Abstract

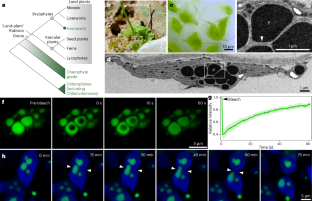

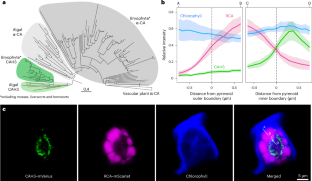

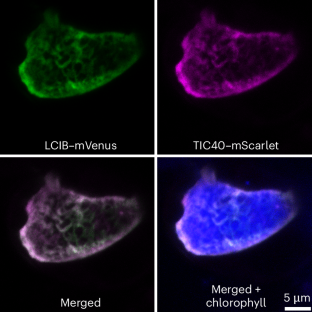

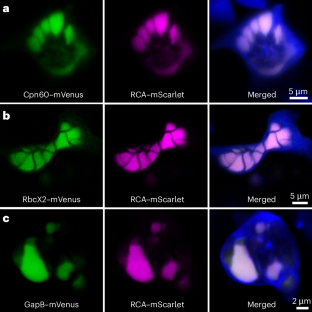

Pyrenoid-based CO2-concentrating mechanisms (pCCMs) turbocharge photosynthesis by saturating CO2 around Rubisco. Hornworts are the only land plants with a pCCM. Owing to their closer relationship to crops, hornworts could offer greater translational potential than the green alga Chlamydomonas, the traditional model for studying pCCMs. Here we report a thorough investigation of a hornwort pCCM using the emerging model Anthoceros agrestis. The pyrenoids in A. agrestis exhibit liquid-like properties similar to those in Chlamydomonas, but they differ by lacking starch sheaths and being enclosed by multiple thylakoids. We found that the core pCCM components in Chlamydomonas, including BST, LCIB and CAH3, are conserved in A. agrestis and probably have similar functions on the basis of their subcellular localizations. The underlying chassis for concentrating CO2 might therefore be shared between hornworts and Chlamydomonas, and ancestral to land plants. Our study presents a spatial model for a pCCM in a land plant, paving the way for future biochemical and genetic investigations.

This is a preview of subscription content, access via your institution

Access options

Access Nature and 54 other Nature Portfolio journals

Get Nature+, our best-value online-access subscription

$32.99 / 30 days

cancel any time

Subscribe to this journal

Receive 12 digital issues and online access to articles

$119.00 per year

only $9.92 per issue

Buy this article

- Purchase on SpringerLink

- Instant access to the full article PDF.

USD 39.95

Prices may be subject to local taxes which are calculated during checkout

Similar content being viewed by others

Data availability

Newly generated proteomics data have been deposited in MassIVE, under accession no. MSV000095322. The gene expression data can be found in the NCBI Sequence Read Archive under BioProject no. PRJNA996135. The protein structure used for aiding Rubisco antibody design can be found in the Protein Data Bank (accession no. 2V63).

References

Bar-On, Y. M. & Milo, R. The global mass and average rate of Rubisco. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 116, 4738–4743 (2019).

Ellis, R. J. The most abundant protein in the world. Trends Biochem. Sci. 4, 241–244 (1979).

Leegood, R. C. A welcome diversion from photorespiration. Nat. Biotechnol. 25, 539–540 (2007).

Long, S. P., Zhu, X.-G., Naidu, S. L. & Ort, D. R. Can improvement in photosynthesis increase crop yields? Plant Cell Environ. 29, 315–330 (2006).

Griffiths, H., Meyer, M. T. & Rickaby, R. E. M. Overcoming adversity through diversity: aquatic carbon concentrating mechanisms. J. Exp. Bot. 68, 3689–3695 (2017).

Badger, M. R. & Price, G. D. CO2 concentrating mechanisms in cyanobacteria: molecular components, their diversity and evolution. J. Exp. Bot. 54, 609–622 (2003).

