Abstract

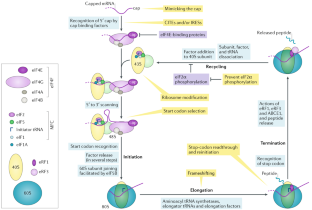

Viruses must co-opt the cellular translation machinery to produce progeny virions. Eukaryotic viruses have evolved a variety of ways to manipulate the cellular translation apparatus, in many cases using elegant RNA-centred strategies. Viral RNAs can alter or control every phase of protein synthesis and have diverse targets, mechanisms and structures. In addition, as cells attempt to limit infection by downregulating translation, some of these viral RNAs enable the virus to overcome this response or even take advantage of it to promote viral translation over cellular translation. In this Review, we present important examples of viral RNA-based strategies to exploit the cellular translation machinery. We describe what is understood of the structures and mechanisms of diverse viral RNA elements that alter or regulate translation, the advantages that are conferred to the virus and some of the major unknowns that provide motivation for further exploration.

This is a preview of subscription content, access via your institution

Access options

Access Nature and 54 other Nature Portfolio journals

Get Nature+, our best-value online-access subscription

$32.99 / 30 days

cancel any time

Subscribe to this journal

Receive 12 print issues and online access

$259.00 per year

only $21.58 per issue

Buy this article

- Purchase on SpringerLink

- Instant access to the full article PDF.

USD 39.95

Prices may be subject to local taxes which are calculated during checkout

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Hinnebusch, A. G. & Lorsch, J. R. The mechanism of eukaryotic translation initiation: new insights and challenges. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Biol. 4, a011544 (2012).

Dever, T. E. & Green, R. The elongation, termination, and recycling phases of translation in eukaryotes. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Biol. 4, a013706 (2012).

Nurenberg, E. & Tampe, R. Tying up loose ends: ribosome recycling in eukaryotes and archaea. Trends Biochem. Sci. 38, 64–74 (2013).

Spriggs, K. A., Bushell, M. & Willis, A. E. Translational regulation of gene expression during conditions of cell stress. Mol. Cell 40, 228–237 (2010).

Walsh, D., Mathews, M. B. & Mohr, I. Tinkering with translation: protein synthesis in virus-infected cells. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Biol. 5, a012351 (2013).

Walsh, D. & Mohr, I. Viral subversion of the host protein synthesis machinery. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 9, 860–875 (2011).

Jan, E., Mohr, I. & Walsh, D. A. Cap-to-tail guide to mRNA translation strategies in virus-infected cells. Annu. Rev. Virol. 3, 283–307 (2016).

Ramanathan, A., Robb, G. B. & Chan, S. H. mRNA capping: biological functions and applications. Nucleic Acids Res. 44, 7511–7526 (2016).

Decroly, E., Ferron, F., Lescar, J. & Canard, B. Conventional and unconventional mechanisms for capping viral mRNA. Nat. Rev. Microb. 10, 51–65 (2011).

Bouloy, M., Plotch, S. J. & Krug, R. M. Globin mRNAs are primers for the transcription of influenza viral RNA in vitro. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 75, 4886–4890 (1978). This study reports that the capped ends of endogenous mRNAs are ‘hijacked’ to allow influenza virus transcription and translation.

Fujimura, T. & Esteban, R. Cap snatching in yeast L-BC double-stranded RNA totivirus. J. Biol. Chem. 288, 23716–23724 (2013).

Fujimura, T. & Esteban, R. Cap-snatching mechanism in yeast L-A double-stranded RNA virus. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 108, 17667–17671 (2011).

Dong, H. et al. Flavivirus RNA methylation. J. Gen. Virol. 95, 763–778 (2014).

Hyde, J. L. & Diamond, M. S. Innate immune restriction and antagonism of viral RNA lacking 2′-O methylation. Virology 479–480, 66–74 (2015).

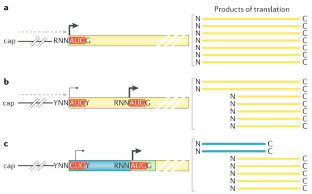

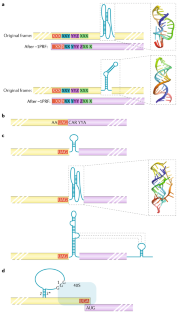

Kozak, M. Point mutations define a sequence flanking the AUG initiator codon that modulates translation by eukaryotic ribosomes. Cell 44, 283–292 (1986). This study provides important insight into the details of translation start codon selection, showing that translation initiation is not as simple as finding the first AUG codon.

Vera-Otarola, J. et al. The Andes hantavirus NSs protein is expressed from the viral small mRNA by a leaky scanning mechanism. J. Virol. 86, 2176–2187 (2011).

Andreev, D. E. et al. Insights into the mechanisms of eukaryotic translation gained with ribosome profiling. Nucleic Acids Res. 45, 513–526 (2017). This article presents a review on the power of ribosome profiling to provide insight into various translation mechanisms.

Turina, M., Desvoyes, B. & Scholthof, K. B. A gene cluster encoded by panicum mosaic virus is associated with virus movement. Virology 266, 120–128 (1999).

Haimov, O., Sinvani, H. & Dikstein, R. Cap-dependent, scanning-free translation initiation mechanisms. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1849, 1313–1318 (2015).

Ventoso, I. Adaptive changes in alphavirus mRNA translation allowed colonization of vertebrate hosts. J. Virol. 86, 9484–9494 (2012).

