Abstract

Purpose

This study aims to estimate the health and economic burden of osteoporosis in Singapore from 2017 to 2035, and to quantify the impact of increasing the treatment rate of osteoporosis.

Methods

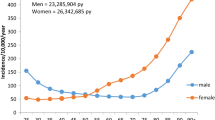

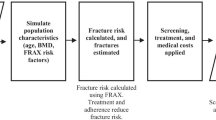

Population forecast data of women and men aged 50 and above in Singapore from 2017 to 2035 was used along with prevalence rates of osteoporosis to project the osteoporosis population over time. The population projections by sex and age group were used along with osteoporotic fracture incidence rates by fracture type (hip, vertebral, other), and average direct and indirect costs per case to forecast the number of fractures, the total direct health care costs, and the total indirect costs due to fractures in Singapore. Data on treatment rates and effects were used to model the health and economic impact of increasing treatment rate of osteoporosis, using different hypothetical levels.

Results

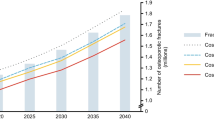

Between 2017 and 2035, the incidence of osteoporotic fractures is projected to increase from 15,267 to 24,104 (a 57.9% increase) F 10,717 to 17,225 (a 60.7% increase) and M 4550 to 6878 (a 51.2% increase). The total economic burden (including direct costs and indirect costs to society) associated with these fractures is estimated at S$183.5 million in 2017 and is forecasted to grow to S$289.6 million by 2035. However, increasing the treatment rate for osteoporosis could avert up to 29,096 fractures over the forecast period (2017–2035), generating cumulative total cost savings of up to S$330.6 million.

Conclusion

Efforts to improve the detection, diagnosis, and treatment of osteoporosis are necessary to reduce the growing clinical, economic, and societal burden of fractures in Singapore.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

International Osteoporosis Foundation (2013) Asia-Pacific Audit: Singapore

Svedbom A, Hernlund E, Ivergard M, Compston J, Cooper C, Stenmark J, McCloskey EV, Jonsson B, Kanis JA, IOF EURPo (2013) Osteoporosis in the European Union: a compendium of country-specific reports. Arch Osteoporos 8:137. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11657-013-0137-0

Yung CK, Fook-Chong S, Chandran M (2012) The prevalence of recognized contributors to secondary osteoporosis in South East Asian men and post-menopausal women. Are Z score diagnostic thresholds useful predictors of their presence? Arch Osteoporos 7:49–56. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11657-012-0078-z

Cheung C-L, Ang SB, Chadha M, Chow ES-L, Chung Y-S, Hew FL, Jaisamrarn U, Ng H, Takeuchi Y, Wu C-H, Xia W, Yu J, Fujiwara S (2018) An updated hip fracture projection in Asia: the Asian Federation of Osteoporosis Societies study. Osteoporosis Sarcopenia 4(1):16–21. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.afos.2018.03.003

Cooper C, Campion G, Melton LJ 3rd (1992) Hip fractures in the elderly: a world-wide projection. Osteoporos Int 2(6):285–289

Gullberg B, Johnell O, Kanis JA (1997) World-wide projections for hip fracture. Osteoporos Int 7(5):407–413

Koh LK, Saw SM, Lee JJ, Leong KH, Lee J, National Working Committee on O (2001) Hip fracture incidence rates in Singapore 1991-1998. Osteoporos Int 12(4):311–318

International Osteoporosis Foundation (2009) The Asian audit epidemiology, costs and burden of osteoporosis in Asia 2009. Switzerland

Chau PH, Wong M, Lee A, Ling M, Woo J (2013) Trends in hip fracture incidence and mortality in Chinese population from Hong Kong 2001-09. Age Ageing 42(2):229–233. https://doi.org/10.1093/ageing/afs177

Chen FP, Shyu YC, Fu TS, Sun CC, Chao AS, Tsai TL, Huang TS (2017) Secular trends in incidence and recurrence rates of hip fracture: a nationwide population-based study. Osteoporos Int 28(3):811–818. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00198-016-3820-3

Yong EL, Ganesan G, Kramer MS, Logan S, Lau TC, Cauley JA, Tan KB (2019) Hip fractures in Singapore: ethnic differences and temporal trends in the new millennium. Osteoporos Int 30:879–886. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00198-019-04839-5

Tay E (2016) Hip fractures in the elderly: operative versus nonoperative management. Singapore Med J 57(4):178–181. https://doi.org/10.11622/smedj.2016071

Wong MK, Arjandas Ching LK, Lim SL, Lo NN (2002) Osteoporotic hip fractures in Singapore--costs and patient’s outcome. Ann Acad Med Singap 31(1):3–7

Mitra AK, Low CK, Chao AK, Tan SK (1994) Social aspects in patients following proximal femoral fractures. Ann Acad Med Singapore. Ann Acad Med Singapore 23(6):876–878

