Machine learning–based model for predicting distant lymph node metastasis in esophageal cancer

Highlight box

Key findings

• The machine learning models developed in this study could accurately predict distant lymph node metastasis (LNM) in esophageal cancer. Among the seven constructed machine learning models, the gradient boosting (GB) model outperformed the other models, with an accuracy of 0.929, a recall of 0.427, an F1 score of 0.414, and an area under the curve of 0.912.

What is known and what is new?

• The 5-year survival rate of patients with esophageal cancer is generally poor, and a critical prognostic parameter affecting patient survival is the presence or absence of LNM. Moreover, distant lymphatic metastases are more difficult to detect than are local metastases.

• The interpretable module in our study identified the key predictors that affect the predictive power of the model, which included tumor (T) stage, liver metastasis, lung metastasis, node (N) stage, age, histologic type in the International Classification of Diseases for Oncology, third edition. Our study is the first to establish a machine learning model for distant LNM in esophageal cancer using clinical data, with GB outperforming the other algorithms.

What is the implication, and what should change now?

• The GB model showed robust performance and may aid clinicians in the initial assessment of distant LNM in patients with esophageal cancer. Future research should further refine and improve the model through incorporation of large-scale, multicenter, real-world data.

Introduction

According to Global Cancer Observatory (GLOBOCAN) 2022, the number of new cases of esophageal cancer worldwide in 2022 was 511,000—placing it 11th in incidence among cancers—and the number of related deaths was 445,000—placing it 7th in mortality rate (1). Approximately 50% of patients with esophageal cancer have distant metastases at the time of initial diagnosis, and more than one-third of patients develop distant metastases after surgery or radiotherapy. In Europe and the United States, esophageal adenocarcinoma is the predominant pathologic type, whereas the predominant pathologic type in Asia, Africa, South America, and the African American population in North America is squamous cell carcinoma (2).

The esophagus is located in the neck and is surrounded by numerous blood vessels and lymph nodes; thus, the tumor spreads rapidly and metastasizes to the whole body through blood vessels and lymphatic vessels (3). A portion of tumors also directly metastasize to nearby normal tissues via three routes: hematogenous metastasis, lymphatic metastasis, and direct diffusion. Lymph node metastasis (LNM) can be categorized into regional LNM and distant LNM. Regional LNM involves the metastasis of tumor cells to lymph nodes in the drainage area near the primary site [node (N) stage]. Meanwhile, distant LNM involves tumor metastasis to distal lymph nodes beyond the drainage area of the primary site and is usually classified as distant metastasis or locally advanced.

The presence and number of lymph node metastases are the most relevant prognostic factors in esophageal cancer and are independent predictors of long-term survival. The location of metastatic lymph nodes depends on tumor histology, primary tumor location, tumor (T) stage, and neoadjuvant therapy (4). Locoregional nodal metastasis (N stage) refers to LNM within the drainage area of the primary focus (e.g., mediastinal or peripancreatic lymph nodes in thoracic esophageal cancer) and is commonly treated by surgery combined with radiotherapy for radical cure. Distant nodal metastasis refers to LNM beyond the conventional drainage, and its stage depends on the histologic type. In squamous carcinoma, supraclavicular or celiac trunk LNM is defined as M1 (distant metastasis). Distant solid organ metastasis (M1) refers to non-lymph node organ metastases, such as those in the liver and lung. The target of distant node metastasis is the lymph nodes beyond the regional drainage area, and the route of metastasis involves abnormal lymphatic drainage or skip metastasis. The dense lymphatic network and vascular structure around the esophagus contribute to the multidirectional spread of the tumor to the abdomen, mediastinum, and neck, with skip metastasis being particularly common. This makes it difficult to standardize the extent of radiotherapy and lymph node dissection in the treatment of patients with esophageal cancer.

In addition, distant lymphatic metastases are more difficult to detect than local metastases, and thus it is necessary to establish appropriate predictive models to make predictions regarding distant lymph node metastases to guide diagnosis and subsequent therapeutic measures.

In machine learning, computers “learn” from data without explicit programming instructions, through which they can formulate predictions or decisions on the basis of learned patterns (5). Machine learning algorithms can handle a large amount of high-dimensional and diverse data, including clinical data such as age, sex, and tumor stage. Effective features can be extracted from these data to significantly improve the prediction accuracy. In this study, we used the demographic and clinicopathological data of patients diagnosed with esophageal cancer from the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) database to construct seven machine learning models for the prediction of distant LNM. Specifically, we aimed to predict distant nodal metastasis in patients with esophageal cancer lacking solid organ M1 disease, and the model with the best performance was validated in a validation set. It is hoped that the use of this model can aid in clinical diagnosis and inform subsequent steps in treatment. We present this article in accordance with the TRIPOD reporting checklist (available at https://jtd.amegroups.com/article/view/10.21037/jtd-2025-484/rc).

Methods

Study population

Retrospective analyses were performed on the SEER database (http://seer.cancer.gov), which is a large public health database created and maintained by the National Cancer Institute (NCI) to provide epidemiologic information on cancer. The database contains information on patients with cancer across multiple regions of the United States, includes approximately 34% of the US population across multiple racial groups, and provides long-term surveillance of cancer incidence, treatment, and prognosis. Thus, the SEER database data is broadly representative for use in cancer epidemiologic studies.

SEER*stat 8.4.4 software (NCI, Bethesda, MD, USA) was used in this study to retrieve data from the SEER database,17 registries, November 2023 (2000–2021). Our study extracted the information from patients with esophageal cancer, specifically squamous cell carcinoma and adenocarcinoma, whose tumor site and morphology were coded according to the 2023 International Classification of Diseases for Oncology, third edition (ICD-O-3), from 2010 to 2021. This study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and its subsequent amendments.

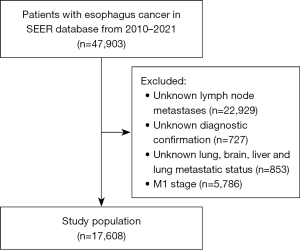

The exclusion criteria were as follows: (I) unknown lymph node metastases (i.e., whether it was present or not); (II) missing diagnostic confirmation; (III) unknown status for lung, brain, liver, or lung metastasis status; and (IV) M1 stage disease.