Ventoso, I. et al. Translational resistance of late alphavirus mRNA to eIF2alpha phosphorylation: a strategy to overcome the antiviral effect of protein kinase PKR. Genes Dev. 20, 87–100 (2006).

Sanz, M. A., Gonzalez Almela, E. & Carrasco, L. Translation of sindbis subgenomic mRNA is independent of eIF2, eIF2A and eIF2D. Sci. Rep. 7, 43876 (2017).

Toribio, R., Diaz-Lopez, I., Boskovic, J. & Ventoso, I. An RNA trapping mechanism in Alphavirus mRNA promotes ribosome stalling and translation initiation. Nucleic Acids Res. 44, 4368–4380 (2016).

Jha, S. et al. Trans-kingdom mimicry underlies ribosome customization by a poxvirus kinase. Nature 546, 651–655 (2017).

Vachon, V. K. & Conn, G. L. Adenovirus VA RNA: an essential pro-viral non-coding RNA. Virus Res. 212, 39–52 (2016).

Iwakiri, D. Multifunctional non-coding Epstein-Barr virus encoded RNAs (EBERs) contribute to viral pathogenesis. Virus Res. 212, 30–38 (2016).

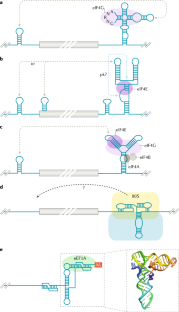

Mailliot, J. & Martin, F. Viral internal ribosomal entry sites: four classes for one goal. Wiley Interdiscip. Rev. RNA 9, e1458 (2018).

Asnani, M., Kumar, P. & Hellen, C. U. Widespread distribution and structural diversity of Type IV IRESs in members of Picornaviridae. Virology 478, 61–74 (2015). This study describes the diversity of a type of IRES and illustrates how useful and adaptable this type of RNA element and mechanism must be.

Filbin, M. E. & Kieft, J. S. Toward a structural understanding of IRES RNA function. Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol. 19, 267–276 (2009).

Kerr, C. H. & Jan, E. Commandeering the ribosome: lessons learned from dicistroviruses about translation. J. Virol. 90, 5538–5540 (2016).

Hertz, M. I. & Thompson, S. R. Mechanism of translation initiation by Dicistroviridae IGR IRESs. Virology 411, 355–361 (2011).

Colussi, T. M. et al. Initiation of translation in bacteria by a structured eukaryotic IRES RNA. Nature 519, 110–113 (2015).

Pfingsten, J. S., Costantino, D. A. & Kieft, J. S. Structural basis for ribosome recruitment and manipulation by a viral IRES RNA. Science 314, 1450–1454 (2006).

Schuler, M. et al. Structure of the ribosome-bound cricket paralysis virus IRES RNA. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 13, 1092–1096 (2006).

Spahn, C. M. et al. Cryo-EM visualization of a viral internal ribosome entry site bound to human ribosomes: the IRES functions as an RNA-based translation factor. Cell 118, 465–475 (2004).

Zhu, J. et al. Crystal structures of complexes containing domains from two viral internal ribosome entry site (IRES) RNAs bound to the 70S ribosome. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 108, 1839–1844 (2011).

Butcher, S. E. & Jan, E. tRNA-mimicry in IRES-mediated translation and recoding. RNA Biol. 13, 1068–1074 (2016).

Costantino, D. A., Pfingsten, J. S., Rambo, R. P. & Kieft, J. S. tRNA-mRNA mimicry drives translation initiation from a viral IRES. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 15, 57–64 (2007).

Fernandez, J., Yaman, I., Sarnow, P., Snider, M. D. & Hatzoglou, M. Regulation of internal ribosomal entry site-mediated translation by phosphorylation of the translation initiation factor eIF2α. J. Biol. Chem. 277, 19198–19205 (2002).

Muhs, M. et al. Cryo-EM of ribosomal 80S complexes with termination factors reveals the translocated cricket paralysis virus IRES. Mol. Cell 57, 422–432 (2015).

Fernández, I. S., Bai, X.-C., Murshudov, G., Scheres, S. H. W. & Ramakrishnan, V. Initiation of translation by cricket paralysis virus IRES requires its translocation in the ribosome. Cell 157, 823–831 (2014).

Ruehle, M. D. et al. A dynamic RNA loop in an IRES affects multiple steps of elongation factor-mediated translation initiation. eLife 4, e08146 (2015).

Abeyrathne, P. D., Koh, C. S., Grant, T., Grigorieff, N. & Korostelev, A. A. Ensemble cryo-EM uncovers inchworm-like translocation of a viral IRES through the ribosome. eLife 5, e14874 (2016). Using cryo-EM, this study uncovers the structures of multiple states of class 4 IRES translation initiation events, showing that conformational rearrangements allow it to transit the ribosome during translation initiation.

Martínez-Salas, E., Francisco-Velilla, R., Fernandez-Chamorro, J., Lozano, G. & Diaz-Toledano, R. Picornavirus IRES elements: RNA structure and host protein interactions. Virus Res. 206, 62–73 (2015).

Robert, F. et al. Initiation of protein synthesis by hepatitis C virus is refractory to reduced eIF2.GTP.Met-tRNA(i)(Met) ternary complex availability. Mol. Biol. Cell 17, 4632–4644 (2006).

Jaafar, Z. A., Oguro, A., Nakamura, Y. & Kieft, J. S. Translation initiation by the hepatitis C virus IRES requires eIF1A and ribosomal complex remodeling. eLife 5, e21198 (2016).

