The big quantum buzzword these days is “quantum supremacy.” (It’s a term I despise, even as I acknowledge that the concept has some utility. I will explain in a moment). Unfortunately, this means that some researchers have focused on quantum supremacy as an end in itself, building useless devices to get there.

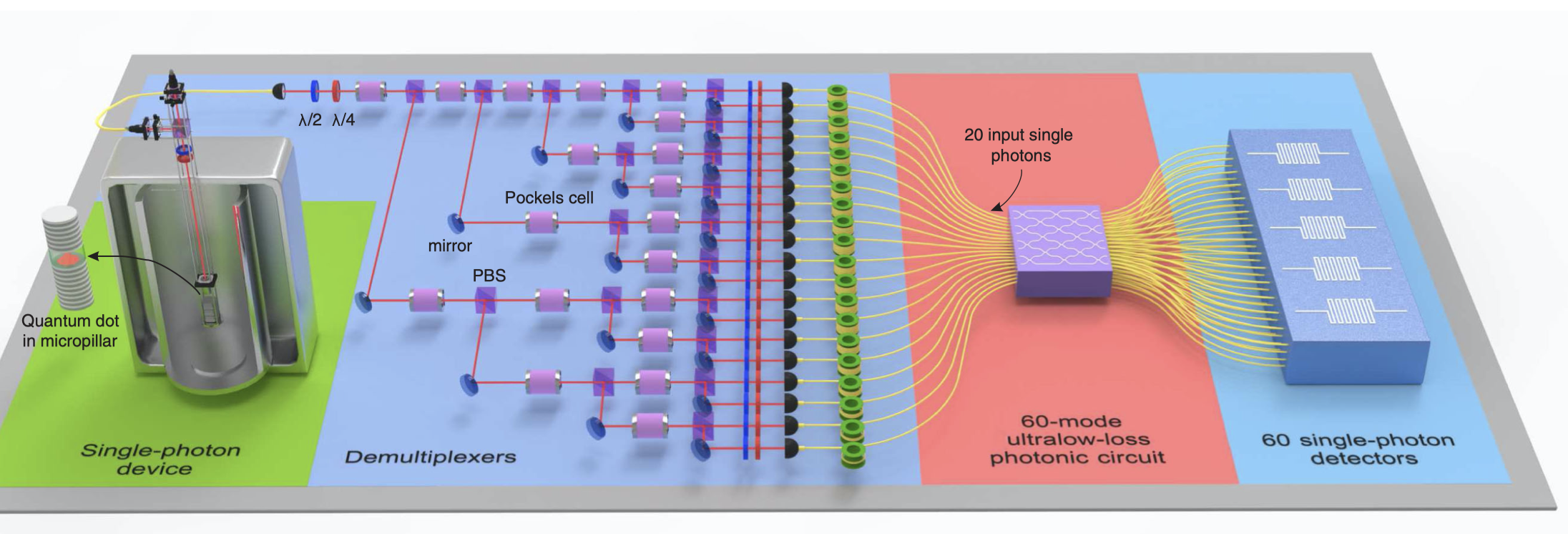

Now, optical quantum computers have joined the club with a painstakingly configured device that doesn’t quite manage to demonstrate quantum supremacy. But before we get to the news, let’s delve into the world of quantum supremacy.

The quest for quantum supremacy

“Quantum supremacy” boils down to a failure of mathematics, combined with a fear that the well will run dry before we’ve drunk our fill.

In a perfect world, a quantum computer operates perfectly. In this perfect world, you can generate a mathematical proof that shows a quantum computer will always outperform a classical computer on certain tasks, no matter how fast the classical computer is. Our world, however, is slightly less than perfect, and our quantum computers are not ideal, so these mathematical proofs might not apply.

As a result, to show performance advantages for quantum computers, we have to build an actual quantum computer that does something a classical computer can’t. Unfortunately, reliable quantum computers were, until recently, limited to just a few quantum bits (qubits). Because of this bit scarcity, any problem solvable on a quantum computer could be solved much faster on a classical computer, simply because the problems were so small.

One solution, of course, is to make quantum computers with a larger number of qubits so that they can handle larger problems. Once that is achieved, quantum computers should be faster than classical computers—provided those tricky mathematical proofs hold for non-ideal quantum computers.

Loading comments...

Loading comments...