Mackinder, L. C. M. et al. A repeat protein links Rubisco to form the eukaryotic carbon-concentrating organelle. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 113, 5958–5963 (2016).

Freeman Rosenzweig, E. S. et al. The eukaryotic CO2-concentrating organelle is liquid-like and exhibits dynamic reorganization. Cell 171, 148–162.e19 (2017).

Wunder, T., Cheng, S. L. H., Lai, S.-K., Li, H.-Y. & Mueller-Cajar, O. The phase separation underlying the pyrenoid-based microalgal Rubisco supercharger. Nat. Commun. 9, 5076 (2018).

He, S., Crans, V. L. & Jonikas, M. C. The pyrenoid: the eukaryotic CO2-concentrating organelle. Plant Cell 35, 3236–3259 (2023).

Ramazanov, Z. et al. The induction of the CO–-concentrating mechanism is correlated with the formation of the starch sheath around the pyrenoid of Chlamydomonas reinhardtii. Planta 195, 210–216 (1994).

Itakura, A. K. et al. A Rubisco-binding protein is required for normal pyrenoid number and starch sheath morphology in Chlamydomonas reinhardtii. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 116, 18445–18454 (2019).

Fei, C., Wilson, A. T., Mangan, N. M., Wingreen, N. S. & Jonikas, M. C. Modelling the pyrenoid-based CO2-concentrating mechanism provides insights into its operating principles and a roadmap for its engineering into crops. Nat. Plants 8, 583–595 (2022).

McGrath, J. M. & Long, S. P. Can the cyanobacterial carbon-concentrating mechanism increase photosynthesis in crop species? A theoretical analysis. Plant Physiol. 164, 2247–2261 (2014).

Yin, X. & Struik, P. C. Can increased leaf photosynthesis be converted into higher crop mass production? A simulation study for rice using the crop model GECROS. J. Exp. Bot. 68, 2345–2360 (2017).

Irisarri, I. et al. Unexpected cryptic species among streptophyte algae most distant to land plants. Proc. R. Soc. B 288, 20212168 (2021).

Vaughn, K. C., Campbell, E. O., Hasegawa, J., Owen, H. A. & Renzaglia, K. S. The pyrenoid is the site of ribulose 1,5-bisphosphate carboxylase/oxygenase accumulation in the hornwort (Bryophyta: Anthocerotae) chloroplast. Protoplasma 156, 117–129 (1990).

Smith, E. & Griffiths, H. A pyrenoid-based carbon-concentrating mechanism is present in terrestrial bryophytes of the class Anthocerotae. Planta 200, 203–212 (1996).

Li, F.-W., Villarreal Aguilar, J. C. & Szövényi, P. Hornworts: an overlooked window into carbon-concentrating mechanisms. Trends Plant Sci. 22, 275–277 (2017).

Vaughn, K. C. et al. The anthocerote chloroplast: a review. N. Phytol. 120, 169–190 (1992).

Li, F.-W. et al. Anthoceros genomes illuminate the origin of land plants and the unique biology of hornworts. Nat. Plants 6, 259–272 (2020).

Szövényi, P. et al. Establishment of Anthoceros agrestis as a model species for studying the biology of hornworts. BMC Plant Biol. 15, 98 (2015).

Lafferty, D. J. et al. Biolistics-mediated transformation of hornworts and its application to study pyrenoid protein localization. J. Exp. Bot. 75, 4760–4771 (2024). erae243.

Schafran, P. et al. Pan-phylum genomes of hornworts reveal conserved autosomes but dynamic accessory and sex chromosomes. Nat. Plants (in the press).

Barrett, J., Girr, P. & Mackinder, L. C. M. Pyrenoids: CO2-fixing phase separated liquid organelles. Biochim. Biophys. Acta Mol. Cell. Res. 1868, 118949 (2021).

Oh, Z. G. et al. A linker protein from a red-type pyrenoid phase separates with Rubisco via oligomerizing sticker motifs. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 120, e2304833120 (2023).