Data selection

In this study, the clinicopathological and demographic characteristics of patients were selected for analysis, including age; recoded, adapted classification scheme for tumors of adolescents and young adults (AYA) site, ICD-O-3 histologic type, recoded chemotherapy status, recoded radiotherapy status, T stage, N stage, bone metastasis, liver metastasis, brain metastasis, and lung metastasis. The histological types of esophageal cancer were classified according to the ICD-O-3 as 8070/3 (squamous cell carcinoma), 8010/3 (carcinoma), 8140/3 (adenocarcinoma), and 8000/3 (neoplasm). All patients with esophageal cancer were staged according to the American Joint Committee on Cancer (AJCC) eighth edition guidelines and SEER staging information.

Data preprocessing and feature engineering

The data we collected from the SEER database included demographic and clinical characteristics.

The variables included age, sex, T stage, N stage, histologic type, recoded chemotherapy status, recoded radiotherapy status, bone metastasis, liver metastasis, brain metastasis, lung metastasis, marital status, median household income, etc. Univariate and multivariate logistic regression analyses were performed via GraphPad Prism (Dotmatics, Boston, MA, USA; https://www.graphpad.com/) to select the variables incorporated by machine learning. The main purpose of univariate logistic regression is to assess the effect of a given independent variable on the target binary variable and to determine whether that independent variable is significantly correlated with the target variable. The main purpose of multivariate logistic regression is to analyze how multiple independent variables interact to affect the dependent variable and to assess the independent effect of each independent variable on the dependent variable while controlling for the others. This can help identify which factors have a significant effect on the predicted outcome (6).

Model establishment and evaluation

The development dataset consisted of cases collected from 2010 to 2021, which were divided into training and validation cohorts at an 8:2 ratio. Our predicted outcome variable was the presence of distant lymph node metastases, a bivariate predictor of clinical outcome. We used the Jupyter Notebook to construct seven machine learning models, including random forest (RF), decision tree (DT), extreme gradient boosting (XGBoost), gradient boosting (GB), Naïve Bayes, artificial neural network (ANN), and adaptive boosting (ADB). To increase model effectiveness and reduce the risk of overfitting, all the models use grid search during training. For the missing data, we used the mean method to impute missing values. To address category imbalance, we used the synthetic minority oversampling technique (SMOTE) for data balancing. SMOTE is a data augmentation method for solving the problem of category imbalance in classification tasks. It improves the model’s ability to recognize minority classes by generating synthetic samples to increase the number of minority class samples. We validated the machine learning model with data from 53 patients at the Beijing Friendship Hospital. For the validation set, we chose to incorporate the same clinical factors as those in the training set in predicting distant LNM. To ensure that the model was free from subjective bias, we removed the patient ID when building the model.

RF is an integrated learning method that involves bootstrap aggregating. Combining multiple DTs improves the accuracy and stability of a model (7). RF is based on DTs but reduces overfitting and enhances generalization through diversity (i.e., each tree uses a different subset of data and features). Multiple DTs are constructed via a random sampling of the training data (with bootstrap sampling), and each tree is trained with only a portion of the data, which reduces the variance of the model. At the split of each node, instead all the features being used to find the optimal split feature, a subset of features is randomly selected from the feature set. This increases the diversity among the trees and prevents overfitting. In integrated decision-making, each tree generates a prediction, and in classification problems, majority voting is used to determine the final category.

Each tree in a classification problem produces a prediction category, and the final prediction category is the result of a majority vote of all tree predictions. The formula is as follows:

where T is the number of DTs, and is the class i tree’s prediction class for sample x.

DT is a classical supervised learning algorithm that can be used for classification and regression problems. It classifies data into categories or values through a series of decision rules to help make predictions (8). The advantage of a DT is that it is easy to understand and interpret, and it represents the decision-making process through a tree structure. A DT divides a dataset into subsets by recursively partitioning the dataset until the samples within each subset belong to the same category; each internal node represents a test of a feature, each branch represents a different choice of test results, and each leaf node represents the final prediction.

XGBoost belongs to the boosting class of algorithms, and its core strategy is to combine multiple weak learners (usually DTs) into a single strong learner via iterative means. Each iteration attempts to fit the previous iteration’s residuals (error portion), thus continuously improving the model’s prediction accuracy (9). In the GB framework, the goal is to train the model via multiple iterations, where each iteration minimizes the residual (error), which is the prediction error of the previous round of the model. In each round of iterations, a new base learner (usually a tree) is added to the existing model through an additive model, and the overall goal of the model is to minimize the objective function (usually the loss function).

The objective of XGBoost is to minimize a loss function with a regularization term to prevent overfitting. The objective function is given by the following:

where T is the number of leaf points of the tree, γ is a parameter that controls the complexity of the tree, and λ is the L2 regularization coefficient that is used to control the complexity during tree splitting and prevent model overfitting.

GB is an integrated learning method used to improve prediction accuracy by combining multiple weak learners (usually DT) into one strong learner (10). It is a type of boosting method that reduces bias and improves model accuracy by combining multiple weak learners. GB optimizes the model incrementally by means of gradient descent so that each new learner is able to specifically correct the errors of the previous round of the model.

The Naïve Bayes model is a simple probabilistic classification algorithm based on Bayes’ theorem. It is particularly well-suited for classification problems and excels when dealing with large-scale data. The core principle is based on Bayes’ theorem, which involves calculating the probability that a sample belongs to each category given a set of features and ultimately choosing the category with the highest probability as the prediction. The key assumption of Naïve Bayes is that the features are independent of one another (11); that is, the associations between features are ignored when the categories are known. On the basis of this assumption, Naïve Bayes simplifies the computation by decomposing the joint probability of multiple features into the product of the independent probabilities of each feature.

ANNs are a class of mathematical models inspired by the biological nervous system. ANNs consist of multiple nodes (or “neurons”), and the weights connecting them to learn the relationship between input data and target outputs through the computation of input data and neurons (12). They learn the relationship between the input data and the target output through computations between the input data and the neurons. ANNs are usually composed of the following basic components: an input layer, a hidden layer, an output layer, connection weights, and an activation function.

Adaptive boosting (AdaBoost) is a boosting algorithm for integrated learning that combines multiple weak learners to obtain a more accurate (high accuracy) and robust (strong generalization ability) supervised model. The algorithm works by training multiple weak classifiers, assigning weights to each of them, and then combining the weak classifiers through an additive model into a final strong classifier that classifies the samples (13).

