prevent a TNFR1-induced FADD and caspase-8-dependent lethality in ripk1−/− ripk3−/− animals, possibly relating to a failure to up-regulate FLIP in response to TNFR1 signaling. If so, FLIP, which is required for development beyond E10.5 must be expressed at that time independently of RIPK1.

Post birth, RIPK1 is also required to prevent RIPK3-dependent lethality promoted by TRIF, IFN, and possibly other signals. It is likely that this inhibition is mediated by the recruitment, via RIPK1, of FADD-caspase-8-FLIP, which does not promote apoptosis but which functions catalytically to inhibit RIPK3 function (Green, et al., 2011), directly engaged by these signals.

Mice with a kinase-dead mutation of RIPK1 show normal development and maturation, although cells from these animals appear to be defective in TNF-induced necroptosis (Newton et al., 2014). The mechanisms by which the kinase activity of RIPK1 either promotes or prevents cell death in other contexts still remain obscure. Strikingly, mice with a kinase-dead mutation of RIPK3 die at E10.5, and were rescued to birth by ablation of RIPK1, or fully rescued by ablation of caspase-8 (Newton et al., 2014), indicating that RIPK3 can itself engage both RIPK1 and caspase-8. While it remains unclear why kinase-dead RIPK3 is hyper-active in this regard, the results are consistent with the pathways described; disruption of either the necroptotic pathway (by mutation of the RIPK3 kinase domain) or the apoptotic pathway (by ablation of caspase-8, FADD, or FLIP) “unbalances” the system in favor of lethality by the other pathway. Ablation of RIPK1 similarly unbalances these pathways, but only after birth, suggesting that the inhibitory function of RIPK1 only becomes essential when additional signals (such as TLR/TRIF and IFN) manifest.

RIPK1 is under complex regulation by a number of ubiquitin ligases and deubiquitinases. CIAP1/2 mediate K63 ubiquitinylation of RIPK1, while LUBAC (HOIP, HOIL, sharpin) causes linear ubiquitylation of RIPK1, both of which are involved in recruitment of NEMO (Bertrand et al., 2008; Gerlach et al., 2011) The deubiquitinase CYLD removes the K63-Ub, promoting activity in necroptosis (Moquin et al., 2013) In contrast, A20 “edits” these linkages from K63 to K48 (Wertz et al., 2004), destabilizing the protein. How these interactions may impact on the complex patterns we observed for the maintenance of perinatal life remain obscure. However, one might expect that intracellular pathogens that disrupt elements of this process at any of a variety of points would trigger cell death, preventing further spread of the pathogen. If so, this may suggest a reason why this complex interrelationship exists, and why ablation of specific elements (including RIPK1, FADD, caspase-8, FLIP, and the kinase activity of RIPK3) push the system to lethality. It may also be relevant that the tissues that are most affected by such disruption (intestine, lung, skin, endothelium, hematopoietic cells) (Khan et al., 2014) represent barriers that are potentially engaged by such pathogens.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Mice, In vivo Treatments, and Serum Analysis

Ripk3−/− casp8−/− (Oberst et al., 2011), ripk3−/− fadd−/− (Dillon et al., 2012), ripk1−/− (Kelliher et al., 1998), tnfr1−/− (Pfeffer et al., 1993), cflar−/− (Yeh et al., 2000), trif−/−(Yamamoto et al., 2003), and ifnar−/− (Muller et al., 1994) mice have been previously described. The St. Jude Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee approved all procedures in accordance with the Guide for the Care and Use of Animals.

Cell lines

Primary murine embryonic fibroblasts (MEF) were generated by mating animals of the required genotypes and harvesting embryos at E12–E14 based on palpation. Following removal of the head and fetal liver, a single suspension was generated from the remaining parts of the embryo and plated in DMEM supplemented with 10% FCS, L-glutamine, pen/strep, 55 μM β-mercaptoethanol, 1 mM sodium pyruvate and non-essential amino acids (GIBCO). All experiments on primary MEF were performed on cells no older than passage 3, and data shown represents experiments using independently derived MEF. Some of the primary MEFS were immortalized with SV40, and maintained in DMEM as above except with 5% FCS.

For further experimental procedures, please see the Extended Experimental Procedures.