Burr, F. A. Phylogenetic transitions in the chloroplasts of the Anthocerotales. I. The number and ultrastructure of the mature plastids. Am. J. Bot. 57, 97–110 (1970).

Mackinder, L. C. M. et al. A spatial interactome reveals the protein organization of the algal CO2-concentrating mechanism. Cell 171, 133–147.e14 (2017).

Mukherjee, A. et al. Thylakoid localized bestrophin-like proteins are essential for the CO2 concentrating mechanism of Chlamydomonas reinhardtii. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 116, 16915–16920 (2019).

Ignatova, L., Rudenko, N., Zhurikova, E., Borisova-Mubarakshina, M. & Ivanov, B. Carbonic anhydrases in photosynthesizing cells of C3 higher plants. Metabolites 9, 73 (2019).

Badger, M. R. & Price, G. D. The role of carbonic anhydrase in photosynthesis. Annu. Rev. Plant Physiol. Plant Mol. Biol. 45, 369–392 (1994).

Almagro Armenteros, J. J. et al. Detecting sequence signals in targeting peptides using deep learning. Life Sci. Alliance 2, e201900429 (2019).

Jethva, J. et al. Realisation of a key step in the evolution of C4 photosynthesis in rice by genome editing. Preprint at bioRxiv https://doi.org/10.1101/2024.05.21.595093 (2024).

Smith, E. C. & Griffiths, H. The role of carbonic anhydrase in photosynthesis and the activity of the carbon-concentrating-mechanism in bryophytes of the class Anthocerotae. N. Phytol. 145, 29–37 (2000).

Sinetova, M. A., Kupriyanova, E. V., Markelova, A. G., Allakhverdiev, S. I. & Pronina, N. A. Identification and functional role of the carbonic anhydrase Cah3 in thylakoid membranes of pyrenoid of Chlamydomonas reinhardtii. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1817, 1248–1255 (2012).

Mitra, M. et al. The carbonic anhydrase gene families of Chlamydomonas reinhardtii. Can. J. Bot. 83, 780–795 (2005).

Terentyev, V. V. & Shukshina, A. K. CAH3 from Chlamydomonas reinhardtii: unique carbonic anhydrase of the thylakoid lumen. Cells 13, 109 (2024).

Wang, Y. & Spalding, M. H. LCIB in the Chlamydomonas CO2-concentrating mechanism. Photosynth. Res. 121, 185–192 (2014).

Jin, S. et al. Structural insights into the LCIB protein family reveals a new group of β-carbonic anhydrases. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 113, 14716–14721 (2016).

Yamano, T., Toyokawa, C., Shimamura, D., Matsuoka, T. & Fukuzawa, H. CO2-dependent migration and relocation of LCIB, a pyrenoid-peripheral protein in Chlamydomonas reinhardtii. Plant Physiol. 188, 1081–1094 (2021).

Chou, M.-L. et al. Tic40, a membrane-anchored co-chaperone homolog in the chloroplast protein translocon. EMBO J. 22, 2970–2980 (2003).

Barrett, J. et al. A promiscuous mechanism to phase separate eukaryotic carbon fixation in the green lineage. Preprint bioRxiv https://doi.org/10.1101/2024.04.09.588658 (2024).

Moromizato, R. et al. Pyrenoid proteomics reveals independent evolution of the CO2-concentrating organelle in chlorarachniophytes. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 121, e2318542121 (2024).

Aigner, H. et al. Plant RuBisCo assembly in E. coli with five chloroplast chaperones including BSD2. Science 358, 1272–1278 (2017).

Feiz, L. et al. Ribulose-1,5-bis-phosphate carboxylase/oxygenase accumulation factor1 is required for holoenzyme assembly in maize. Plant Cell 24, 3435–3446 (2012).

Saschenbrecker, S. et al. Structure and function of RbcX, an assembly chaperone for hexadecameric Rubisco. Cell 129, 1189–1200 (2007).