Terenin, I. M., Dmitriev, S. E., Andreev, D. E. & Shatsky, I. N. Eukaryotic translation initiation machinery can operate in a bacterial-like mode without eIF2. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 15, 836–841 (2008). This paper presents a mechanistic study of the ability of the HCV IRES to recruit tRNA to the 40S subunit without using eIF2.

Pestova, T. V., de Breyne, S., Pisarev, A. V., Abaeva, I. S. & Hellen, C. U. eIF2-dependent and eIF2-independent modes of initiation on the CSFV IRES: a common role of domain II. EMBO J. 27, 1060–1072 (2008).

Quade, N., Boehringer, D., Leibundgut, M., van den Heuvel, J. & Ban, N. Cryo-EM structure of hepatitis C virus IRES bound to the human ribosome at 3.9-Å resolution. Nat. Commun. 6, 7646 (2015).

Yamamoto, H. et al. Structure of the mammalian 80S initiation complex with initiation factor 5B on HCV-IRES RNA. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 21, 721–727 (2014). This study presents a cryo-EM structure offering key insights into the later steps in HCV IRES-mediated translation initiation and functions of eIF5B after subunit joining.

Hashem, Y. et al. Hepatitis-C-virus-like internal ribosome entry sites displace eIF3 to gain access to the 40S subunit. Nature 503, 539–543 (2013).

Khawaja, A., Vopalensky, V. & Pospisek, M. Understanding the potential of hepatitis C virus internal ribosome entry site domains to modulate translation initiation via their structure and function. Wiley Interdiscip. Rev. RNA 6, 211–224 (2015).

Pestova, T. V., Shatsky, I. N., Fletcher, S. P., Jackson, R. J. & Hellen, C. U. A prokaryotic-like mode of cytoplasmic eukaryotic ribosome binding to the initiation codon during internal translation initiation of hepatitis C and classical swine fever virus RNAs. Genes Dev. 12, 67–83 (1998). This seminal study establishes direct binding of the HCV (and related IRESs) to the 40S subunit and the set of factors needed for initiation to occur on the IRES.

Kieft, J. S., Zhou, K., Jubin, R. & Doudna, J. A. Mechanism of ribosome recruitment by hepatitis C IRES RNA. RNA 7, 194–206 (2001).

Filbin, M. E., Vollmar, B. S., Shi, D., Gonen, T. & Kieft, J. S. HCV IRES manipulates the ribosome to promote the switch from translation initiation to elongation. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 20, 150–158 (2012).

Filbin, M. E. & Kieft, J. S. HCV IRES domain IIb affects the configuration of coding RNA in the 40S subunit’s decoding groove. RNA 17, 1258–1273 (2011).

Locker, N., Easton, L. E. & Lukavsky, P. J. HCV and CSFV IRES domain II mediate eIF2 release during 80S ribosome assembly. EMBO J. 26, 795–805 (2007).

Spahn, C. M. et al. Hepatitis C virus IRES RNA-induced changes in the conformation of the 40S ribosomal subunit. Science 291, 1959–1962 (2001). This study provides the first 3D view of an IRES bound to a ribosomal subunit, establishing this IRES as an active manipulator of ribosome structure.

Kim, J. H., Park, S. M., Park, J. H., Keum, S. J. & Jang, S. K. eIF2A mediates translation of hepatitis C viral mRNA under stress conditions. EMBO J. 30, 2454–2464 (2011).

Skabkin, M. A. et al. Activities of Ligatin and MCT-1/DENR in eukaryotic translation initiation and ribosomal recycling. Genes Dev. 24, 1787–1801 (2010).

Dmitriev, S. E. et al. GTP-independent tRNA delivery to the ribosomal P-site by a novel eukaryotic translation factor. J. Biol. Chem. 285, 26779–26787 (2010).

de Breyne, S., Yu, Y., Pestova, T. V. & Hellen, C. U. T. Factor requirements for translation initiation on the Simian picornavirus internal ribosomal entry site. RNA 14, 367–380 (2007). This detailed biochemical study of a class 3 IRES suggests the possibility of factor-independent and initiator tRNA delivery.

King, H. A., Cobbold, L. C. & Willis, A. E. The role of IRES trans-acting factors in regulating translation initiation. Biochem. Soc. Trans. 38, 1581–1586 (2010).

Lozano, G. & Martínez-Salas, E. Structural insights into viral IRES-dependent translation mechanisms. Curr. Opin. Virol. 12, 113–120 (2015).

Meurs, E. F. et al. Constitutive expression of human double-stranded RNA-activated p68 kinase in murine cells mediates phosphorylation of eukaryotic initiation factor 2 and partial resistance to encephalomyocarditis virus growth. J. Virol. 66, 5805–5814 (1992).

White, J. P., Reineke, L. C. & Lloyd, R. E. Poliovirus switches to an eIF2-independent mode of translation during infection. J. Virol. 85, 8884–8893 (2011).

Kafasla, P. et al. Polypyrimidine tract binding protein stabilizes the encephalomyocarditis virus IRES structure via binding multiple sites in a unique orientation. Mol. Cell 34, 556–568 (2009). This article provides an illustration of the paradigm that ITAFs affect IRES structure to allow translation machinery to bind.

Borovjagin, A., Pestova, T. & Shatsky, I. Pyrimidine tract binding protein strongly stimulates in vitro encephalomyocarditis virus RNA translation at the level of preinitiation complex formation. FEBS Lett. 351, 299–302 (1994).

Kafasla, P., Morgner, N., Robinson, C. V. & Jackson, R. J. Polypyrimidine tract-binding protein stimulates the poliovirus IRES by modulating eIF4G binding. EMBO J. 29, 3710–3722 (2010).