Supplementary Material

HIGHLIGHTS.

Lethality in ripk1−/− mice is rescued by ablation of ripk3 with either casp8 or fadd.

TNF induces apoptosis and TRIF or IFN induce necroptosis in ripk1−/− cells.

Ripk1−/− ripk3−/− tnfr1−/− mice reach adulthood.

Lethality in ripk1−/− mice is delayed by deleting tnfr1 with either trif or ifnar.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Mao Yang, Patrick Fitzgerald and Margareth Barr for extensive technical assistance. The work was supported by grants from the U.S. National Institutes of Health and the American Lebanese Syrian Associated Charities.

Footnotes

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

C.P.D., R.W., D.A.R. and D.R.G conceived and designed the study,. C.P.D. and T.B. designed and conducted mouse breedings. R.W., C.P.D., J.C., K.V., D.A.R., G.Q., and J.C. performed experiments. L.J.J. performed the histology, and P.G. and T.K. provided cytokine data from challenged animals. Y.G and F.L provided essential reagents. M.A.K. produced the ripk1−/− animals and provided intellectual input.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Amara JF, Clackson T, Rivera VM, Guo T, Keenan T, Natesan S, Pollock R, Yang W, Courage NL, Holt DA, et al. A versatile synthetic dimerizer for the regulation of protein-protein interactions. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 1997;94:10618–10623. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.20.10618. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bertrand MJ, Milutinovic S, Dickson KM, Ho WC, Boudreault A, Durkin J, Gillard JW, Jaquith JB, Morris SJ, Barker PA. cIAP1 and cIAP2 facilitate cancer cell survival by functioning as E3 ligases that promote RIP1 ubiquitination. Molecular cell. 2008;30:689–700. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2008.05.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bidere N, Su HC, Lenardo MJ. Genetic disorders of programmed cell death in the immune system. Annu Rev Immunol. 2006;24:321–352. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.24.021605.090513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Biton S, Ashkenazi A. NEMO and RIP1 control cell fate in response to extensive DNA damage via TNF-alpha feedforward signaling. Cell. 2011;145:92–103. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2011.02.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Budd RC, Yeh WC, Tschopp J. cFLIP regulation of lymphocyte activation and development. Nat Rev Immunol. 2006;6:196–204. doi: 10.1038/nri1787. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cho YS, Challa S, Moquin D, Genga R, Ray TD, Guildford M, Chan FK. Phosphorylation-driven assembly of the RIP1-RIP3 complex regulates programmed necrosis and virus-induced inflammation. Cell. 2009;137:1112–1123. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.05.037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cusson N, Oikemus S, Kilpatrick ED, Cunningham L, Kelliher M. The death domain kinase RIP protects thymocytes from tumor necrosis factor receptor type 2-induced cell death. J Exp Med. 2002;196:15–26. doi: 10.1084/jem.20011470. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Degterev A, Hitomi J, Germscheid M, Ch’en IL, Korkina O, Teng X, Abbott D, Cuny GD, Yuan C, Wagner G, et al. Identification of RIP1 kinase as a specific cellular target of necrostatins. Nature chemical biology. 2008;4:313–321. doi: 10.1038/nchembio.83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Degterev A, Huang Z, Boyce M, Li Y, Jagtap P, Mizushima N, Cuny GD, Mitchison TJ, Moskowitz MA, Yuan J. Chemical inhibitor of nonapoptotic cell death with therapeutic potential for ischemic brain injury. Nature chemical biology. 2005;1:112–119. doi: 10.1038/nchembio711. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dillon CP, Oberst A, Weinlich R, Janke LJ, Kang TB, Ben-Moshe T, Mak TW, Wallach D, Green DR. Survival function of the FADD-CASPASE-8-cFLIP(L) complex. Cell Rep. 2012;1:401–407. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2012.03.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feoktistova M, Geserick P, Kellert B, Dimitrova DP, Langlais C, Hupe M, Cain K, MacFarlane M, Hacker G, Leverkus M. cIAPs block Ripoptosome formation, a RIP1/caspase-8 containing intracellular cell death complex differentially regulated by cFLIP isoforms. Molecular cell. 2011;43:449–463. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2011.06.