Wang, L. et al. A chloroplast protein atlas reveals punctate structures and spatial organization of biosynthetic pathways. Cell 186, 3499–3518.e14 (2023).

Badger, M. R. et al. The diversity and coevolution of Rubisco, plastids, pyrenoids, and chloroplast-based CO2-concentrating mechanisms in algae. Can. J. Bot. 76, 1052–1071 (1998).

Kevekordes, K. et al. Inorganic carbon acquisition by eight species of Caulerpa (Caulerpaceae, Chlorophyta). Phycologia 45, 442–449 (2006).

Gee, C. W. & Niyogi, K. K. The carbonic anhydrase CAH1 is an essential component of the carbon-concentrating mechanism in Nannochloropsis oceanica. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 114, 4537–4542 (2017).

Steensma, A. K., Shachar-Hill, Y. & Walker, B. J. The carbon-concentrating mechanism of the extremophilic red microalga Cyanidioschyzon merolae. Photosynth. Res. 158, 203 (2023).

Villarreal, J. C. & Renner, S. S. Hornwort pyrenoids, carbon-concentrating structures, evolved and were lost at least five times during the last 100 million years. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 109, 18873–18878 (2012).

Hanson, D., John Andrews, T. & Badger, M. R. Variability of the pyrenoid-based CO2 concentrating mechanism in hornworts (Anthocerotophyta). Funct. Plant Biol. 29, 407–416 (2002).

Atkinson, N., Mao, Y., Chan, K. X. & McCormick, A. J. Condensation of Rubisco into a proto-pyrenoid in higher plant chloroplasts. Nat. Commun. 11, 6303 (2020).

Atkinson, N., Stringer, R., Mitchell, S. R., Seung, D. & McCormick, A. J. SAGA1 and SAGA2 promote starch formation around proto-pyrenoids in Arabidopsis chloroplasts. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 121, e2311013121 (2024).

Kaste, J. A. M., Walker, B. J. & Shachar-Hill, Y. Reaction–diffusion modeling provides insights into biophysical carbon concentrating mechanisms in land plants. Plant Physiol. 196, 1374–1390 (2024).

Gunadi, A., Li, F.-W. & Van Eck, J. Accelerating gametophytic growth in the model hornwort Anthoceros agrestis. Appl. Plant Sci. 10, e11460 (2022).

Villarreal, J. C., Duckett, J. G. & Pressel, S. Morphology, ultrastructure and phylogenetic affinities of the single-island endemic Anthoceros cristatus Steph. (Ascension Island). J. Bryol. 39, 226–234 (2017).

Sauret-Gueto, S. et al. Systematic tools for reprogramming plant gene expression in a simple model, Marchantia polymorpha. ACS Synth. Biol. 9, 864–882 (2020).

R Core Team. R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing. (R Foundation for Statistical Computing, 2023).

Schindelin, J. et al. Fiji: an open-source platform for biological-image analysis. Nat. Methods 9, 676–682 (2012).

Emms, D. M. & Kelly, S. OrthoFinder: phylogenetic orthology inference for comparative genomics. Genome Biol. 20, 238 (2019).

Minh, B. Q. et al. IQ-TREE 2: new models and efficient methods for phylogenetic inference in the genomic era. Mol. Biol. Evol. 37, 1530–1534 (2020).

Newman, A. M. & Cooper, J. B. XSTREAM: a practical algorithm for identification and architecture modeling of tandem repeats in protein sequences. BMC Bioinform. 8, 382 (2007).

Gasteiger, E. et al. ExPASy: the proteomics server for in-depth protein knowledge and analysis. Nucleic Acids Res. 31, 3784–3788 (2003).

Romero, P. et al. Sequence complexity of disordered protein. Proteins 42, 38–48 (2001).

Wiśniewski, J. R., Zougman, A., Nagaraj, N. & Mann, M. Universal sample preparation method for proteome analysis. Nat. Methods 6, 359–362 (2009).