Sweeney, T. R., Abaeva, I. S., Pestova, T. V. & Hellen, C. U. T. The mechanism of translation initiation on type 1 picornavirus IRESs. EMBO J. 33, 76–92 (2013).

Fernandez-Miragall, O., Ramos, R., Ramajo, J. & Martnez-Salas, E. Evidence of reciprocal tertiary interactions between conserved motifs involved in organizing RNA structure essential for internal initiation of translation. RNA 12, 223–234 (2005).

Fernández, N. et al. Structural basis for the biological relevance of the invariant apical stem in IRES-mediated translation. Nucleic Acids Res. 39, 8572–8585 (2011).

Fernandez-Miragall, O. & Martnez-Salas, E. Structural organization of a viral IRES depends on the integrity of the GNRA motif. RNA 9, 1333–1344 (2003).

Kolupaeva, V. G., Pestova, T. V., Hellen, C. U. & Shatsky, I. N. Translation eukaryotic initiation factor 4G recognizes a specific structural element within the internal ribosome entry site of encephalomyocarditis virus RNA. J. Biol. Chem. 273, 18599–18604 (1998).

de Quinto, S. L., Lafuente, E. & Martnez-Salas, E. IRES interaction with translation initiation factors: functional characterization of novel RNA contacts with eIF3, eIF4B, and eIF4GII. RNA 7, 1213–1226 (2001).

Kaminski, A., Belsham, G. J. & Jackson, R. J. Translation of encephalomyocarditis virus RNA: parameters influencing the selection of the internal initiation site. EMBO J. 13, 1673–1681 (1994).

Lopez de Quinto, S. & Martinez-Salas, E. Involvement of the aphthovirus RNA region located between the two functional AUGs in start codon selection. Virology 255, 324–336 (1999).

Pilipenko, E. V. et al. Prokaryotic-like cis elements in the cap-independent internal initiation of translation on picornavirus RNA. Cell 68, 119–131 (1992).

Pelletier, J. & Sonenberg, N. Internal initiation of translation of eukaryotic mRNA directed by a sequence derived from poliovirus RNA. Nature 334, 320–325 (1988). This study is the first to characterize the existence of an IRES in poliovirus and report the first methods used to validate IRES function.

Du, Z., Ulyanov, N. B., Yu, J., Andino, R. & James, T. L. NMR structures of loop B RNAs from the stem-loop IV domain of the enterovirus internal ribosome entry site: a single C to U substitution drastically changes the shape and flexibility of RNA. Biochemistry 43, 5757–5771 (2004).

Imai, S., Kumar, P., Hellen, C. U., D’Souza, V. M. & Wagner, G. An accurately preorganized IRES RNA structure enables eIF4G capture for initiation of viral translation. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 23, 859–864 (2016).

Abaeva, I. S., Pestova, T. V. & Hellen, C. U. T. Attachment of ribosomal complexes and retrograde scanning during initiation on the Halastavi árva virus IRES. Nucleic Acids Res. 44, 2362–2377 (2016). This paper presents a description of an IRES that uses an unusual form of retrograde scanning to position a start codon.

Plank, T.-D. M., Whitehurst, J. T. & Kieft, J. S. Cell type specificity and structural determinants of IRES activity from the 5' leaders of different HIV-1 transcripts. Nucleic Acids Res. 41, 6698–6714 (2013).

Ohlmann, T., Mengardi, C. & Lopez-Lastra, M. Translation initiation of the HIV-1 mRNA. Translation 2, e960242 (2014).

Smirnova, V. V. et al. Does HIV-1 mRNA 5'-untranslated region bear an internal ribosome entry site? Biochimie 121, 228–237 (2015).

Murat, P. et al. G-Quadruplexes regulate Epstein-Barr virus-encoded nuclear antigen 1 mRNA translation. Nat. Chem. Biol. 10, 358–364 (2014).

Caliskan, N., Peske, F. & Rodnina, M. V. Changed in translation: mRNA recoding by -1 programmed ribosomal frameshifting. Trends Biochem. Sci. 40, 265–274 (2015).

Dinman, J. D. Mechanisms and implications of programmed translational frameshifting. Wiley Interdiscip. Rev. RNA 3, 661–673 (2012).

Plant, E. P. & Dinman, J. D. Comparative study of the effects of heptameric slippery site composition on -1 frameshifting among different eukaryotic systems. RNA 12, 666–673 (2006). This study provides a systematic analysis of the contribution of the ‘slippery’ sequence to frameshifting and how that contribution varies between sequences and among ribosomes from distinct eukaryotic sources.

Ishimaru, D. et al. RNA dimerization plays a role in ribosomal frameshifting of the SARS coronavirus. Nucleic Acids Res. 41, 2594–2608 (2013).

Marcheschi, R. J., Staple, D. W. & Butcher, S. E. Programmed ribosomal frameshifting in SIV is induced by a highly structured RNA stem-loop. J. Mol. Biol. 373, 652–663 (2007).

Gaudin, C. et al. Structure of the RNA signal essential for translational frameshifting in HIV-1. J. Mol. Biol. 349, 1024–1035 (2005).

Biswas, P., Jiang, X., Pacchia, A. L., Dougherty, J. P. & Peltz, S. W. The human immunodeficiency virus type 1 ribosomal frameshifting site is an invariant sequence determinant and an important target for antiviral therapy. J. Virol. 78, 2082–2087 (2004).

