My first computer was an Atari 600XL, a 16KB model with a cartridge slot and no disk drive which my parents suffered through a high-pressure time share sales pitch to obtain for me. And I loved it, not so much for playing the cartridge version of Star Raiders (though I did that, too) but because the machine opened the door to BASIC code and to writing one’s own programs. It was like a LEGO kit for the mind: if you could think it—and squeeze it into 16KB—you could build it.

But how to save these masterpieces? I quickly acquired a finicky, used tape drive to store my programs on standard cassette tapes, picked up some books from the library, and I was off, coding versions of “Hunt the Wumpus” and other early Unix delights that had been ported to BASIC for the new breed of home computer user. Then, as I was browsing the magazine rack at our public library one day in the mid-1980s, I came across a wondrous magazine called COMPUTE!. It contained cutting-edge programs—including plenty of games—with decent graphics. And the code was all free. I quickly grabbed every back issue the library would let me take and headed home.

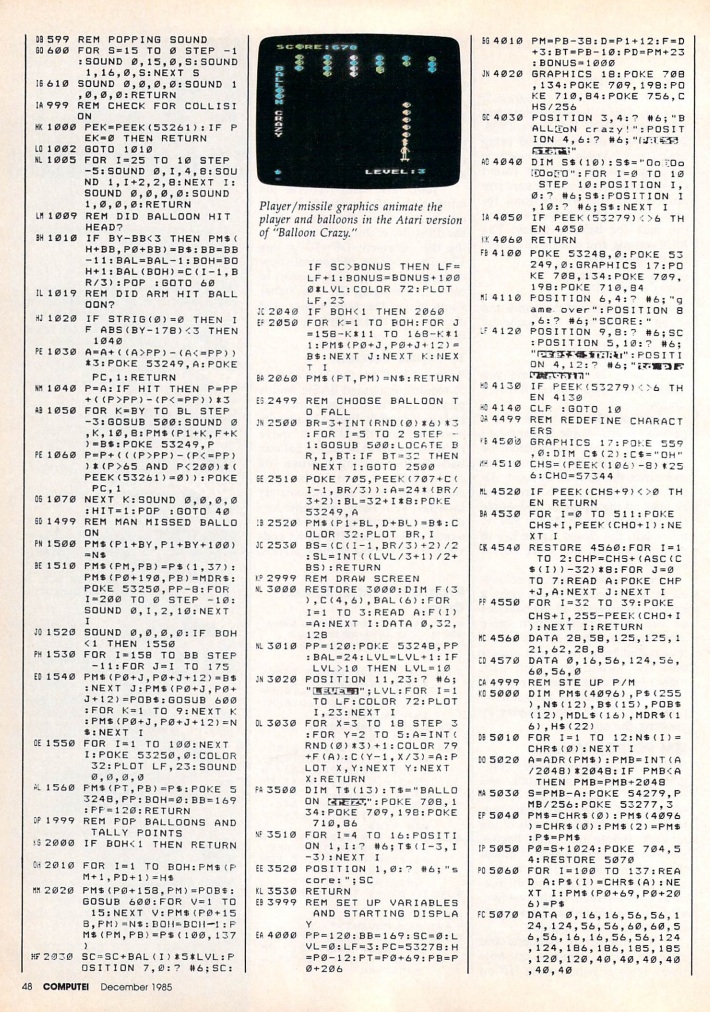

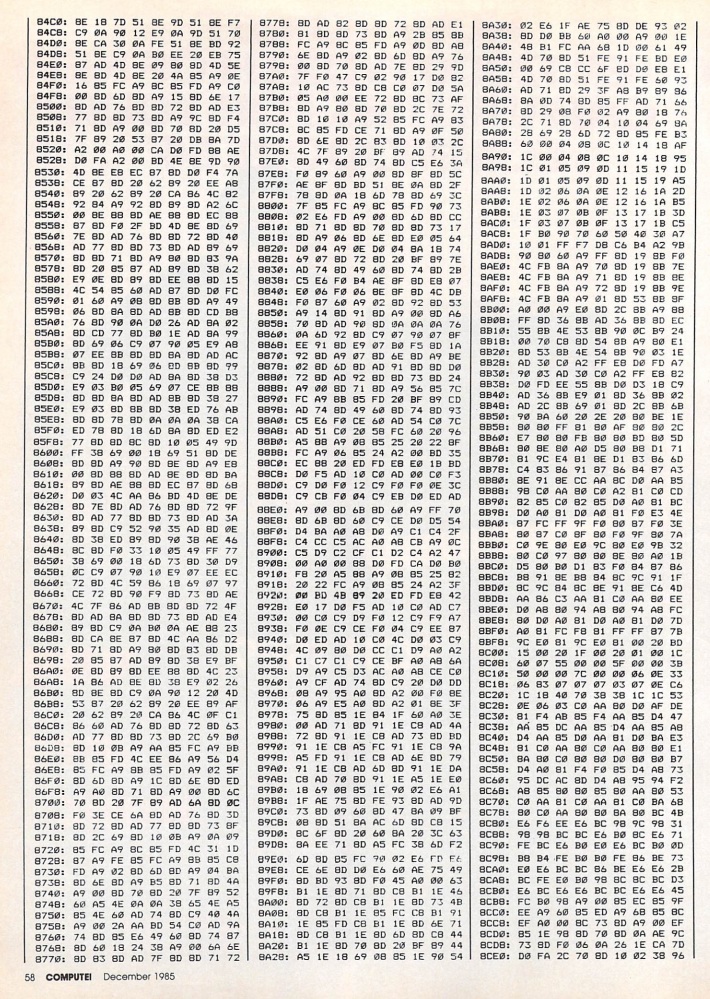

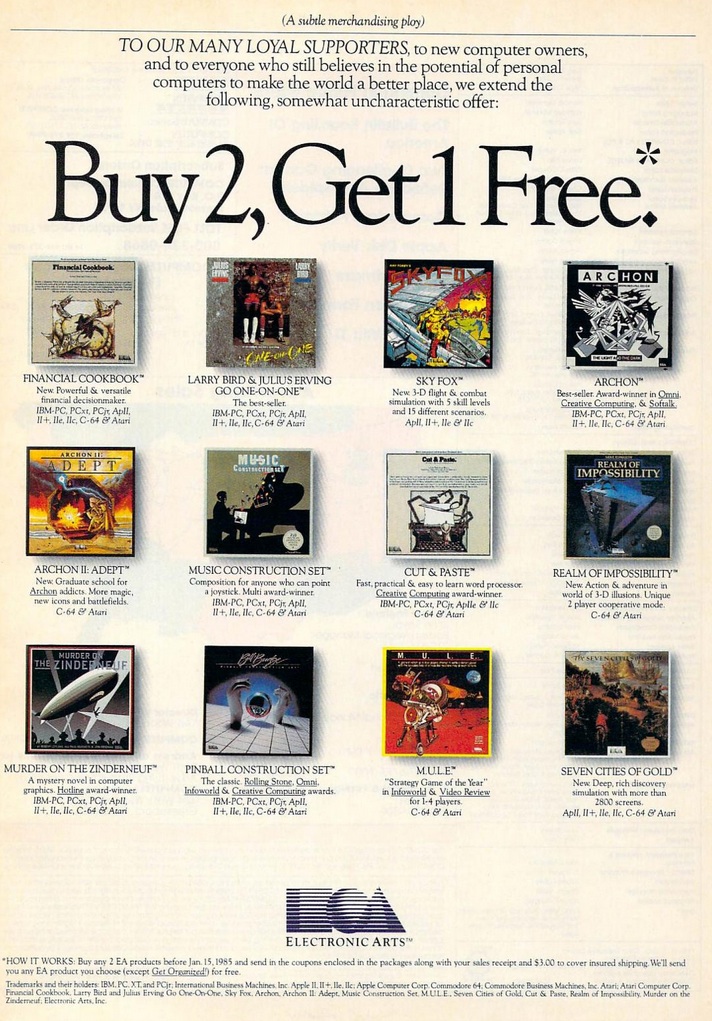

COMPUTE! made you work for those free programs, though. If you wanted to play a rudimentary strategy game like Beehive or experience the “haunting” 8-bit graphics of Witching Hour—and I did, badly—you had to type the programs in by hand. (Disks were available for some versions of these programs, but these cost money and required mailing away for subscriptions and using checks; I wasn’t about to do any of this at the time.) Whole sections of the magazine were dedicated to code for these programs, a situation made exponentially worse for the magazine’s editors by the fact that they had to write for so many platforms, including the Commodore 64, Apple II line, Atari, IBM PC, TI 99/4A, and more.

Loading comments...

Loading comments...