The siege of Bamyan (Dari: محاصره بامیان) took place in the spring of 1221 A.D. during the Mongol invasion of Khorasan by an army under the leadership of Genghis Khan, ruler of the Mongol Empire, who was in pursuit of Sultan Jalal al-Din Mangburni, the last ruler of the Khwarazmian Empire. Genghis Khan crossed the Hindu Kush and after that besieged the citadel of Shahr-e-Gholghola near Bamyan, northwest of Kabul, in present-day Afghanistan. The siege had led to a devastating attack that left the city in ruins.[3]

| Siege of Bamyan | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Mongol invasion of Khorasan | |||||||

Ruins of modern-day Shahr-e-Gholghola | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

| Mongol Empire | Khwarazmian Empire | ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

| Genghis Khan | Jalal al-Din Mangburni | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

| Heavy[1] | All killed[2] | ||||||

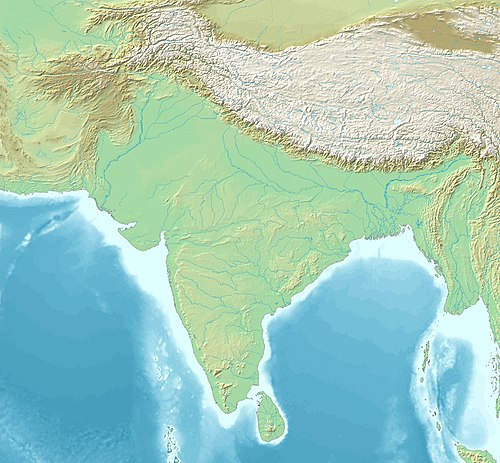

Location of the siege on a map of modern Afghanistan | |||||||

Background

editAfter besieging Taloqan for several months,[4] the Mongols of the Khagan Genghis Khan[5] marched to confront the Shah Jalal al-Din Mangburni, the last representative of the Khwarazmian Empire, who had formed a new Muslim army in what is now Afghanistan[6] and had defeated a Mongol army at the Battle of Parwan.[7]

Based on Al-Idrisi,[8] the demographer Tertius Chandler noted that Bamyan was three times smaller than Balkh in 1150. Chandler estimated that Balkh had a population of about thirty thousand people (a rounded estimate) and calculated that the Friday Mosque of Bamyan had a capacity of about nine thousand people.[9]

Siege

editWhen the Mongols arrived before Bamyan, the inhabitants made it clear that they intended to resist by force, leading both sides to deploy archers and catapults.[10] During the siege, however, Mutukan[note 1]—the eldest son of Chagatai Khan[11] and the Khagan’s favourite grandson[12]—was struck by an arrow and died soon afterward. This event led his grandfather, Genghis Khan, to order that all works aimed at capturing the fortress be accelerated.[13] According to certain accounts, Jalal al-Din Mangburni’s daughter revealed a secret entrance to the Mongols, enabling them to take the city.[14] No quarter was given during the subsequent fighting,[15] which is thought to have lasted for roughly a month.[16] The Khagan was deeply grieved by the death of his grandson,[17] and, upon taking the city, he issued a yasak (edict) commanding that every person, animal, bird, or wild creature in Bamyan be killed and that no booty be taken.[18] Not even pregnant women were spared.[19] He further ordered that no one inform his son Chagatai of what had occurred. When Chagatai eventually arrived and asked about Mutukan, the Khagan informed him of the loss[20] but commanded him not to weep. Chagatai therefore turned to eating and drinking to dull his grief and, under a pretext, withdrew to the steppe so that he might weep alone without disobeying his father.[21]

Aftermath

editAccording to Yaqub al-Herawi, all the inhabitants of the city were killed.[22][23] The city remained in ruins for many years and became known as Mao-Kurgan[24] or Ma'u-Baligh, which in Persian means “cursed city.”[25] It was also referred to as the “city of sorrows” or the “city of cries,” reflecting the deaths of its inhabitants during the Mongol conquest.[26][27] Today, the site of the ancient city of Bamyan is a UNESCO World Heritage Site,[28] but Bamyan did not fully recover from the effects of the Mongol conquest for an extended period. Even decades later, sources indicate that the city remained largely uninhabited and in a state of ruin.[29]

