States of a Process in Operating Systems

Last Updated :

02 Dec, 2025

A process in an operating system passes through multiple states as it begins execution, waits for resources, gets scheduled, runs, and eventually finishes. When a program is launched and becomes a process, it transitions through several well-defined stages based on its activity and resource availability. These stages collectively describe the complete lifecycle of a process.

Common types of process state models include:

- Two-State Model

- Five-State Model

- Seven-State Model

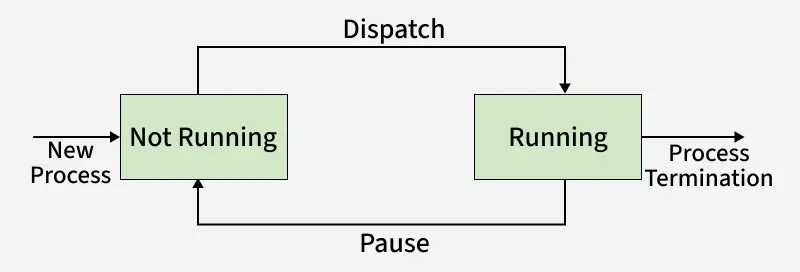

Two-State Model

The Two-State Model is the simplest representation of how a process behaves during its lifetime. It divides the process lifecycle into only two possible conditions. A process is either actively using the CPU to execute instructions or waiting until it gets a chance to run. This model helps illustrate the basic interaction between a process and the CPU.

The two states are

- Running: The process is currently using the CPU to execute its tasks.

- Not Running: The process is not using the CPU. It may be waiting for input, waiting for resources, or simply paused.

When a new process is created, it starts in the not running state. Initially, this process is kept in a program called the dispatcher. here’s what happens step by step:

- Not Running State: A newly created process starts here since it is not yet using the CPU.

- Dispatcher Role: The dispatcher checks if the CPU is free for a new process.

- Moving to Running State: If the CPU is available, the dispatcher loads the process onto it, shifting it to the running state.

- CPU Scheduler Role: The scheduler selects which process should run next based on the OS’s scheduling policy.

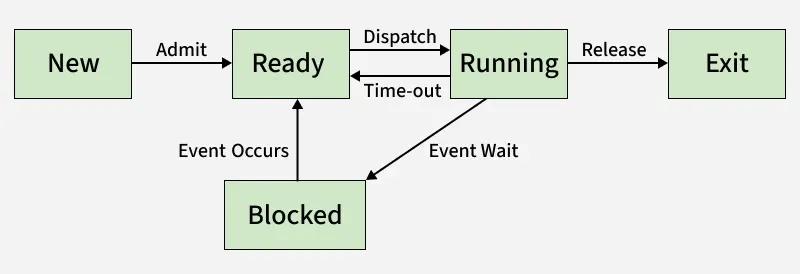

The Five-State Model

The five-state process lifecycle expands the basic two-state idea by separating processes that are simply waiting for CPU time from those that cannot run because they are waiting for an external event. This makes the model more accurate for real operating systems, where processes may pause for input, data, or device responses before continuing.

Five-State Model

Five-State ModelThe five states are:

- New: The process has just been created. It hasn’t started running yet, but its PCB (Process Control Block) is prepared.

- Ready: The process is loaded into memory and prepared to run as soon as the CPU becomes free.

- Running: The CPU is currently executing this process. With a single CPU system, only one process can be in this state at a time.

- Blocked/Waiting: The process cannot continue execution because it is waiting for an event like I/O completion or data input.

- Exit/Terminate: The process has completed its execution or has been stopped, and the operating system removes it from memory.

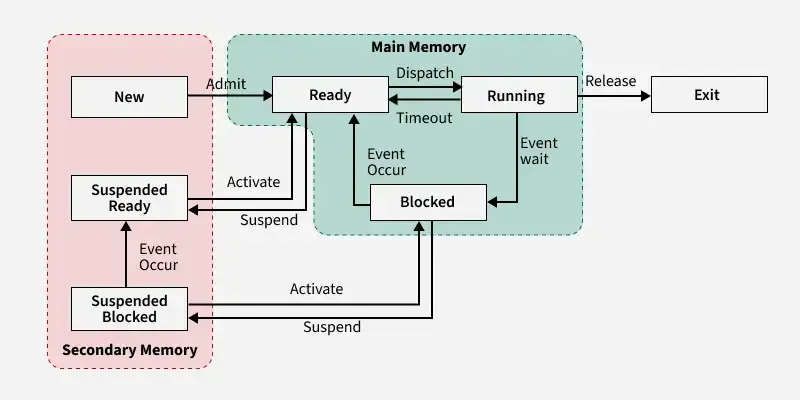

The Seven-State Model

A process moves through different states as it is created, prepared for execution, runs on the CPU, waits for resources, or completes. These states help the operating system manage how processes use memory, CPU, and I/O devices.

