The USS Zumwalt, the latest destroyer now undergoing acceptance trials, comes with a new type of naval artillery: the Advanced Gun System (AGS). The automated AGS can fire 10 rocket-assisted, precision-guided projectiles per minute at targets over 100 miles away.

Those projectiles use GPS and inertial guidance to improve the gun’s accuracy to a 50 meter (164 feet) circle of probable error—meaning that half of its GPS-guided shells will fall within that distance from the target. But take away the fancy GPS shells, and the AGS and its digital fire control system are no more accurate than mechanical analog technology that is nearly a century old.

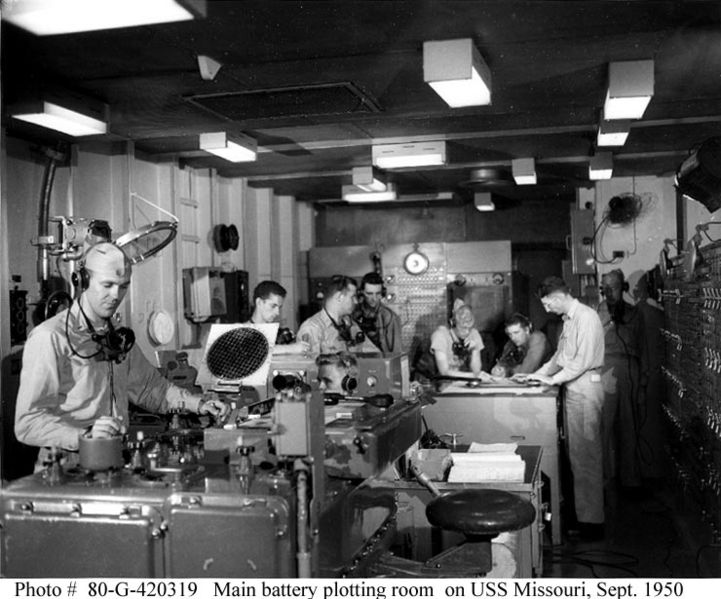

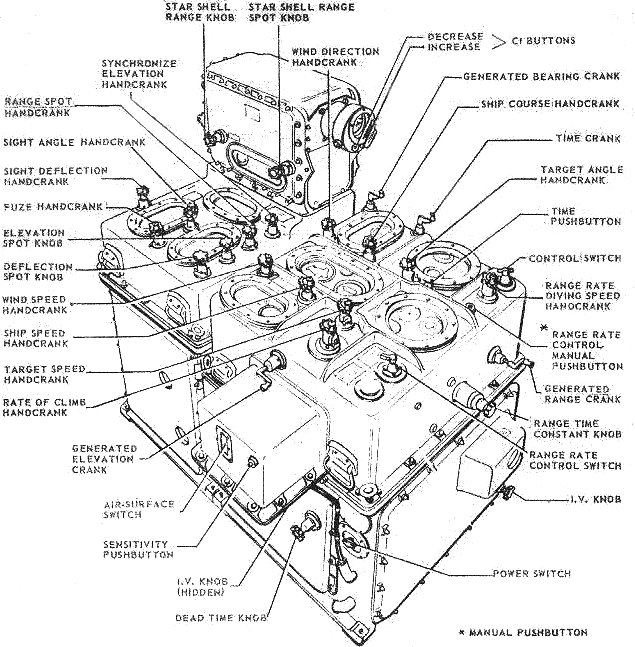

We're talking about electro-mechanical analog fire control computers like the Ford Instruments Mark 1A Fire Control Computer and Mark 8 Rangekeeper. These machines solved 20-plus variable calculus problems in real-time, constantly, long before digital computers got their sea legs. They were still in use when I served aboard the USS Iowa in the late 1980s.

There were a few efforts to marry these older systems to or replace them with digital technology during my tour, one of which (called the Advanced Gun Weapon System Technology Program) was remarkably like the AGS’s 100-mile shell: a GPS and inertially guided 11-inch dart-shaped shell wrapped in a 16-inch peel-away jacket, or sabot, that would have been able to fly nearly as far without the rocket assist thanks to the battleship’s big guns.

So why did the Navy never follow through with digitizing the battleship’s big guns? I asked retired Navy Captain David Boslaugh, former director of the Navy Tactical Embedded Computer Program Office, that question. And if anyone would know, it's Boslaugh. He played a role in the development of the Navy Tactical Data System—the forerunner to today’s Aegis systems, the mother of all digital sensor and fire control systems.

Loading comments...

Loading comments...