Lee AY, Chua BS, Howe TS (2007) One-year outcome of hip fracture patients admitted to a Singapore hospital: quality of life post-treatment. Singap Med J 48(11):996–999

Kung AW, Fan T, Xu L, Xia WB, Park IH, Kim HS, Chan SP, Lee JK, Koh L, Soong YK, Soontrapa S, Songpatanasilp T, Turajane T, Yates M, Sen S (2013) Factors influencing diagnosis and treatment of osteoporosis after a fragility fracture among postmenopausal women in Asian countries: a retrospective study. BMC Womens Health 13:7. https://doi.org/10.1186/1472-6874-13-7

Gani L, Reddy SK, Alsuwaigh R, Khoo J, King TFJ (2017) High prevalence of missed opportunities for secondary fracture prevention in a regional general hospital setting in Singapore. Arch Osteoporos 12(1):60–64. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11657-017-0356-x

Department of Statistics S (2017) Popul Trends 2017. https://www.singstat.gov.sg/publications/population-trends. Accessed February 9 2018

Lee J, Lee S, Jang S, Ryu OH (2013) Age-related changes in the prevalence of osteoporosis according to gender and skeletal site: the Korea National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey 2008-2010. Endocrinol Metab (Seoul) 28(3):180–191. https://doi.org/10.3803/EnM.2013.28.3.180

Chandran M, Tan MZ, Cheen M, Tan SB, Leong M, Lau TC (2013) Secondary prevention of osteoporotic fractures--an “OPTIMAL” model of care from Singapore. Osteoporos Int 24(11):2809–2817. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00198-013-2368-8

Tan LT, Wong SJ, Kwek EB (2017) Inpatient cost for hip fracture patients managed with an orthogeriatric care model in Singapore. Singapore Med J 58(3):139–144. https://doi.org/10.11622/smedj.2016065

Ng CS, Lau TC, Ko Y (2017) Cost of osteoporotic fractures in Singapore. Value Health Reg Issues 12:27–35. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.vhri.2016.12.002

Watts JJ, Abimanyi-Ochom, J., Sanders, K.M. Osteoporosis costing all Australians - a new burden of disease analysis - 2012 to 2022

Marshall D, Johnell O, Wedel H (1996) Meta-analysis of how well measures of bone mineral density predict occurrence of osteoporotic fractures. BMJ 312(7041):1254–1259. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.312.7041.1254

Wells GA, Cranney A, Peterson J, Boucher M, Shea B, Robinson V, Coyle D, Tugwell P (2008) Alendronate for the primary and secondary prevention of osteoporotic fractures in postmenopausal women. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 1:CD001155. https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD001155.pub2

Schilcher J, Michaelsson K, Aspenberg P (2011) Bisphosphonate use and atypical fractures of the femoral shaft. N Engl J Med 364(18):1728–1737. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa1010650

Wysowski DK (2009) Reports of esophageal cancer with oral bisphosphonate use. N Engl J Med 360(1):89–90. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMc0808738

Black DM, Delmas PD, Eastell R, Reid IR, Boonen S, Cauley JA, Cosman F, Lakatos P, Leung PC, Man Z, Mautalen C, Mesenbrink P, Hu H, Caminis J, Tong K, Rosario-Jansen T, Krasnow J, Hue TF, Sellmeyer D, Eriksen EF, Cummings SR, Trial HPF (2007) Once-yearly zoledronic acid for treatment of postmenopausal osteoporosis. N Engl J Med 356(18):1809–1822. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa067312

Ruggiero SL, Mehrotra B, Rosenberg TJ, Engroff SL (2004) Osteonecrosis of the jaws associated with the use of bisphosphonates: a review of 63 cases. J Oral Maxillofac Surg 62(5):527–534

Jha S, Wang Z, Laucis N, Bhattacharyya T (2015) Trends in media reports, oral bisphosphonate prescriptions, and hip fractures 1996-2012: an ecological analysis. J Bone Miner Res 30(12):2179–2187. https://doi.org/10.1002/jbmr.2565

Wang Z, Bhattacharyya T (2011) Trends in incidence of subtrochanteric fragility fractures and bisphosphonate use among the US elderly, 1996-2007. J Bone Miner Res 26(3):553–560. https://doi.org/10.1002/jbmr.233

Wang Z, Ward MM, Chan L, Bhattacharyya T (2014) Adherence to oral bisphosphonates and the risk of subtrochanteric and femoral shaft fractures among female medicare beneficiaries. Osteoporos Int 25(8):2109–2116. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00198-014-2738-x

Whitaker M, Guo J, Kehoe T, Benson G (2012) Bisphosphonates for osteoporosis--where do we go from here? N Engl J Med 366(22):2048–2051. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMp1202619

International Osteoporosis Foundation (2005) The adherence gap: why osteoporosis patients don’t continue with treatment

Rabenda V, Hiligsmann M, Reginster JY (2009) Poor adherence to oral bisphosphonate treatment and its consequences: a review of the evidence. Expert Opin Pharmacother 10(14):2303–2315. https://doi.org/10.1517/14656560903140533