After the victory, the Mongols plundered Tus and Mashhad, and by the spring of that year the Khorasan region was under their control.[30] Genghis Khan spent the summer in the foothills near Taloqan with his sons and armies, planning his next campaign against the Shah,[31] at which time he was joined by his sons Chagatai and Ögedei.[32] He then continued his march toward the Indian subcontinent.[33][34]

The Swedish historian Carl Fredrick Sverdrup estimated that only in the second half of 1221 did Genghis Khan finally gather around 50,000 troops to operate in Khorasan.[35] In addition, about 10,000 soldiers were with his generals Jebe and Subutai in the western Iranian Plateau, while several thousand others garrisoned Transoxiana or followed his son Jochi into the northern steppes.[36]

A common belief holds that after the local Afghan population was annihilated, Genghis Khan repopulated the region with Mongol soldiers and their slave women to garrison the area while he continued his campaign.[37] These settlers are believed to have become the ancestors of the Hazara people, whose name likely derives from the Persian hezār (“thousand”), referring to the Mongol military unit of one thousand soldiers.[38][39] Another theory proposes that they are descended from the ancient Kushan peoples.[40]

The death of Mutukan meant that his father Chagatai was eventually succeeded by his grandson Qara Hülegü as ruler of the Chagatai Khanate.[41]

References

editReferences

edit- ^ Kohn, George C (2007). Dictionary of Wars. New York : Facts on File/Checkmark Books. p. 55.

- ^ Sverdrup, Carl Fredrik (2017). The Mongol Conquests: The Military Operations of Genghis Khan and Sube'etei. p. 347. Retrieved 2025-04-23.

- ^ "City of Screams: Gholghola". Visit Bamiyan. 4 June 2020. Retrieved 2025-02-04.

- ^ Arends, Alfred Kárlovich (1946). Сборник летописей (Книга 2) (in Russian). Moscow: Institut vostokovedenii︠a︡ (Akademii︠a︡ nauk SSSR). p. 219.

- ^ Romano, Amy (2003). A Historical Atlas of Afghanistan. New York: The Rosen Publishing Group. p. 25.

- ^ Kohn, George Childs (2013). Dictionary of Wars. London: Routledge. p. 55.

- ^ Boyle, John Andrew (1958). The History of the World-Conqueror. Cambridge: Harvard University Press. p. 132.

- ^ Jaubert, Pierre-Amédée (1836). Géographie d'Edrisi (in French). Vol. I. Paris: Impr. royale. pp. 475–477.

- ^ Chandler, Tertius (1987). Four Thousand Years of Urban Growth: An Historical Census. Lewiston: St. David's University Press. p. 341.

- ^ Boyle, John Andrew (1958). The History of the World-Conqueror. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press. p. 132.

- ^ Boyle, John Andrew (1958). The History of the World-Conqueror. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press. p. 273.

- ^ Boyle, John Andrew (1958). The History of the World-Conqueror. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press. pp. 132–133.

- ^ Arends, Alfred Kárlovich (1946). Сборник летописей (Книга 2) (in Russian). Moscow: Institut vostokovedenii︠a︡, Akademi︠a︡ nauk SSSR. p. 219.

- ^ "City of Screams: Gholghola". Visit Bamiyan. 4 June 2020. Retrieved 2025-02-04.

- ^ Boyle, John Andrew (1958). The History of the World-Conqueror. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press. p. 132.

- ^ Sverdrup, Carl F. (2017). The Mongol Conquests: The Military Campaigns of Genghis Khan and Sübe'etei. Amherst: Helion & Company. p. 162.

- ^ Carnac, James R. (1838). The Shajrat Ul Atrak, or Genealogical Tree of the Turks and Tatars (PDF). London: W. M. H. Allen & Co. p. 173.

- ^ Arends, Alfred Kárlovich (1946). Сборник летописей (Книга 2) (in Russian). Moscow: Institut vostokovedenii︠a︡, Akademi︠a︡ nauk SSSR. p. 219.