Machine learning evaluation metrics

We used various evaluation metrics, including accuracy, recall, F1 score, confusion matrix, and the area under the receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve (AUC), to assess the models. The confusion matrix is a tool for evaluating the performance of a classification model that identifies the categories on which the model performs poorly so that model performance can be optimized through the adjustment of the model parameters, selection of different features, or improvement of the algorithm. A confusion matrix specifies the number of true positives (TPs)—samples that the model correctly predicts as positive classes—true negatives (TNs)—samples correctly predicted to be negative—false positives (FPs)—samples which the model incorrectly predicted as negative but which are positive—and false negatives (FNs)—samples which the model incorrectly predicted as positive but which are negative (14). The accuracy indicates the percentage of correctly predicted cases out of the total number of cases according to the following formula: accuracy = (TP + TN)/(TP + TN + FP + FN). The recall indicates the proportion of cases that are actually positive and that are correctly predicted and is calculated as follows: recall = TP/(TP + FN). The F1 score indicates the proportion of cases that are actually positive that are correctly predicted, and is calculated as follows: F1 score = 2 × precision × recall/(precision + recall).

The interpretable module

The interpretable module for machine learning is designed to help users understand and explain the decision-making process of machine learning models and their outputs. It thus plays an important role in overcoming the “black-box effect” of clinical predictions, rendering them acceptable to clinicians. Shapley additive explanation (SHAP) analysis is a method used to interpret the prediction results of machine learning models. It is based on Shapley values (a concept from game theory) and used to measure the contribution of each feature to the model’s prediction results (15). We identified the key predictors that affect the predictive power of the model through SHAP analysis.

Evaluation of distant metastases

Esophageal cancer is a cancer that is highly dependent on the lymphatic system for metastasis, and there is a relationship between lymphatic metastasis and bone metastasis, lung metastasis, brain metastasis, and liver metastasis. We compared the survival of patients with different metastases via Kaplan-Meier curves and analyzed survival under different treatment modalities in subgroups. Survival curves were plotted using the Kaplan-Meier method. We used Kaplan-Meier Fitter to plot survival curves for patients with distant lymph node metastases and lung, liver, bone, and brain metastases. A statistical test was subsequently used to compare the survival curves of two or more groups of survival data for significant differences; if the P value was less than 0.05, it was concluded that there was a significant difference in the survival curves between the two groups, indicating that there was a statistically significant difference in the survival of patients with different types of metastases.

Statistical analysis

Categorical variables are expressed as the frequency (percentage). Survival analysis was conducted via Kaplan-Meier curves and the log-rank test. A statistical test was subsequently used to compare the survival curves of two or more groups of survival data for significant differences; if the P value was less than 0.05, it indicated that there was a statistically significant difference in the survival of patients with different types of metastases. A two-tailed P value <0.05 was considered statistically significant. All the statistical analyses were performed via Python 3.8 (Python Software Foundation, Wilmington, DE, USA) and R studio version 4.3.1 (http://www.r-project.org/).

Results

Clinical characteristics of patients

A total of 17608 patients were included in this study after we excluded those with unknown LNM status (n=22,929); unknown diagnostic confirmation (n=727); unknown lung, brain, liver, or lung metastatic status (n=853); and M1 stage (n=5,786) (Figure 1). The included patients were divided into a training set (n=14,086) and a test set (n=3,522) at a ratio of 8:2. The detailed baseline characteristics of the patients are listed in Table 1. We collected data on age, T stage, N stage, liver metastasis, brain metastasis, lung metastasis, bone metastasis, and AYA site status. The majority of the patients who were diagnosed with esophageal cancer were between 60 and 80 years old (n=10,924; 62.04%). The next most common age group was those older than 80 years (n=4,828; 27.42%). Among the patients younger than 60 years, 1,856 accounted for 10.54% of the majority. Among the study population, 1,856 patients (10.54%) were younger than 60 years. The most common stage of esophageal cancer was T3 stage (n=3,612; 20.51%), followed by T1 (n=3,176; 18.04%) and T4 (n=709; 4.03%). The most common N stage was N0 (n=4,900; 27.83%), and the most common metastasis (M) stage was M0 (n=10,005; 56.82%). Liver metastasis was the most common type of metastasis (n=1,184; 6.72%), followed by metastasis of the lung (n=721; 4.09%) and bone and brain (n=141; 0.80%). For the validation set, we selected the same clinical factors for inclusion as those in the training set.

Table 1

| Variable | Training set (n=14,086), n (%) | Test set (n=3,522), n (%) | Total (n=17,608), n (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age, years | |||

| <60 | 1,479 (10.50) | 377 (10.70) | 1,856 (10.54) |

| 60–80 | 8,707 (61.81) | 2,217 (62.95) | 10,924 (62.04) |

| >80 | 3,900 (27.69) | 928 (26.35) | 4,828 (27.42) |

| T stage | |||

| T1 | 2,023 (14.36) | 1,153 (32.74) | 3,176 (18.04) |

| T2 | 753 (5.35) | 431 (12.24) | 1,184 (6.72) |

| T3 | 2,443 (17.34) | 1,169 (33.19) | 3,612 (20.51) |

| T4 | 482 (3.42) | 227 (6.45) | 709 (4.03) |

| Others/unknown | 8,385 (59.53) | 542 (15.39) | 8,927 (50.70) |

| N stage | |||

| N0 | 3,175 (22.54) | 1,725 (48.98) | 4,900 (27.83) |

| N1 | 2,778 (19.72) | 1,442 (40.37) | 4,220 (23.97) |

| N2 | 165 (1.17) | 76 (2.16) | 241 (1.37) |

| N3 | 67 (0.48) | 35 (0.99) | 102 (0.58) |

| Others/unknown | 7,901 (56.09) | 244 (6.93) | 8,145 (46.26) |

| M stage | |||

| M0 | 8,196 (58.19) | 1,809 (51.36) | 10,005 (56.82) |

| Unknown | 5,890 (41.81) | 1,713 (48.63) | 7,603 (43.18) |

| Liver metastasis | |||

| Yes | 1,184 (8.41) | – | 1184 (6.72) |

| No | 12,901 (91.58) | 3,522 (100.0) | 16,423 (93.27) |

| Unknown | 1 (0.007) | – | 1 (0.005) |

| Brain metastasis | |||

| Yes | 141 (1.88) | – | 141 (0.80) |

| No | 13,944 (98.12) | 3,522 (100.0) | 17,466 (99.19) |

| Unknown | 1 (0.007) | – | 1 (0.005) |

| Lung metastasis | |||

| Yes | 721 (5.12) | – | 721 (4.09) |

| No | 13,364 (94.87) | 3,522 (100.0) | 16,886 (95.90) |

| Unknown | 1 (0.007) | – | 1 (0.005) |

| Bone metastasis | |||

| Yes | 662 (4.70) | – | 662 (3.76) |

| No | 13,423 (95.29) | 3,522 (100.0) | 16,945 (96.23) |

| Unknown | 1 (0.007) | – | 1 (0.005) |

| Recoded AYA site | |||

| Carcinoma of the esophagus | 13,924 (98.85) | 3,444 (97.79) | 17,368 (98.64) |

| Malignant neoplasms | 127 (0.90) | 28 (0.80) | 155 (0.88) |

| Others/unknown | 35 (0.25) | 50 (1.42) | 85 (0.48) |

AYA, adolescents and young adults; M, metastasis; N, node; T, tumor.