Gao, F. & Simon, A. E. Multiple cis-acting elements modulate programmed -1 ribosomal frameshifting in pea enation mosaic virus. Nucleic Acids Res. 44, 878–895 (2016). This article provides a fascinating example of how a combination of folded RNAs can be used to create a complex regulation strategy.

Moomau, C., Musalgaonkar, S., Khan, Y. A., Jones, J. E. & Dinman, J. D. Structural and functional characterization of programmed ribosomal frameshift signals in West Nile virus strains reveals high structural plasticity among cis-acting rna elements. J. Biol. Chem. 291, 15788–15795 (2016).

Ritchie, D. B., Foster, D. A. & Woodside, M. T. Programmed -1 frameshifting efficiency correlates with RNA pseudoknot conformational plasticity, not resistance to mechanical unfolding. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 109, 16167–16172 (2012).

Mouzakis, K. D., Lang, A. L., Vander Meulen, K. A., Easterday, P. D. & Butcher, S. E. HIV-1 frameshift efficiency is primarily determined by the stability of base pairs positioned at the mRNA entrance channel of the ribosome. Nucleic Acids Res. 41, 1901–1913 (2013). This study demonstrates the importance of thermodynamic stability in certain parts of an RNA element to create a specific translation recoding event.

Chen, J. et al. Dynamic pathways of -1 translational frameshifting. Nature 512, 328–332 (2014). This paper presents a quantitative cutting-edge biophysical study of the mechanics of frameshifting on bacterial ribosomes.

Takyar, S., Hickerson, R. P. & Noller, H. F. mRNA helicase activity of the ribosome. Cell 120, 49–58 (2005).

Li, Y. et al. Transactivation of programmed ribosomal frameshifting by a viral protein. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 111, E2172–E2181 (2014).

Fang, Y. et al. Efficient -2 frameshifting by mammalian ribosomes to synthesize an additional arterivirus protein. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 109, E2920–E2928 (2012).

Napthine, S. et al. A novel role for poly(C) binding proteins in programmed ribosomal frameshifting. Nucleic Acids Res. 44, 5491–5503 (2016).

Finch, L. K. et al. Characterization of ribosomal frameshifting in theiler’s murine encephalomyelitis virus. J. Virol. 89, 8580–8589 (2015).

Napthine, S. et al. Protein-directed ribosomal frameshifting temporally regulates gene expression. Nat. Commun. 8, 15582 (2017).

Loughran, G., Firth, A. E. & Atkins, J. F. Ribosomal frameshifting into an overlapping gene in the 2B-encoding region of the cardiovirus genome. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 108, E1111–E1119 (2011).

Tork, S., Hatin, I., Rousset, J. P. & Fabret, C. The major 5' determinant in stop codon read-through involves two adjacent adenines. Nucleic Acids Res. 32, 415–421 (2004).

Namy, O., Hatin, I. & Rousset, J. P. Impact of the six nucleotides downstream of the stop codon on translation termination. EMBO Rep. 2, 787–793 (2001).

Cassan, M. & Rousset, J. P. UAG readthrough in mammalian cells: effect of upstream and downstream stop codon contexts reveal different signals. BMC Mol. Biol. 2, 3 (2001).

Harrell, L., Melcher, U. & Atkins, J. F. Predominance of six different hexanucleotide recoding signals 3' of read-through stop codons. Nucleic Acids Res. 30, 2011–2017 (2002).

Skuzeski, J. M., Nichols, L. M., Gesteland, R. F. & Atkins, J. F. The signal for a leaky UAG stop codon in several plant viruses includes the two downstream codons. J. Mol. Biol. 218, 365–373 (1991).

Firth, A. E., Wills, N. M., Gesteland, R. F. & Atkins, J. F. Stimulation of stop codon readthrough: frequent presence of an extended 3' RNA structural element. Nucleic Acids Res. 39, 6679–6691 (2011).

Napthine, S., Yek, C., Powell, M. L., Brown, T. D. K. & Brierley, I. Characterization of the stop codon readthrough signal of Colorado tick fever virus segment 9 RNA. RNA 18, 241–252 (2011).

Houck-Loomis, B. et al. An equilibrium-dependent retroviral mRNA switch regulates translational recoding. Nature 480, 561–564 (2011).

Wills, N. M., Gesteland, R. F. & Atkins, J. F. Evidence that a downstream pseudoknot is required for translational read-through of the Moloney murine leukemia virus gag stop codon. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 88, 6991–6995 (1991).

Cimino, P. A., Nicholson, B. L., Wu, B., Xu, W. & White, K. A. Multifaceted regulation of translational readthrough by RNA replication elements in a tombusvirus. PLOS Pathog. 7, e1002423 (2011).

Kuhlmann, M. M., Chattopadhyay, M., Stupina, V. A., Gao, F. & Simon, A. E. An RNA element that facilitates programmed ribosomal readthrough in turnip crinkle virus adopts multiple conformations. J. Virol. 90, 8575–8591 (2016). This paper provides an example of how conformational changes in RNA influence biological function.

Beier, H. & Grimm, M. Misreading of termination codons in eukaryotes by natural nonsense suppressor tRNAs. Nucleic Acids Res. 29, 4767–4782 (2001).

Meyers, G. Characterization of the sequence element directing translation reinitiation in RNA of the calicivirus rabbit hemorrhagic disease virus. J. Virol. 81, 9623–9632 (2007).

Luttermann, C. & Meyers, G. A bipartite sequence motif induces translation reinitiation in feline calicivirus RNA. J. Biol. Chem. 282, 7056–7065 (2007).