Freemantle N, Satram-Hoang S, Tang ET, Kaur P, Macarios D, Siddhanti S, Borenstein J, Kendler DL, Investigators D (2012) Final results of the DAPS (Denosumab Adherence Preference Satisfaction) study: a 24-month, randomized, crossover comparison with alendronate in postmenopausal women. Osteoporos Int 23(1):317–326. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00198-011-1780-1

Cummings SR, San Martin J, McClung MR, Siris ES, Eastell R, Reid IR, Delmas P, Zoog HB, Austin M, Wang A, Kutilek S, Adami S, Zanchetta J, Libanati C, Siddhanti S, Christiansen C, Trial F (2009) Denosumab for prevention of fractures in postmenopausal women with osteoporosis. N Engl J Med 361(8):756–765. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa0809493

Kanis JA, Oden A, Johnell O, Jonsson B, de Laet C, Dawson A (2001) The burden of osteoporotic fractures: a method for setting intervention thresholds. Osteoporos Int 12(5):417–427. https://doi.org/10.1007/s001980170112

Fujiwara S, Kasagi F, Masunari N, Naito K, Suzuki G, Fukunaga M (2003) Fracture prediction from bone mineral density in Japanese men and women. J Bone Miner Res 18(8):1547–1553. https://doi.org/10.1359/jbmr.2003.18.8.1547

Pongchaiyakul C, Nguyen ND, Jones G, Center JR, Eisman JA, Nguyen TV (2005) Asymptomatic vertebral deformity as a major risk factor for subsequent fractures and mortality: a long-term prospective study. J Bone Miner Res 20(8):1349–1355. https://doi.org/10.1359/JBMR.050317

Center JR, Nguyen TV, Schneider D, Sambrook PN, Eisman JA (1999) Mortality after all major types of osteoporotic fracture in men and women: an observational study. Lancet 353(9156):878–882. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0140-6736(98)09075-8

Keen RW (2003) Burden of osteoporosis and fractures. Curr Osteoporos Rep 1(2):66–70

Hiligsmann M, Reginster JY (2011) Cost effectiveness of denosumab compared with oral bisphosphonates in the treatment of post-menopausal osteoporotic women in Belgium. Pharmacoeconomics 29(10):895–911. https://doi.org/10.2165/11539980-000000000-00000

Hiligsmann M, Rabenda V, Gathon HJ, Ethgen O, Reginster JY (2010) Potential clinical and economic impact of nonadherence with osteoporosis medications. Calcif Tissue Int 86(3):202–210

Funding

This study was funded by Amgen Inc.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

Manju Chandran, Tang Ching Lau, Isabelle Gagnon-Arpin, Alexandru Dobrescu, and Wenshan Li have no conflict of interest. Mallory Leung, Narendra Patil, and Zhongyun Zhao hold Amgen stock and are employees of Amgen.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Appendices

Technical appendix

Example of how fracture rates were estimated for e.g. females aged 50–59 years

The base risks of fractures by gender and age group are calculated using the following formulae, given information on incidence rate, relative risk of fracture of osteoporotic patients vs. patients without osteoporosis, and the prevalence rate of osteoporosis.

i.e., the incidence rate of hip fracture for female patients is 253 cases per 100,000 persons. Given the population of females aged 50–59 is 456,978, the number of hip fracture cases for female aged 50–59 is 0.00253 × 456,978 = 1156.

Take an example of female patients in the age group of 50–59. The base risk of hip fracture is given by:

In the treatment scenario, since we assume the increase in treatment is fully attributed to the use of denosumab, the relative risk of FX for the OP patients is the weighted average between RROsteoporosis and RRDenosumab:

where ΔTR = 10%, 20%, 30%, or 47% uptake of denosumab.

RRDenosumab is the relative risk of fracture of OP patients with intake of Denosumab, i.e., RRDenosumab = RROsteoporosis × (1-relative risk reduction of denosumab by fracture type).

In the counterfactual exercise of ΔTR = 10% uptake of denosumab,

The RRnew are then plugged into the incidence rate equation to imply the new incidence rate of fractures in order to predict the incidence of fracture by various scenarios.

The new incidence of hip fracture with a 10% uptake of denosumab is:

Given 10% uptake of denosumab, the incidence rate for female hip fracture patients, 50–59 years of age, is 250 cases per 100,000 persons. With the assumption of 10% uptake of denosumab, the number of cases in 2017 is 0.002504 × 456,978 = 1144.

Therefore, the number of hip fracture cases averted for female aged 50–59 is 1156–1144 = 12.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Chandran, M., Lau, T.C., Gagnon-Arpin, I. et al. The health and economic burden of osteoporotic fractures in Singapore and the potential impact of increasing treatment rates through more pharmacological options. Arch Osteoporos 14, 114 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11657-019-0664-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11657-019-0664-4