Univariate and multivariate logistic regression analyses

Univariate and multivariate logistic regression analyses were used to identify risk factors associated with patients with esophageal cancer and distant LNM. In the univariate logistic regression analysis, the significant factors identified included age [95% confidence interval (CI): 0.9739–0.9806; P<0.001], AYA site recorded in the 2020 revision (95% CI: 0.4046–0.8463; P=0.007), ICD-O-3 histologic type (95% CI: 1.000–1.001; P=0.002), radiotherapy status (95% CI: 0.6196–0.7063; P<0.001), chemotherapy status (95% CI: 1.038–1.220; P=0.004), bone metastasis (95% CI: 4.518–5.510; P<0.001), brain metastasis (95% CI 2.223–3.103; P<0.001), liver metastasis (95% CI: 3.951–4.647; P<0.001), and lung metastasis (95% CI: 4.125–4.920; P<0.001). In the multivariate logistic regression analiys, the significant factors identified included age (95% CI: 0.9824–0.9904; P<0.001), AYA site (95% CI: 0.3728–0.8464; P=0.009), ICD-O-3 histologic type (95% CI: 1.001–1.002; P<0.001), T stage (95% CI: 0.9253–0.9993; P=0.046), N stage (95% CI: 4.130–4.847; P<0.001), radiotherapy status (95% CI: 0.7480–0.8571; P<0.001), bone metastasis (95% CI: 1.838–2.307; P<0.001), liver metastasis (95% CI: 1.409–1.714; P<0.001), brain metastasis (95% CI: 1.062–1.563; P=0.008), lung metastasis (95% CI: 1.982–2.425; P<0.001), and total number of in situ/malignant tumors (95% CI: 0.7478–0.8826; P<0.001). As a result, we included 10 features as machine learning variables: age, histologic type, ICD-O-3 histologic type, T stage, N stage, radiotherapy status, bone metastasis, liver metastasis, lung metastasis, brain metastasis, and total number of in situ/malignant tumors.

Model performance

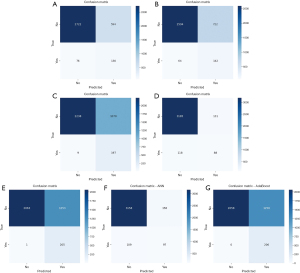

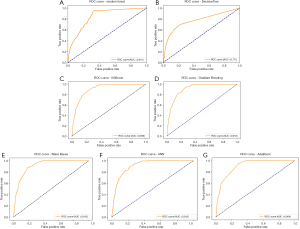

The development dataset consisted of cases collected from 2010 to 2021, which were divided into training and validation cohorts at an 8:2 ratio. We used GridSearchCV for the parameter search for optimal parameter exploration.GridSearchCV is a hyperparameter tuning method and tool available in the Python machine learning library scikit-learn. On the basis of the independent predictive variables identified through univariate and multivariate logistic regression, we used the Jupyter Notebook to build machine learning models, including the RF, DT, XGBoost, GB, Naïve Bayes, ANN, and AdaBoost models. The model metrics included accuracy, recall, F1 score, and AUC. The performance of the seven machine learning models is summarized in Table 2. The overall performance of the prediction models in the training set was good. The confusion matrix is shown in Figure 2, and the ROC curves are shown in Figure 3. The results revealed that GB had the best performance, with an accuracy of 0.929, a recall of 0.427, an F1 score of 0.414, and an AUC of 0.912. The RF model provided balanced performance, with a reasonable accuracy of 0.810, a moderate recall of 0.631, and a competitive AUC of 0.841; meanwhile, the DT model showed a slightly lower accuracy of 0.777 but an improved recall of 0.689 at the cost of a reduced AUC of 0.771. AdaBoost and Naïve Bayes achieved near-perfect recalls of 1.000 and 0.995, respectively, but their low F1 scores (0.247 and 0.246, respectively) and suboptimal accuracies (0.643 and 0.644, respectively) imply poor precision, likely due to high FP rates. XGBoost exhibited a similar trade-off, with exceptional recall (0.956) and a high AUC (0.909) but low accuracy (0.691) and F1 score (0.266). Notably, ANN and GB achieved the highest F1 scores (0.421 and 0.414, respectively), reflecting a better balance between precision and recall. These results suggest that model selection should depend on the specific task priorities: GB or ANN for high overall accuracy, AdaBoost or Naïve Bayes for maximal sensitivity (despite low precision), and RF for a balanced approach.

Table 2

| Model | Accuracy | Recall | F1 score | AUC |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Random forest | 0.810 | 0.631 | 0.280 | 0.841 |

| Decision tree | 0.777 | 0.689 | 0.265 | 0.771 |

| XGBoost | 0.691 | 0.956 | 0.266 | 0.909 |

| Gradient boosting | 0.929 | 0.427 | 0.414 | 0.912 |

| Naïve Bayes | 0.644 | 0.995 | 0.246 | 0.913 |

| ANN | 0.924 | 0.471 | 0.421 | 0.912 |

| AdaBoost | 0.643 | 1.000 | 0.247 | 0.904 |

AdaBoost, adaptive boosting; ANN, artificial neural network; AUC, area under the curve; XGBoost, extreme gradient boosting.

For the validation set, we used a dataset from our clinical center, Beijing Friendship Hospital, which included 53 patients with esophageal cancer. The ROC curve revealed that the GB model had the highest AUC of 0.857, indicating the best performance in distinguishing between positive and negative samples. Moreover, it had a high accuracy of 0.818, a recall of 0.857, and an F1 score of 0.857. The validation set showed good classification performance for GB.

Overall, the GB and ANN methods performed well in terms of accuracy, especially the GB method, which was more prominent in terms of the AUC and precision. AdaBoost is a good choice when there is a high demand for recall, as it captures more positive class samples despite having a lower accuracy.