McCormick, C. J., Salim, O., Lambden, P. R. & Clarke, I. N. Translation termination reinitiation between open reading frame 1 (ORF1) and ORF2 enables capsid expression in a bovine norovirus without the need for production of viral subgenomic RNA. J. Virol. 82, 8917–8921 (2008).

Luttermann, C. & Meyers, G. The importance of inter- and intramolecular base pairing for translation reinitiation on a eukaryotic bicistronic mRNA. Genes Dev. 23, 331–344 (2009).

Zinoviev, A., Hellen, C. U. T. & Pestova, T. V. Multiple mechanisms of reinitiation on bicistronic calicivirus mRNAs. Mol. Cell 57, 1059–1073 (2015).

Nicholson, B. L. & White, K. A. 3' cap-independent translation enhancers of positive-strand RNA plant viruses. Curr. Opin. Virol. 1, 373–380 (2011).

Simon, A. E. & Miller, W. A. 3' cap-independent translation enhancers of plant viruses. Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 67, 21–42 (2013).

Miras, M., Miller, W. A., Truniger, V. & Aranda, M. A. Non-canonical translation in plant RNA viruses. Front. Plant Sci. 8, 494 (2017). This article reports on a recent discovery of a novel class of viral 3 '- CITE shared between viral families by recombination.

Truniger, V., Miras, M. & Aranda, M. A. Structural and functional diversity of plant virus 3'-cap-independent translation enhancers (3'-CITEs). Front. Plant. Sci. 8, 2047 (2017). This paper provides an excellent recent review of 3′ -CITE diversity and structure.

Guo, L., Allen, E. & Miller, W. A. Structure and function of a cap-independent translation element that functions in either the 3' or the 5' untranslated region. RNA 6, 1808–1820 (2000).

Guo, L., Allen, E. M. & Miller, W. A. Base-pairing between untranslated regions facilitates translation of uncapped, nonpolyadenylated viral RNA. Mol. Cell 7, 1103–1109 (2001).

Rakotondrafara, A. M., Polacek, C., Harris, E. & Miller, W. A. Oscillating kissing stem-loop interactions mediate 5' scanning-dependent translation by a viral 3'-cap-independent translation element. RNA 12, 1893–1906 (2006).

Nicholson, B. L., Wu, B., Chevtchenko, I. & White, K. A. Tombusvirus recruitment of host translational machinery via the 3' UTR. RNA 16, 1402–1419 (2010).

Wang, S., Browning, K. S. & Miller, W. A. A viral sequence in the 3'-untranslated region mimics a 5' cap in facilitating translation of uncapped mRNA. EMBO J. 16, 4107–4116 (1997).

Gazo, B. M., Murphy, P., Gatchel, J. R. & Browning, K. S. A novel interaction of Cap-binding protein complexes eukaryotic initiation factor (eIF) 4F and eIF(iso)4F with a region in the 3'-untranslated region of satellite tobacco necrosis virus. J. Biol. Chem. 279, 13584–13592 (2004).

Miller, W. A., Wang, Z. & Treder, K. The amazing diversity of cap-independent translation elements in the 3'-untranslated regions of plant viral RNAs. Biochem. Soc. Trans. 35, 1629–1633 (2007).

Meulewaeter, F. et al. Conservation of RNA structures enables TNV and BYDV 5′ and 3' elements to cooperate synergistically in cap-independent translation. Nucleic Acids Res. 32, 1721–1730 (2004).

Fan, Q., Treder, K. & Miller, W. A. Untranslated regions of diverse plant viral RNAs vary greatly in translation enhancement efficiency. Biochem. Soc. Trans. 12, 22 (2012).

Wang, S. & Miller, W. A. A sequence located 4.5 to 5 kilobases from the 5' end of the barley yellow dwarf virus (PAV) genome strongly stimulates translation of uncapped mRNA. J. Biol. Chem. 270, 13446–13452 (1995).

Wang, Z., Kraft, J. J., Hui, A. Y. & Miller, W. A. Structural plasticity of Barley yellow dwarf virus-like cap-independent translation elements in four genera of plant viral RNAs. Virology 402, 177–186 (2010).

Das Sharma, S., Kraft, J. J., Miller, W. A. & Goss, D. J. Recruitment of the 40S ribosome subunit to the 3'-untranslated region (UTR) of a viral mRNA, via the eIF4 complex, facilitates cap-independent translation. J. Biol. Chem. 290, 11268–11281 (2015).

Kraft, J. J., Treder, K., Peterson, M. S. & Miller, W. A. Cation-dependent folding of 3' cap-independent translation elements facilitates interaction of a 17-nucleotide conserved sequence with eIF4G. Nucleic Acids Res. 41, 3398–3413 (2013).

Zhao, P., Liu, Q., Miller, W. A. & Goss, D. J. Eukaryotic translation initiation factor 4G (eIF4G) coordinates interactions with eIF4A, eIF4B, and eIF4E in binding and translation of the barley yellow dwarf virus 3' cap-independent translation element (BTE). J. Biol. Chem. 292, 5921–5931 (2017). This article presents an in-depth quantitative exploration of the interactions underlying recruitment of translation factors to a 3 ' -CITE.

Batten, J. S., Desvoyes, B., Yamamura, Y. & Scholthof, K.-B. G. A translational enhancer element on the 3′-proximal end of the Panicum mosaic virus genome. FEBS Lett. 580, 2591–2597 (2006).

Wang, Z., Treder, K. & Miller, W. A. Structure of a viral cap-independent translation element that functions via high affinity binding to the eIF4E subunit of eIF4F. J. Biol. Chem. 284, 14189–14202 (2009).