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Festjens N, Vanden Berghe T, Cornelis S, Vandenabeele P. RIP1, a kinase on the crossroads of a cell’s decision to live or die. Cell death and differentiation. 2007;14:400–410. doi: 10.1038/sj.cdd.4402085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gerlach B, Cordier SM, Schmukle AC, Emmerich CH, Rieser E, Haas TL, Webb AI, Rickard JA, Anderton H, Wong WW, et al. Linear ubiquitination prevents inflammation and regulates immune signalling. Nature. 2011;471:591–596. doi: 10.1038/nature09816. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Green DR, Oberst A, Dillon CP, Weinlich R, Salvesen GS. RIPK-dependent necrosis and its regulation by caspases: a mystery in five acts. Molecular cell. 2011;44:9–16. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2011.09.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gurung P, Anand PK, Malireddi RK, Vande Walle L, Van Opdenbosch N, Dillon CP, Weinlich R, Green DR, Lamkanfi M, Kanneganti TD. FADD and caspase-8 mediate priming and activation of the canonical and noncanonical Nlrp3 inflammasomes. Journal of immunology. 2014;192:1835–1846. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1302839. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- He S, Liang Y, Shao F, Wang X. Toll-like receptors activate programmed necrosis in macrophages through a receptor-interacting kinase-3-mediated pathway. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2011;108:20054–20059. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1116302108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holler N, Zaru R, Micheau O, Thome M, Attinger A, Valitutti S, Bodmer JL, Schneider P, Seed B, Tschopp J. Fas triggers an alternative, caspase-8-independent cell death pathway using the kinase RIP as effector molecule. Nature immunology. 2000;1:489–495. doi: 10.1038/82732. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaiser WJ, Sridharan H, Huang C, Mandal P, Upton JW, Gough PJ, Sehon CA, Marquis RW, Bertin J, Mocarski ES. Toll-like receptor 3-mediated necrosis via TRIF, RIP3, and MLKL. The Journal of biological chemistry. 2013;288:31268–31279. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M113.462341. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaiser WJ, Upton JW, Long AB, Livingston-Rosanoff D, Daley-Bauer LP, Hakem R, Caspary T, Mocarski ES. RIP3 mediates the embryonic lethality of caspase-8-deficient mice. Nature. 2011;471:368–372. doi: 10.1038/nature09857. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kang TB, Yang SH, Toth B, Kovalenko A, Wallach D. Caspase-8 blocks kinase RIPK3-mediated activation of the NLRP3 inflammasome. Immunity. 2013;38:27–40. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2012.09.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelliher MA, Grimm S, Ishida Y, Kuo F, Stanger BZ, Leder P. The death domain kinase RIP mediates the TNF-induced NF-kappaB signal. Immunity. 1998;8:297–303. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(00)80535-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khan N, Lawlor KE, Murphy JM, Vince JE. More to life than death: molecular determinants of necroptotic and non-necroptotic RIP3 kinase signaling. Current opinion in immunology. 2014;26:76–89. doi: 10.1016/j.coi.2013.10.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kreuz S, Siegmund D, Rumpf JJ, Samel D, Leverkus M, Janssen O, Hacker G, Dittrich-Breiholz O, Kracht M, Scheurich P, et al. NFkappaB activation by Fas is mediated through FADD, caspase-8, and RIP and is inhibited by FLIP. The Journal of cell biology. 2004;166:369–380. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200401036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li J, McQuade T, Siemer AB, Napetschnig J, Moriwaki K, Hsiao YS, Damko E, Moquin D, Walz T, McDermott A, et al. The RIP1/RIP3 necrosome forms a functional amyloid signaling complex required for programmed necrosis. Cell. 2012;150:339–350. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2012.06.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin Y, Devin A, Cook A, Keane MM, Kelliher M, Lipkowitz S, Liu ZG. The death domain kinase RIP is essential for TRAIL (Apo2L)-induced activation of IkappaB kinase and c-Jun N-terminal kinase. Molecular and cellular biology. 2000;20:6638–6645. doi: 10.1128/mcb.20.18.6638-6645.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lukens JR, Vogel P, Johnson GR, Kelliher MA, Iwakura Y, Lamkanfi M, Kanneganti TD. RIP1-driven autoinflammation targets IL-1alpha independently of inflammasomes and RIP3. Nature. 