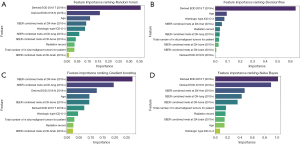

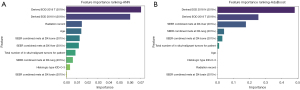

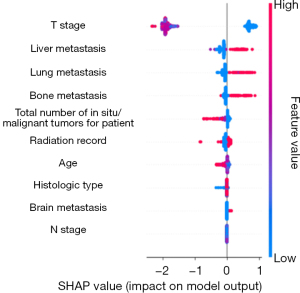

The interpretable module

The feature importance ranking revealed the top 10 variables with the best performance in predicting distant LNM. The factors incorporated in the GB model for patients with esophageal cancer included liver metastasis, lung metastasis, N stage, age, bone metastasis, T stage, ICD-O-3 histologic type, total number of in situ/malignant tumors, radiotherapy status, and brain metastasis (Figures 4,5). For the XGBoost model, the Shapley analysis revealed that the top five variables included T stage, liver metastasis, lung metastasis, bone metastasis, and the total number of in situ/malignant tumors (Figure 6). In the RF model, T stage, N stage, and age were the three most influential factors. Similarly, for the DT model, T stage, age, and ICD-O-3 histologic type were deemed highly important. In the Naïve Bayes model, the most important factors were T stage, N stage, and age; for the AdaBoost model, they were N stage, T stage, and liver metastasis; and for the ANN model, they were T stage, N stage, and radiotherapy status. The results indicated that T stage had the greatest importance in all models except for the GB model. The prediction of distant LNM can be aided by the appropriate selection of interpretable clinical predictive variables for physicians.

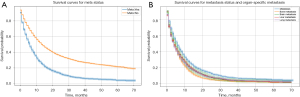

Evaluation of distant metastases

As shown in Figure 7, patients who developed distant lymph node metastases had a worse prognosis. The P value of the log-rank test comparing distant LNM and lung metastasis was 3.12e−15 (P<0.05), and the test statistic was 62.18993, indicating a significant difference in survival curves. The P value of the log-rank test comparing distant LNM and bone metastasis was 3.40e−25 (P<0.05), and the test statistic was 107.53272. The results revealed a significant difference in survival curves. Moreover, the P values of the log-rank test for comparing distant LNM with liver metastasis and brain metastasis were 1.55466e−15 and 3.06967e−04, respectively, indicating a significant difference in survival curves. Furthermore, we compared the correlations between the liver, lung, bone, and brain. The results revealed significant differences in survival curves for lung and bone metastases (P=2.07e−02), bone and liver metastases (P=4.20e−01), and bone and brain metastases (P=4.34e−04).

Discussion

Esophageal cancer is a common malignant tumor worldwide and is highly lethal, with the 5-year survival rate of patients being generally low (16). Distant LNM of esophageal cancer is associated with a poor prognosis, and so predictive modeling of metastasis is necessary. Lymph node skip metastasis is a common form of lymphatic metastasis in patients with esophageal cancer and is defined as distant LNM arising without the involvement of lymph nodes at more proximal sites (17).

Lymph nodes are part of the body’s immune system and one of the common pathways in which tumor cells spread. Cancer cells typically spread from the primary tumor to adjacent lymph nodes through the lymphatic system, which in turn may continue to spread to distant lymph nodes and other organs through the lymphatic vessels or bloodstream. The presence or absence of distant LNM in patients with esophageal cancer is important for therapeutic decisions and prognosis. Predicting whether a cancer will cause distant LNM (distant N) or, in other words, spread to distant lymph nodes beyond regional drainage, is highly important in clinical oncology. The prognosis of patients with distant lymph node metastases is usually intermediate between that of patients with regional lymph node metastases (N1–2) and those with distant organ metastases (M1), and the status of distant LNM can be used for more precise prognostic stratification. This can aid in avoiding under- or overtreatment. Undertreatment can occur if distant lymph node metastases are misclassified as regional lymph node metastases. Misclassification as distant organ metastases may cause patients to miss out on potentially curative treatment. Therefore, identifying high-risk factors for esophageal cancer and accurately predicting the likelihood of distant LNM on the basis of clinical and pathologic features are crucial for sound clinical decision-making.

Imaging is the most common method for determining distant LNM. Commonly used imaging methods include positron emission tomography–computed tomography (PET/CT), CT, magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), and ultrasound (18). PET/CT is currently the most commonly used method for determining distant LNM in the image area. It detects the metabolic activity of tumor cells by labeling them with a radioactive tracer [e.g., 18F-fluorodeoxyglucose (18F-FDG)], regardless of whether their size exceeds the criteria for imaging visualization (19). However, FPs (increased lymph node metabolism due to inflammation or infection) or TNs (small metastases or low-metabolism tumors that are undetectable) may still occur. In addition, certain benign conditions, such as tuberculosis and inflammation, may cause altered metabolic activity, leading to misdiagnosis. Routine CT scans can help detect enlarged lymph nodes, especially lymph node metastases, in areas such as the abdomen and mediastinum. However, the sensitivity for detecting small distant lymph node metastases is poor, especially if the tumor is small or if the lymph nodes are only mildly enlarged (20). MRI is generally unsuitable for identifying lung and bone metastases. Moreover, liquid biopsy (via circulating tumor DNA and circulating tumor cells) methods may also yield FPs and FNs, and more clinical validation of their sensitivity and specificity for different cancers is still required. Therefore, the development of novel techniques for predicting distant LNM is urgently needed.

Machine learning can discover patterns and relationships in data by building mathematical models and making predictions, classifications, or decisions on the basis of these patterns. Machine learning is being increasingly used in medical data analysis and disease prediction, especially in determining cancer, including LNM. A previous study of patients with hepatocellular carcinoma in which a machine learning model was built to predict distant LNM and prognostic outcomes revealed the clinical importance of high-risk LNM (21). Interpretable machine learning allows physicians to understand how a model arrives at a prediction, which increases trust in the model’s results and mitigates the “black box” problem. It also identifies key factors that influence clinical outcomes, and physicians can use these features to optimize treatment plans and make more accurate diagnoses and interventions. In our study, we examined data from the SEER database to identify the independent high-risk factors associated with lung metastasis through logistic regression analysis. This approach effectively mitigates the statistical errors caused by small sample sizes. Specifically, we included 10 features as machine learning variables: age, histologic type, ICD-O-3, T stage, N stage, recoded radiotherapy status, bone metastasis, liver metastasis, lung metastasis, brain metastasis, and total number of in situ/malignant tumors.