Liu, Q. & Goss, D. J. Understanding the role of pea enation mosaic virus mRNA 3′ untranslated region in translation initiation [abstract]. FASEB J. 28 (Suppl. 1), 566.5 (2014).

Wang, Z., Parisien, M., Scheets, K. & Miller, W. A. The cap-binding translation initiation factor, eIF4E, binds a pseudoknot in a viral cap-independent translation element. Structure 19, 868–880 (2011). This study provides a detailed characterization of a 3′ -CITE that binds eIF4E, with a compelling structural model for how this occurs.

Stupina, V. A. et al. The 3′ proximal translational enhancer of Turnip crinkle virus binds to 60S ribosomal subunits. RNA 14, 2379–2393 (2008).

McCormack, J. C. et al. Structural domains within the 3′ untranslated region of Turnip crinkle virus. J. Virol. 82, 8706–8720 (2008).

Stupina, V. A., Yuan, X., Meskauskas, A., Dinman, J. D. & Simon, A. E. Ribosome binding to a 5′ translational enhancer is altered in the presence of the 3′ untranslated region in cap-independent translation of turnip crinkle virus. J. Virol. 85, 4638–4653 (2011).

Gao, F. & Simon, A. E. Differential use of 3′CITEs by the subgenomic RNA of Pea enation mosaic virus 2. Virology 510, 194–204 (2017).

Gao, F., Kasprzak, W. K., Szarko, C., Shapiro, B. A. & Simon, A. E. The 3′ untranslated region of pea enation mosaic virus contains two T-shaped, ribosome-binding, cap-independent translation enhancers. J. Virol. 88, 11696–11712 (2014). This paper presents an illustration of how plant virus 3′ -CITEs can exist in multiple copies as part of a complex translation initiation regulation strategy.

Du, Z., Alekhina, O. M., Vassilenko, K. S. & Simon, A. E. Concerted action of two 3′ cap-independent translation enhancers increases the competitive strength of translated viral genomes. Nucleic Acids Res. 45, 9558–9572 (2017). Related to reference 152, this study shows how a combination of 3′ -CITEs can work together in a complex way to increase the success of the virus.

Zuo, X. et al. Solution structure of the cap-independent translational enhancer and ribosome-binding element in the 3′ UTR of turnip crinkle virus. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 107, 1385–1390 (2010).

Yuan, X., Shi, K., Meskauskas, A. & Simon, A. E. The 3′ end of Turnip crinkle virus contains a highly interactive structure including a translational enhancer that is disrupted by binding to the RNA-dependent RNA polymerase. RNA 15, 1849–1864 (2009).

Le, M. T. et al. Folding behavior of a T-shaped, ribosome-binding translation enhancer implicated in a wide-spread conformational switch. eLife 6, e22883 (2017).

Dreher, T. W. Viral tRNAs and tRNA-like structures. Wiley Interdiscip. Rev. RNA 1, 402–414 (2010).

Dreher, T. W., Uhlenbeck, O. C. & Browning, K. S. Quantitative assessment of EF-1alpha. GTP binding to aminoacyl-tRNAs, aminoacyl-viral RNA, and tRNA shows close correspondence to the RNA binding properties of EF-Tu. J. Biol. Chem. 274, 666–672 (1999). This quantitative assessment of the binding of a viral TLS to eIF1A demonstrates endogenous tRNA-like affinity and supports its importance to the virus.

Colussi, T. M. et al. The structural basis of transfer RNA mimicry and conformational plasticity by a viral RNA. Nature 511, 366–369 (2014). This article presents a crystal structure of a viral TLS showing an overall tRNA-like but structurally distinct fold that presents key insights into aminoacylation as well as accessibility for replication.

Hammond, J. A., Rambo, R. P. & Kieft, J. S. Multi-domain packing in the aminoacylatable 3′ end of a plant viral RNA. J. Mol. Biol. 399, 450–463 (2010).

Barends, S., Bink, H. H., van den Worm, S. H., Pleij, C. W. & Kraal, B. Entrapping ribosomes for viral translation: tRNA mimicry as a molecular Trojan horse. Cell 112, 123–129 (2003).

Matsuda, D. & Dreher, T. W. Cap- and initiator tRNA-dependent initiation of TYMV polyprotein synthesis by ribosomes: evaluation of the Trojan horse model for TYMV RNA translation. RNA 13, 129–137 (2006).

Shen, L. X. & Tinoco, I. Jr. The structure of an RNA pseudoknot that causes efficient frameshifting in mouse mammary tumor virus. J. Mol. Biol. 247, 963–978 (1995).

Chattopadhyay, M., Shi, K., Yuan, X. & Simon, A. E. Long-distance kissing loop interactions between a 3′ proximal Y-shaped structure and apical loops of 5′ hairpins enhance translation of Saguaro cactus virus. Virology 417, 113–125 (2011).

Acknowledgements

The authors thank D. Costantino for critical reading of this manuscript. Viral RNA research in the Kieft laboratory is supported by US National Institutes of Health grants R35GM118070, R21AI129569, R01AI133348 and P01AI120943 (J.S.K.).

Reviewer information

Nature Reviews Microbiology thanks C. Hellen, A. Simon, and other anonymous reviewer(s), for their contribution to the peer review of this work.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Z.A.J. researched data for the article. Z.A.J. and J.S.K. wrote the manuscript together.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Related links

RCSB Protein Databank: http://www.rcsb.org/pdb/home/home.do

Glossary

- Eukaryotic initiation factors

-

(eIFs). Protein factors or complexes found in eukaryotes, the primary function of which is in stabilizing the formation of ribosome-containing complexes and properly positioning these complexes at the start codon during translation initiation.