Seven State

Seven StateThe main process states are:

- New: The process is in the creation phase. The program exists in secondary memory, and the OS prepares its PCB before loading it into main memory.

- Ready: The process has been loaded into main memory and is prepared to run. It is waiting in the ready queue until the CPU becomes available.

- Running: The CPU is currently executing the instructions of the process. Only one process can be in this state at a time on a single-processor system.

- Blocked/Waiting: The process cannot continue because it is waiting for an event such as I/O completion, user input, or access to a locked resource. Once the event is complete, it moves back to the ready state.

- Terminated: The process has completed its execution or has been stopped. The OS deletes its PCB and frees all resources allocated to it.

- Suspend Ready: A ready process that has been swapped out of main memory and placed in secondary storage due to memory shortage. When brought back to main memory, it returns to the ready state.

- CPU-Bound / I/O-Bound: A CPU-bound process spends most of its time performing computations, while an I/O-bound process spends more time waiting for input/output operations.

Movement of a Process From One State to Another

A process transitions between different states depending on its progress and the availability of system resources. These movements help the operating system manage tasks efficiently.

- New → Ready:

A process is created, resources are allocated, and it is loaded into main memory. - Ready → Running:

The scheduler selects a ready process and assigns the CPU to it. - Running → Blocked (Waiting):

The process must wait for an event or resource (e.g., I/O, user input, system call). - Blocked → Ready:

The event completes or the needed resource becomes available, so the process is ready to run again. - Running → Ready:

The OS preempts the running process—often because a higher-priority process becomes ready. - Running → Terminated:

The process completes its execution or is forcefully stopped. - Blocked → Terminated:

The process waiting for an event is aborted or killed by the OS or another process. - (General Rule):

A process may move between ready, running, and blocked many times, but new and terminated happen only once in its lifetime.

Types of Schedulers

- Long-Term Scheduler:

The long-term scheduler decides which new processes should enter the ready state and controls the degree of multiprogramming. - Short-Term Scheduler:

The Short-term scheduler selects the next process from the ready queue to run on the CPU and works very frequently. - Medium-Term Scheduler:

The medium-term scheduler handles swapping by suspending processes and moving them between main memory and secondary storage.

Multiprogramming

We have many processes ready to run. There are two types of multiprogramming:

- Preemption: Process is forcefully removed from CPU. Pre-emption is also called time sharing or multitasking.

- Non-Preemption: Processes are not removed until they complete the execution. Once control is given to the CPU for a process execution, till the CPU releases the control by itself, control cannot be taken back forcibly from the CPU.

The number of processes that can reside in the ready state at maximum decides the degree of multiprogramming, e.g., if the degree of programming = 100, this means 100 processes can reside in the ready state at maximum.

Operation on The Process

- Creation: A process is created and placed in the ready queue (main memory), where it waits to be executed.

- Scheduling: The operating system selects one process from the ready queue to run next. This selection step is called scheduling.

- Execution: The CPU starts running the chosen process. If the process needs to wait for an event or resource, it becomes blocked, and the CPU switches to another process.

- Termination: Once the process completes its task, the OS terminates it and clears its context.

- Blocking: When a process waits for an event or resource (like I/O), it enters the blocked state and cannot continue until that event is completed.

- Context Switching: When the OS switches from one process to another, it saves the current process’s context and loads the next one. This switching is called context switching.

- Inter-Process Communication (IPC): Processes often need to exchange data or coordinate. The OS supports IPC using mechanisms like shared memory, message passing, and synchronization tools.

These states—new, ready, running, waiting, and terminated—represent different stages in a process's life cycle. By transitioning through these states, the operating system ensures that processes are executed smoothly, resources are allocated effectively, and the overall performance of the computer is optimized.

Explore

OS Basics

Process Management

Memory Management

I/O Management

Important Links

My Profile