Wang et al. analyzed risk factors for LNM and developed a nomogram to predict LNM risk in patients with superficial esophageal squamous cell carcinoma (SESCC) (22). The nomogram, which included six variables, showed good discrimination, with an AUC of 0.789 (95% CI: 0.737–0.841) in the training set and 0.827 (95% CI: 0.755–0.899) in the validation set. Chen et al. developed three nomogram models to predict the likelihood of LNM, distant metastasis, and prognosis in patients with early esophageal cancer (23). The AUCs of LNM and distant metastasis nomograms were 0.668 and 0.807, respectively. The corresponding concordance index of the overall survival (OS) nomogram was 0.752. The classification performance of the nomogram was unsatisfactory, and its accuracy needs to be further improved.

Huang et al. reported positive lymph node ratio (PLNR) to be an independent prognostic factor for predicting postoperative distant metastasis and prognosis in patients with esophageal squamous cell carcinoma (ESCC) and found that patients with a PLNR ≤0.15 had a longer OS (24). Another study found that tumor size, macroscopic type of tumor, degree of differentiation, depth of tumor invasion, and lymphovascular invasion were factors associated with LNM in patients with SESCC (25). Understanding LNM status could aid in determining whether patients with SESCC can be cured by endoscopic resection, without the need for additional esophagectomy. The accurate prediction of LNM is crucial for determining appropriate treatment strategies for SESCC, particularly in selecting candidates for endoscopic resection. While several studies have attempted to develop predictive models, their performance has varied considerably. It is necessary to develop more accurate clinical prediction models for adjuvant therapy.

In our study, GB was the best-performing model, surpassing the other models in several evaluation metrics, especially in terms of accuracy and AUC. It was able to distinguish between positive and negative samples better and performed well in distinguishing between different categories. The model accurately forecasted the risk of distant LNM in patients by considering a diverse clinical indicator. This predictive tool can be used to inform clinical diagnosis and treatment, thus aiding clinicians in decision-making. The validation included a dataset consisting of 53 patients in our clinical center and indicated good classification performance, with an ROC curve of 0.8517. The core aim of this study was to optimize the identification of positive cases of cancer metastasis. Recall implies that the model captures all TP cases, which is critical for early clinical diagnosis, so we did not include precision as an assessment metric. After adjustments were made to the model parameters, the GB model fully met the clinical needs, according to the core metrics of recall and AUC, demonstrating the best balance.

In the interpretable module, T stage, N stage, age, liver metastasis, and lung metastasis significantly varied with machine learning prediction. Esophageal cancer cells spread to neighboring lymph nodes through lymphatic vessels, and as the cancer progresses further, the cancer cells may break through the barrier of local lymph nodes and enter larger lymphatic vessels or the blood system, thus achieving distant metastasis. The T stage reflects the size of the primary esophageal cancer tumor, the degree of local invasion, and the impact on adjacent structures. A higher T stage (stages T3 and T4) usually implies that the tumor has become more aggressive and is prone to spreading through the lymphatic vessels or bloodstream, which increases the risk of distant LNM. Therefore, the T stage provides important clues for predicting distant LNM, especially when the local extension of the tumor is more extensive and when the risk of distant metastasis is significantly increased (26). Meanwhile, the N stage reflects the degree of local spread of cancer, especially the degree of local LNM, which directly affects the possibility of cancer cell metastasis to distant lymph nodes (27). The higher the N stage is, the more extensive the spread of cancer cells in the body. Local LNM in esophageal cancer is often a precursor of systemic metastasis. When cancer cells break through the barrier of local lymph nodes and metastasize to multiple lymph nodes, there is a greater chance for cancer cells to enter the whole body through lymphatic vessels or blood, which may lead to metastasis to distant lymph nodes or other organs. Therefore, the higher the N stage is, the greater the risk of distant LNM. Age is also an important predictor of distant LNM, which may be related to immune senescence; as we age, immune system function decreases, leading to a decreased ability to monitor and clear tumor cells, which may promote the spread of cancer cells to distant lymph nodes. Liver metastasis is an important sign that cancer has spread throughout the body, and it usually indicates that the cancer is at an advanced stage and has spread to other distant organs and lymph nodes through the blood system. The occurrence of liver metastasis often indicates that cancer cells has the ability to metastasize widely and is often accompanied by distant LNM (28). Therefore, liver metastasis is not only an important sign of the systemic spread of cancer but also suggests the risk of distant LNM, which indicates increased difficulty in treatment and poor prognosis. Lung metastasis usually indicates that cancer cells have a strong ability to spread. Most tumors are confined to the primary site or local lymph nodes in the early stages; however, as the tumor progresses, the cancer cells spread to distant organs, including the lungs, through the blood or lymphatic system. The lung is an organ with abundant blood flow, so it is usually the first “receiving station” for cancer cells to metastasize to distant sites. By the time lung metastasis occurs, cancer cells may have already spread through the bloodstream to other organs, including distant lymph nodes. As a result, distant LNM is a sign of the systemic spread of cancer, reflecting the highly invasive and spreading ability of cancer cells, and often occurs in advanced stages of cancer. Therefore, the T, M, and N stages of the tumor and its ability to metastasize to other organs can be predicted to a certain extent.

LNM of esophageal cancer usually occurs in a certain order, and the earliest type of metastasis is localized LNM. The classical spreading process of tumor metastasis is from the primary focus to systemic metastasis, where normal cells of an organ or tissue proliferate beyond control due to genetic mutations and form a primary tumor. The migration of tumor cells through lymphatic vessels to the nearest regional lymph node represents a breakthrough of the tumor from the primary focus, but it remains confined to the local lymphatic drainage area (locoregional nodal metastasis). Tumor cells continue to spread along the lymphatic system to more distant lymph nodes or enter the circulation through lymphatic-vascular trafficking and “home” to distant lymph nodes. The next step in distant LNM is distant solid organ metastasis, in which tumor cells enter the circulation, evade immune clearance, and then colonize and form metastases in distant organs. This means that the tumor has spread throughout the body and is usually incurable. Treatment is aimed at prolonging survival and maintaining quality of life.