2013;498:224–227. doi: 10.1038/nature12174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma Y, Temkin V, Liu H, Pope RM. NF-kappaB protects macrophages from lipopolysaccharide-induced cell death: the role of caspase 8 and receptor-interacting protein. The Journal of biological chemistry. 2005;280:41827–41834. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M510849200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meylan E, Burns K, Hofmann K, Blancheteau V, Martinon F, Kelliher M, Tschopp J. RIP1 is an essential mediator of Toll-like receptor 3-induced NF-kappa B activation. Nature immunology. 2004;5:503–507. doi: 10.1038/ni1061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Micheau O, Lens S, Gaide O, Alevizopoulos K, Tschopp J. NF-kappaB signals induce the expression of c-FLIP. Molecular and cellular biology. 2001;21:5299–5305. doi: 10.1128/MCB.21.16.5299-5305.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moquin DM, McQuade T, Chan FK. CYLD deubiquitinates RIP1 in the TNFalpha-induced necrosome to facilitate kinase activation and programmed necrosis. PloS one. 2013;8:e76841. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0076841. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moujalled DM, Cook WD, Okamoto T, Murphy J, Lawlor KE, Vince JE, Vaux DL. TNF can activate RIPK3 and cause programmed necrosis in the absence of RIPK1. Cell death & disease. 2013;4:e465. doi: 10.1038/cddis.2012.201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muller U, Steinhoff U, Reis LF, Hemmi S, Pavlovic J, Zinkernagel RM, Aguet M. Functional role of type I and type II interferons in antiviral defense. Science. 1994;264:1918–1921. doi: 10.1126/science.8009221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murphy JM, Czabotar PE, Hildebrand JM, Lucet IS, Zhang JG, Alvarez-Diaz S, Lewis R, Lalaoui N, Metcalf D, Webb AI, et al. The Pseudokinase MLKL Mediates Necroptosis via a Molecular Switch Mechanism. Immunity. 2013;39:443–453. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2013.06.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Newton K, Dugger DL, Wickliffe KE, Kapoor N, de Almagro MC, Vucic D, Komuves L, Ferrando RE, French DM, Webster J, et al. Activity of protein kinase RIPK3 determines whether cells die by necroptosis or apoptosis. Science. 2014;343:1357–1360. doi: 10.1126/science.1249361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oberst A, Dillon CP, Weinlich R, McCormick LL, Fitzgerald P, Pop C, Hakem R, Salvesen GS, Green DR. Catalytic activity of the caspase-8-FLIP(L) complex inhibits RIPK3-dependent necrosis. Nature. 2011;471:363–367. doi: 10.1038/nature09852. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pfeffer K, Matsuyama T, Kundig TM, Wakeham A, Kishihara K, Shahinian A, Wiegmann K, Ohashi PS, Kronke M, Mak TW. Mice deficient for the 55 kd tumor necrosis factor receptor are resistant to endotoxic shock, yet succumb to L. monocytogenes infection. Cell. 1993;73:457–467. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(93)90134-c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rajput A, Kovalenko A, Bogdanov K, Yang SH, Kang TB, Kim JC, Du J, Wallach D. RIG-I RNA helicase activation of IRF3 transcription factor is negatively regulated by caspase-8-mediated cleavage of the RIP1 protein. Immunity. 2011;34:340–351. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2010.12.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sakamaki K, Inoue T, Asano M, Sudo K, Kazama H, Sakagami J, Sakata S, Ozaki M, Nakamura S, Toyokuni S, et al. Ex vivo whole-embryo culture of caspase-8-deficient embryos normalize their aberrant phenotypes in the developing neural tube and heart. Cell death and differentiation. 2002;9:1196–1206. doi: 10.1038/sj.cdd.4401090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tait SW, Oberst A, Quarato G, Milasta S, Haller M, Wang R, Karvela M, Ichim G, Yatim N, Albert ML, et al. Widespread mitochondrial depletion via mitophagy does not compromise necroptosis. Cell Rep. 2013;5:878–885. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2013.10.034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tenev T, Bianchi K, Darding M, Broemer M, Langlais C, Wallberg F, Zachariou A, Lopez J, MacFarlane M, Cain K, et al. The Ripoptosome, a signaling platform that assembles in response to genotoxic stress and loss of IAPs. Molecular cell. 2011;43:432–448. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2011.06.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thapa RJ, Nogusa S, Chen P, Maki JL, Lerro A, Andrake M, Rall GF, Degterev A, Balachandran S. Interferon-induced RIP1/RIP3-mediated necrosis requires PKR and is licensed by FADD and caspases. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2013;110:E3109–3118. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1301218110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Upton JW, Kaiser WJ, Mocarski ES. DAI/ZBP1/DLM-1 complexes with RIP3 to mediate virus-induced programmed necrosis that is targeted by murine cytomegalovirus vIRA. Cell Host Microbe. 2012;11:290–297. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2012.01.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vallabhapurapu S, Matsuzawa A, Zhang W, Tseng PH, Keats JJ, Wang H, Vignali DA, Bergsagel PL, Karin M. Nonredundant and complementary functions of TRAF2 and TRAF3 in a ubiquitination cascade that activates NIK-dependent alternative NF-kappaB signaling. Nature immunology. 2008;9:1364–1370. doi: 10.1038/ni.1678. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vandenabeele P, Declercq W, Van Herreweghe F, Vanden Berghe T. The role of the kinases RIP1 and RIP3 in TNF-induced necrosis. Sci Signal. 2010;3:re4. doi: 10.1126/scisignal.3115re4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Varfolomeev E, Blankenship JW, Wayson SM, Fedorova AV, Kayagaki N, Garg P, Zobel K, Dynek JN, Elliott LO, Wallweber HJ, et al. IAP antagonists induce autoubiquitination of c-IAPs, NF-kappaB activation, and TNFalpha-dependent apoptosis. Cell. 2007;131:669–681. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.10.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vince JE, Wong WW, Khan N, Feltham R, Chau D, Ahmed AU, Benetatos CA, Chunduru SK, Condon SM, McKinlay M, et al. IAP antagonists target cIAP1 to induce TNFalpha-dependent apoptosis. Cell. 2007;131:682–693. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.10.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang L, Du F, Wang X. TNF-alpha induces two distinct caspase-8 activation pathways. Cell. 2008;133:693–703. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2008.03.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wertz IE, O’Rourke KM, Zhou H, Eby M, Aravind L, Seshagiri S, Wu P, Wiesmann C, Baker R, Boone DL, et al. De-ubiquitination and ubiquitin ligase domains of A20 downregulate NF-kappaB signalling. Nature. 2004;430:694–699. doi: 10.1038/nature02794. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wittkopf N, Gunther C, Martini E, He G, Amann K, He YW, Schuchmann M, Neurath MF, Becker C. Cellular FLICE-like inhibitory protein secures intestinal epithelial cell survival and immune homeostasis by regulating caspase-8. Gastroenterology. 2013;145:1369–1379. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2013.08.059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wong WW, Gentle IE, Nachbur U, Anderton H, Vaux DL, Silke J. RIPK1 is not essential for TNFR1-induced activation of NF-kappaB. Cell death and differentiation. 2010;17:482–487. doi: 10.1038/cdd.2009.178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamamoto M, Sato S, Hemmi H, Hoshino K, Kaisho T, Sanjo H, Takeuchi O, Sugiyama M, Okabe M, Takeda K, et al. Role of adaptor TRIF in the MyD88-independent toll-like receptor signaling pathway. Science. 2003;301:640–643. doi: 10.1126/science.1087262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yeh WC, Itie A, Elia AJ, Ng M, Shu HB, Wakeham A, Mirtsos C, Suzuki N, Bonnard M, Goeddel DV, et al. Requirement for Casper (c-FLIP) in regulation of death receptor-induced apoptosis and embryonic development. Immunity. 2000;12:633–642. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(00)80214-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang H, Zhou X, McQuade T, Li J, Chan FK, Zhang J. Functional complementation between FADD and RIP1 in embryos and lymphocytes. Nature. 2011;471:373–376. doi: 10.1038/nature09878. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang SQ, Kovalenko A, Cantarella G, Wallach D. Recruitment of the IKK signalosome to the p55 TNF receptor: RIP and A20 bind to NEMO (IKKgamma) upon receptor stimulation. Immunity. 2000;12:301–311. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(00)80183-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.