- Innate immune response

-

A set of immediate cellular responses that detects infection and then triggers a variety of pathways designed to limit infection. This response is not specific to the identity of the infectious agent and includes molecular events that affect translation (such as phosphorylation of the α-subunit of eukaryotic initiation factor 2).

- 5′ end

-

The end of a nucleic acid that terminates in a functional group attached to the fifth carbon of a ribose sugar.

- 3′ end

-

The end of a nucleic acid that terminates in a functional group attached to the third carbon of a ribose sugar.

- Canonical translation initiation

-

A eukaryotic-specific translation initiation pathway that operates on an mRNA that has been post-transcriptionally modified to include an extra methylated nucleotide at its 5′ end. Binding of this modified nucleotide by a protein begins the process of initiation.

- Initiator tRNA

-

A structurally and functionally distinct tRNA responsible for delivering the first amino acid (methionine) to the ribosome. It binds in the P site of the ribosome, has an anticodon complementary to AUG and is used for initiation of the vast majority of proteins. It is not used during the elongation phase of translation.

- UTRs

-

Portions of an mRNA outside of its protein-coding region. These often contain sequences or structures important for the regulation of mRNA translation, localization or decay.

- Kozak sequence

-

Sequence of RNA around a translation start codon that determines the ‘context strength’ of the AUG and thus the degree to which that start codon is used to begin translation.

- Ribosome profiling

-

A next-generation sequencing-based method to determine, at single-nucleotide resolution, the position of ribosomes on mRNAs on a transcriptome-wide scale.

- Subgenomic RNA

-

(sgRNA). A viral RNA (generally transcribed from the viral genomic RNA) that is important for virus biology but does not contain the full viral genomic RNA sequence.

- eIF2α phosphorylation

-

Eukaryotic initiation factor 2 (eIF2) delivers the initiator tRNA to the ribosome during initiation. Its α-subunit can be phosphorylated as a response to various cellular stresses, including viral infection. This event in effect ‘deactivates’ the factor, which overall depresses translation that depends on eIF2.

- RNA stem-loop

-

An RNA secondary structure feature formed when a single strand of RNA folds back to base pair with itself, forming a loop at its apex. Also referred to as an RNA hairpin.

- P site

-

The second tRNA binding site within the ribosome. After peptide bond formation, translocation moves the A-site tRNA (which is linked to the peptide chain) into the P site.

- RNA pseudoknots

-

RNA structural elements formed when nucleotides in a stem-loop pair with regions outside the loop, often giving rise to a thermodynamically stable compact structure. There are many types of pseudoknots.

- Codon–anticodon interaction

-

A stable interaction between an mRNA codon nucleotide triplet and the corresponding nucleotides in the anticodon stem-loop of a tRNA.

- A site

-

The first tRNA binding site within the ribosome. Here, mRNA codons are decoded by tRNAs during elongation.

- Translocation

-

The simultaneous movement of mRNA and tRNA on the ribosome after the formation of a new peptide bond (during elongation). The mRNA moves by three bases (one codon), accompanied by movement of the A-site tRNA to the P site and the P-site tRNA to the E site. The result is the next codon to be decoded in the A site, where it can be recognized by a tRNA.

- Decoding groove

-

The part of the small ribosomal subunit that accommodates and orients mRNA codons as they are decoded by cognate tRNAs.

- IRES trans-acting factors

-

(ITAFs). Proteins that are not part of the canonical set of eukaryotic initiation factors but enhance or are required for translation initiation from a specific internal ribosome entry site.

- Polypyrimidine tract

-

A stretch of an RNA sequence containing a high percentage of cytosine and uracil bases.

- GNRA tetraloops

-

A type of RNA hairpin loop in which the loop contains four nucleotides of the pattern ‘GNRA’; these are stable structures that often are involved in long-range RNA tertiary interactions.

- G-quadruplex structures

-

Stable RNA motifs in which guanine residues form tetrads through extensive hydrogen bonding; two or more tetrad structures may base stack to form higher-order quadruplexes.

- Suppressor tRNA

-

A type of tRNA molecule that recognizes a stop codon and delivers an amino acid to the ribosome in lieu of terminating translation.

- eIF4F complex

-

A complex of three eukaryotic initiation factors (eIFs) (eIF4E, eIF4G and eIF4A) responsible for recognizing the 5′ capped end of an mRNA and recruiting a ribosome for subsequent translation.

- T-shaped structures

-

(TSSs). Sites of 3′ cap-independent translation elements that are proposed to form a secondary structure that looks like a ‘T’.

- Kissing-loop interactions

-

Long-distance base pairing between the loop bases of two RNA stem-loops. This interaction can occur between elements very distal in sequence.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Jaafar, Z.A., Kieft, J.S. Viral RNA structure-based strategies to manipulate translation. Nat Rev Microbiol 17, 110–123 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41579-018-0117-x

Published:

Version of record:

Issue date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41579-018-0117-x

This article is cited by

-

The pathogenesis of foot-and-mouth disease virus: current understandings and knowledge gaps

Veterinary Research (2025)

-

Structural insights into dynamics of the BMV TLS aminoacylation

Nature Communications (2025)

-

Structural basis for 3C and 3CD recruitment by enteroviral genomes during negative-strand RNA synthesis

Nature Communications (2025)

-

RNA sample optimization for cryo-EM analysis

Nature Protocols (2025)

-

TISCalling: leveraging machine learning to identify translational initiation sites in plants and viruses

Plant Molecular Biology (2025)