Upper esophageal cancer mainly metastasizes to neck lymph nodes (such as deep neck lymph nodes and supraclavicular lymph nodes), whereas middle esophageal cancer mainly metastasizes to mediastinal lymph nodes, including the anterior mediastinal lymph nodes, middle mediastinal lymph nodes, and posterior mediastinal lymph nodes. Lower esophageal cancer mainly metastasizes to abdominal lymph nodes, including the paragastric lymph nodes, para-abdominal aortic lymph nodes, and hilar lymph nodes. Distant lymph node metastases include supraclavicular, axillary, mediastinal, and abdominal lymph nodes. Lower esophageal cancer may further extend to the lymph nodes in other regions of the abdomen, especially the hilar and pancreatic lymph nodes, through the blood or lymphatic system. As cancer progresses, tumor cells may spread to other lymph nodes in the chest cavity, including the chest wall lymph nodes. Cancer cells spread through the lymphatic fluid to the lymphatic system of the gastrointestinal tract and may eventually spread to lymph nodes deeper in the abdominal cavity, such as the para-aortic lymph nodes of the abdomen.

The interpretable module employed in this study suggests that the outcome of solid organ metastases is somewhat predictive of the status of distant lymphatic metastases, as solid organ metastases are often the outcome of metastases. The lung is one of the most common sites of distant metastasis of esophageal cancer. Tumor cells can spread to the lungs through the bloodstream or lymphatic system, especially in the middle and lower parts of the esophagus. Lung metastasis usually occurs in the late stages of cancer, especially when the cancer cells have entered the lungs through the blood circulation. Tumor cells enter the liver through the bloodstream, leading to liver metastasis. The liver has a rich blood supply, which makes it a common site of cancer cell spread via the blood system. Liver metastasis often occurs in the middle to late stages of the disease, especially after the cancer has spread to the lungs, and the liver often becomes the next target for esophageal cancer metastasis. Bone, especially the spine, ribs, and pelvis, is a common site of metastasis in patients with advanced esophageal cancer. Bone metastasis usually occurs when the tumor has already spread throughout the body via blood circulation. As the tumor spreads further, bone metastasis gradually becomes increasingly obvious. Bone metastasis usually occurs after liver metastasis and may cause severe bone pain, fracture, and other symptoms. The brain is a less common metastatic site of esophageal cancer, and brain metastasis usually occurs when the tumor has spread widely and the treatment is insufficient. Although brain metastasis is a rarer metastatic site of esophageal cancer, it may still occur in patients with advanced disease. Brain metastasis usually occurs after lung, liver, and bone metastases, especially if the cancer cells reach the central nervous system through the blood. Patients with brain metastases may experience neurological-related symptoms such as headaches, seizures, and neurological dysfunction.

Regarding therapeutic strategies, there is no consensus on whether palliative radiotherapy or surgery is valuable for the treatment of metastatic esophageal cancer. Several retrospective and prospective studies have suggested that palliative radiotherapy can improve survival in patients with metastatic esophageal cancer (29-31). Several recent retrospective studies have revealed that resection of primary tumors may be considered for select groups of patients with stage IV esophageal cancer who achieve a favorable response to systemic chemotherapy (32). For advanced metastatic esophageal cancer, immunotherapy combined with chemotherapy is an effective approach. The Checkmate-648 clinical trial, which compared nivolumab in combination with chemotherapy or ipilimumab with chemotherapy for the first-line treatment of patients with ESCC, found that the combination regimens yielded significant improvement in OS and a durable response (33). Chemo-immunotherapy has become the first-line standard of care for patients with esophageal cancer, but the increase in chemotherapy-induced toxicity warrants attention, and a regimen consisting of de-escalated targeted immunotherapy may help reduce adverse effects.

Our study has several advantages. To begin, we screened clinical factors via machine learning to accurately predict the probability of distant LNM in patients with esophageal cancer. The prediction of distant LNM have not been extensively investigated. The prediction of distant LNM in esophageal cancer using machine learning models has not been extensively investigated. However, distant LNM plays an important role in prognosis and is a critical factor in determining subsequent treatment. To our knowledge, our study is the first to use machine learning to construct a model to predict distant LNM. This model is more reliable compared to traditional nomogram prediction models. Additionally, our work represents an extension of using artificial intelligence in the field of precision therapy, with the aim being to provide accurate diagnosis and individualized treatment for patients. Moreover, we effectively combined several staging factors and high-risk factors for predicting distant LNM. In fact, these metastases represent a certain degree of tumor progression, and the association of these metastatic factors with each other may indicate a poor prognosis. This finding suggests that future studies can improve personalized treatment by clarifying the relationships between clinical risk factors and thus enable predictions regarding key indicators. The presence of distant LNM is itself a sign of advanced tumor progression. Crucially, our analysis reveals that the high-risk factors for predicting LNM are often interrelated and co-occurring. This synergy between risk factors, rather than their isolated presence, provides a more powerful indicator of a poor prognosis. This finding suggests that future studies could improve personalized treatment by elucidating the complex relationships between clinical risk factors, thereby enabling more accurate predictions of patient outcomes.

However, our study involved several limitations that should also be acknowledged. First, we only included data from the SEER database for predictive modeling, meaning that the patients were exclusively from the United States and predominantly white. Populations from other countries were not considered, so it is necessary to explore the inclusion of other nations’ populations for modeling. Second, we used population data from our clinical center to validate the model, and thus, further validation in real-world populations from multiple centers is needed to ensure the accuracy of the model. Furthermore, multicenter prospective studies should be conducted to develop more robust algorithms, such as deep learning and ensemble models. Third, some treatment data on patients, such as data on targeted therapies and immunotherapies, were missing. Therefore, the factors included in predictive modeling might be insufficient, and elements relevant to risk factor assessment might have been missed.

Conclusions

We successfully developed and validated seven machine learning models for the prediction of distant metastasis in patients with esophageal cancer. Logistic regression was used to determine the correlation between clinical variables and distant LNM. The GB model can accurately predict metastasis and demonstrates good classification performance. The interpretable module applied in our study could explain how the variances correlated with tumor metastasis. The application of these models can assist clinicians in making more accurate treatment decisions and in providing personalized follow-up management, ultimately improving patient prognosis.

Acknowledgments

None.

Footnote

Reporting Checklist: The authors have completed the TRIPOD reporting checklist. Available at https://jtd.amegroups.com/article/view/10.21037/jtd-2025-484/rc

Peer Review File: Available at https://jtd.amegroups.com/article/view/10.21037/jtd-2025-484/prf

Funding: None.

Conflicts of Interest: Both authors have completed the ICMJE uniform disclosure form (available at https://jtd.amegroups.com/article/view/10.21037/jtd-2025-484/coif). The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Ethical Statement: The authors are accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved. The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and its subsequent amendments.