Monroe, M. E., Shaw, J. L., Daly, D. S., Adkins, J. N. & Smith, R. D. MASIC: a software program for fast quantitation and flexible visualization of chromatographic profiles from detected LC-MS(/MS) features. Comput. Biol. Chem. 32, 215–217 (2008).

Polpitiya, A. D. et al. DAnTE: a statistical tool for quantitative analysis of -omics data. Bioinformatics 24, 1556–1558 (2008).

Zhang, X. et al. Proteome-wide identification of ubiquitin interactions using UbIA-MS. Nat. Protoc. 13, 530–550 (2018).

Wickham, H. ggplot2: Elegant Graphics for Data Analysis. (Springer-Verlag, 2016).

Chen, C. et al. TBtools: an integrative toolkit developed for interactive analyses of big biological data. Mol. Plant 13, 1194–1202 (2020).

Acknowledgements

This work is supported by National Science Foundation grant no. MCB-2213841 to F.-W.L. and grant no. MCB-2213840 to L.H.G., an Environmental Molecular Sciences Laboratory User Grant to F.-W.L., a Triad Foundation Grant to F.-W.L. and a Schmittau-Novak Graduate Student Grant to T.A.R. We thank A. Skirycz, K. Eshenour, A. Hotto and D. Stern of Boyce Thompson Institute for providing access to tools and reagents to establish preliminary lysis and co-IP experiments. We thank R. Key at the University of Florida for the illustration in Fig. 6. We also thank C. Nicora and N. Tolic from the Environmental Molecular Sciences Laboratory at the Pacific Northwest National Laboratory for technical assistance with mass spectrometry processing, M. Srivastava at the Boyce Thompson Institute Plant Cell Imaging Center for technical assistance with confocal imaging using the Leica TCS SP5 Laser Scanning Confocal Microscope and A. Roeder at Cornell University for providing access to the Zeiss LSM710 and Leica Stellaris 5 confocal microscopes. Finally, we thank the York Physics of Pyrenoids research community for feedback and Li and Gunn lab members for discussions.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

T.A.R., L.H.G. and F.-W.L. conceived the project. T.A.R. made the gene constructs and carried out the confocal imaging. T.A.R., D.L. and X.X. performed the hornwort transformation. Z.G.O. designed the Rubisco antibody and optimized the lysis of hornwort thallus. T.A.R. and Z.G.O. performed the co-IP experiments. J.C.A.V. performed TEM. T.A.R., Z.G.O., L.H.G. and F.-W.L. analysed the data. T.A.R. and F.-W.L. wrote the manuscript with contributions and comments from all authors. L.H.G. and F.-W.L. secured the funding and supervised the project.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Plants thanks Nicky Atkinson, Manon Demulder and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Supplementary Information

Supplementary Figs. 1–14 and Tables 1 and 2.

Supplementary Video 1

Confocal Z-stack series of A. agrestis stably expressing RCA–mVenus (green). Pyrenoids that do not have obvious connections to one another are indicated by arrows. Chlorophyll autofluorescence is shown in blue.

Supplementary Video 2

Confocal Z-stack series of A. agrestis stably expressing RCA–mVenus (green). Pyrenoids that do not have obvious connections to one another are indicated by arrows. Chlorophyll autofluorescence is shown in blue.

Supplementary Video 3

Time-lapse video of A. agrestis stably expressing RCA–mVenus during cell division over 75 minutes. Chlorophyll autofluorescence is shown in blue and RCA–mVenus fluorescence in green.

Supplementary Video 4

Confocal Z-stack series of A. agrestis transiently expressing RCA–mScarlet (magenta) and CAH3–mVenus (green).

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Robison, T.A., Oh, Z.G., Lafferty, D. et al. Hornworts reveal a spatial model for pyrenoid-based CO2-concentrating mechanisms in land plants. Nat. Plants 11, 63–73 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41477-024-01871-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

Issue date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41477-024-01871-0