Universe of Obligation

Duration

One 50-min class periodSubject

- History

- Social Studies

Grade

6–8Language

English — USPublished

Access all resources for free now.

Your free Facing History account gives you access to all of this Lesson’s content and materials in Google Drive.

Get everything you need including content from this page.

About This Lesson

In this lesson, students build on their previous discussion about stereotypes by examining why humans form groups and what it means to belong. This examination begins the second stage of the Facing History scope and sequence, “We and They.” Students will learn a new concept, universe of obligation—the term sociologist Helen Fein coined to describe the circle of other individuals and groups within a society “toward whom obligations are owed, to whom rules apply, and whose injuries call for amends.” 1

Understanding the concept of universe of obligation provides important insights into the behavior of individuals, groups, and nations throughout history. It also helps students think more deeply about the benefits of being part of a society’s “in” group and the consequences of being part of an “out” group.

The activities in this lesson ask students to think about the people for whom they feel responsible. The activities also help students analyze the ways that their society designates who is worthy of respect and caring and who is not.

Essential Questions

Unit Essential Question: What does learning about the choices people made during the Weimar Republic, the rise of the Nazi Party, and the Holocaust teach us about the power and impact of our choices today?

Guiding Questions

What factors influence the extent to which we feel an obligation to help others? How does the way we view others influence our feelings of responsibility toward them?

Learning Objectives

- Students will apply a new concept of human behavior—universe of obligation—to analyze how individuals and societies determine who is deserving of respect and whose rights are worthy of protection.

- Students will recognize that a society’s universe of obligation often changes, expanding or shrinking depending on circumstances such as peace and prosperity or war and economic depression.

- 1Helen Fein, Accounting for Genocide (New York: Free Press, 1979), 4.

Materials

Teaching Notes

Before teaching this text set, please review the following information to help guide your preparation process.

Lesson Plan

Activity 1: Journal Responses: Groups and Belonging

Ask students to respond in their journals to the following prompt:

Think about a group you belong to. It might be your family, a team, a faith community, a club, a classroom, an online community, or some other type of group. How did you become a member of that group? Did you choose to be a member, or are you one automatically? What do you gain by belonging to that group? What, if anything, do you have to give up or hide about yourself to be a member?

Briefly debrief the prompt by asking students to share some of the things they gain by belonging to groups and some of the things they give up in order to belong. Honor student privacy and refrain from requiring all students to share their responses in detail.

Then pose a new question to students:

- Why do humans so often divide themselves into groups? When is this a good thing? When is it harmful?

Give students a few minutes to respond in their journals, and then discuss the question using the Think, Pair, Share strategy.

Activity 2: Introduce the Concept of “Universe of Obligation”

Introduce the concept of universe of obligation to students, and explain that it is one way to consider the benefits of belonging to groups and the consequences of being excluded. An individual’s or group’s universe of obligation represents the extent to which they feel responsible for others. We often feel a greater sense of responsibility for those who belong to the same groups that we do.

Pass out the reading Universe of Obligation and read it aloud.

This reading includes quotations that feature the perspectives of three people: David Hume, Chuck Collins, and William Graham Sumner (connection question 4). Re-read the quotations from each of these people to the class, and then discuss with students the following questions:

- In what ways do these three people agree? In what ways do they disagree?

- Which of these people seems to have the most inclusive universe of obligation? Which seems to have the most exclusive?

- Is it possible for everyone in the world to be included in person’s or country’s universe of obligation? If not, how should we prioritize?

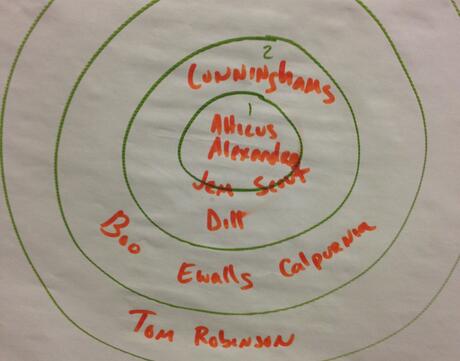

Activity 3: Illustrate Individual Universes of Obligation

Finally, ask students to illustrate their own universes of obligation using the graphic organizer on the Universe of Obligation handout. The concentric circles on this handout can help students visualize and diagram what an individual, group, or country’s universe of obligation might look like.

Give students time to follow the instructions and complete the activity on the handout. It might be helpful first to quickly brainstorm a variety of types of individuals and groups that might appear on one’s graphic organizer, including family, friends, neighbors, classmates, strangers in one’s town, and others.

Have students meet in groups of two or three to discuss their experience of trying to illustrate their universes of obligation. In their discussions, students should address some of the following questions:

- What was the experience of diagramming your universe of obligation like?

- What did you think about when deciding where to place certain groups in your universe of obligation? Which decisions were difficult? Which were easy?

- Under what conditions might your universe of obligation shift? What might cause you to move some groups to the center and others to the outside?

- What is the difference between an individual’s universe of obligation and that of a school, community, or country?

Assessment

Extension Activities

Get this lesson in Google Drive!

Log in to your Facing History account to access all lesson content & materials. If you don't have an account, Sign up today (it's fast, easy, and free!).

A Free Account allows you to:

- Access and save all content, such as lesson plans and activities, within Google Drive.

- Create custom, personalized collections to share with teachers and students.

- Instant access to over 200+ on-demand and in-person professional development events and workshops