- ^ Boyle, John Andrew (1958). The History of the World-Conqueror. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press. p. 133.

- ^ Arends, Alfred Kárlovich (1946). Сборник летописей (Книга 2) (in Russian). Moscow: Institut vostokovedenii︠a︡, Akademi︠a︡ nauk SSSR. pp. 219–220.

- ^ Arends, Alfred Kárlovich (1946). Сборник летописей (Книга 2) (in Russian). Moscow: Institut vostokovedenii︠a︡, Akademi︠a︡ nauk SSSR. p. 220.

- ^ Siddiqui, Muhammad Zubayr (1944). Saif bin Muhammad bin Yaqub Harvi: Ta'rīḵẖ-Nāma-yi-Harāt (in Persian). Calcutta: Gulshan. p. 50.

- ^ Majd, Ghulamreza Tabatabaʿi (2004). Tārīkhnāmeh ye Herāt (in Persian). Tehran: Ketabkhana Melli. p. 88.

- ^ Arends, Alfred Kárlovich (1946). Сборник летописей (Книга 2) (in Russian). Moscow: Institut vostokovedenii︠a︡, Akademi︠a︡ nauk SSSR. p. 219.

- ^ Boyle, John Andrew (1958). The History of the World-Conqueror. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press. p. 133.

- ^ Romano, Amy (2003). A Historical Atlas of Afghanistan. New York: The Rosen Publishing Group. p. 25.

- ^ Kohn, George Childs (2013). Dictionary of Wars. London: Routledge. p. 55.

- ^ "Cultural Landscape and Archaeological Remains of the Bamiyan Valley". UNESCO World Heritage Centre. Archived from the original on 28 January 2007. Retrieved 2 August 2022.

- ^ Foundation, Encyclopaedia Iranica. "Welcome to Encyclopaedia Iranica". iranicaonline.org. Retrieved 2021-08-14.

- ^ Chamakhi, Mustapha Kameleddine (2021). Islam in All Its States. Paris: BoD – Books on Demand. p. 122.

- ^ Arends, Alfred Kárlovich (1946). Сборник летописей (Книга 2) (in Russian). Moscow: Institut vostokovedenii︠a︡, Akademi︠a︡ nauk SSSR. p. 220.

- ^ Sverdrup, Carl F. (2017). The Mongol Conquests: The Military Campaigns of Genghis Khan and Sübe'etei. Amherst: Helion & Company. p. 162.

- ^ Kohn, George Childs (2013). Dictionary of Wars. London: Routledge. p. 55.

- ^ Ratchnevsky, Paul (1991). Genghis Khan: His Life and Legacy. Oxford: Blackwell. p. 164.

- ^ Sverdrup, Carl F. (2017). The Mongol Conquests: The Military Campaigns of Genghis Khan and Sübe'etei. Amherst: Helion & Company. p. 113.

- ^ Sverdrup, Carl F. (2010). John France; Clifford J. Rogers; Kelly DeVries (eds.). Journal of Medieval Military History. Vol. VIII. Martlesham: Boydell and Brewer. p. 113.

- ^ Minahan, James B. (2014). Ethnic Groups of North, East, and Central Asia: An Encyclopedia. Santa Barbara: ABC-CLIO. p. 99.

- ^ Ratchnevsky, Paul (1991). Genghis Khan: His Life and Legacy. Oxford: Blackwell. p. 164.

- ^ Metcalfe, Daniel (2009). Out of Steppe: The Lost Peoples of Central Asia. London: Hutchinson. p. 168.

- ^ Minahan, James B. (2014). Ethnic Groups of North, East, and Central Asia: An Encyclopedia. Santa Barbara: ABC-CLIO. p. 99.

- ^ Adshead, S. A. M. (2016). Central Asia in World History. New York: Palgrave Macmillan. p. 83.

Notes

edit- ^ Also transliterated as Mao-Tukan, Mutugen, Muatukan, Mütegin, Metiken, Mamgan, or Mamusgan.