Open Access Statement: This is an Open Access article distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 4.0 International License (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0), which permits the non-commercial replication and distribution of the article with the strict proviso that no changes or edits are made and the original work is properly cited (including links to both the formal publication through the relevant DOI and the license). See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

References

- Bray F, Laversanne M, Sung H, et al. Global cancer statistics 2022: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J Clin 2024;74:229-63. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Rustgi AK, El-Serag HB. Esophageal carcinoma. N Engl J Med 2014;371:2499-509. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Matsuda S, Takeuchi M, Kawakubo H, et al. Lymph node metastatic patterns and the development of multidisciplinary treatment for esophageal cancer. Dis Esophagus 2023;36:doad006. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Lu H, Liu JF, Rong Y, et al. Survival benefits of adjuvant chemotherapy for patients with residual pathologic disease after neoadjuvant chemotherapy and surgery for locally advanced esophageal squamous cell carcinoma. J Gastrointest Surg 2024;28:867-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Greener JG, Kandathil SM, Moffat L, et al. A guide to machine learning for biologists. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 2022;23:40-55. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Schober P, Vetter TR. Logistic Regression in Medical Research. Anesth Analg 2021;132:365-6. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Hu J, Szymczak S. A review on longitudinal data analysis with random forest. Brief Bioinform 2023;24:bbad002. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Luna JM, Gennatas ED, Ungar LH, et al. Building more accurate decision trees with the additive tree. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2019;116:19887-93. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Li Y, Duan H, Wang S. An XGBoost predictive model of ongoing pregnancy in patients following hysteroscopic adhesiolysis. Reprod Biomed Online 2023;46:965-72. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Salditt M, Humberg S, Nestler S. Gradient Tree Boosting for Hierarchical Data. Multivariate Behav Res 2023;58:911-37. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Sugahara S, Ueno M. Exact Learning Augmented Naive Bayes Classifier. Entropy (Basel) 2021;23:1703. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Yuan G, Lv B, Hao C. Application of artificial neural networks in reproductive medicine. Hum Fertil (Camb) 2023;26:1195-201. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Hatwell J, Gaber MM, Atif Azad RM. Ada-WHIPS: explaining AdaBoost classification with applications in the health sciences. BMC Med Inform Decis Mak 2020;20:250. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Idarraga AJ, Luong G, Hsiao V, et al. False Negative Rates in Benign Thyroid Nodule Diagnosis: Machine Learning for Detecting Malignancy. J Surg Res 2021;268:562-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Chowdhury SU, Sayeed S, Rashid I, et al. Shapley-Additive-Explanations-Based Factor Analysis for Dengue Severity Prediction using Machine Learning. J Imaging 2022;8:229. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Okada G, Matsumoto Y, Habu D, et al. Relationship between GLIM criteria and disease-specific symptoms and its impact on 5-year survival of esophageal cancer patients. Clin Nutr 2021;40:5072-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Shang QX, Yang YS, Xu LY, et al. Prognostic Role of Nodal Skip Metastasis in Thoracic Esophageal Squamous Cell Carcinoma: A Large-Scale Multicenter Study. Ann Surg Oncol 2021;28:6341-52. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Wegen S, Claus K, Linde P, et al. Impact of FAPI-46/dual-tracer PET/CT imaging on radiotherapeutic management in esophageal cancer. Radiat Oncol 2024;19:44. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Chulroek T, Kordbacheh H, Wangcharoenrung D, et al. Comparative accuracy of qualitative and quantitative 18F-FDG PET/CT analysis in detection of lymph node metastasis from anal cancer. Abdom Radiol (NY) 2019;44:828-35. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Xu HY, Wu SX, Luo HS, et al. Analysis of definitive chemo-radiotherapy for esophageal cancer with supra-clavicular node metastasis based on CT in a single institutional retrospective study: a propensity score matching analysis. Radiat Oncol 2018;13:200. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Sun J, Huang L, Liu Y. Leveraging SEER data through machine learning to predict distant lymph node metastasis and prognosticate outcomes in hepatocellular carcinoma patients. J Gene Med 2024;26:e3732. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Wang J, Zhang X, Gan T, et al. Risk factors and a predictive nomogram for lymph node metastasis in superficial esophageal squamous cell carcinoma. World J Gastroenterol 2023;29:6138-47. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Chen H, Wu J, Guo W, et al. Clinical models to predict lymph nodes metastasis and distant metastasis in newly diagnosed early esophageal cancer patients: A population-based study. Cancer Med 2023;12:5275-92. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Huang J, Hu W, Pang L, et al. Value of Positive Lymph Node Ratio for Predicting Postoperative Distant Metastasis and Prognosis in Esophageal Squamous Cell Carcinoma. Oncol Res Treat 2015;38:424-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Yu YB. Risk factors for lymph node metastasis in superficial esophageal squamous cell carcinoma. World J Gastroenterol 2024;30:1810-4. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Zhu L, Zhao Z, Liu A, et al. Lymph node metastasis is not associated with survival in patients with clinical stage T4 esophageal squamous cell carcinoma undergoing definitive radiotherapy or chemoradiotherapy. Front Oncol 2022;12:774816. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Hamai Y, Emi M, Ibuki Y, et al. Distribution of Lymph Node Metastasis in Esophageal Squamous Cell Carcinoma After Trimodal Therapy. Ann Surg Oncol 2021;28:1798-807. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Wu SG, Zhang WW, He ZY, et al. Sites of metastasis and overall survival in esophageal cancer: a population-based study. Cancer Manag Res 2017;9:781-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Hingorani M, Dixit S, Johnson M, et al. Palliative Radiotherapy in the Presence of Well-Controlled Metastatic Disease after Initial Chemotherapy May Prolong Survival in Patients with Metastatic Esophageal and Gastric Cancer. Cancer Res Treat 2015;47:706-17. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Li T, Lv J, Li F, et al. Prospective randomized phase II study of concurrent chemoradiotherapy versus chemotherapy alone in stage IV esophageal squamous cell carcinoma. J Clin Oncol 2016;34:4050.

- Guttmann DM, Mitra N, Bekelman J, et al. Improved Overall Survival with Aggressive Primary Tumor Radiotherapy for Patients with Metastatic Esophageal Cancer. J Thorac Oncol 2017;12:1131-42. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Wang J, Suri JS, Allen PK, et al. Factors Predictive of Improved Outcomes With Multimodality Local Therapy After Palliative Chemotherapy for Stage IV Esophageal Cancer. Am J Clin Oncol 2016;39:228-35. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Doki Y, Ajani JA, Kato K, et al. Nivolumab Combination Therapy in Advanced Esophageal Squamous-Cell Carcinoma. N Engl J Med 2022;386:449-62. [Crossref] [PubMed]

(English Language Editor: J. Gray)