Abstract.

In the Ametista do Sul area, Rio Grande do Sul, Brazil, amethyst-bearing geodes are hosted by a ~40- to 50-m-thick subhorizontal high-Ti basaltic lava flow of the Lower Cretaceous Paraná Continental Flood Basalt Province. The typically spherical cap-shaped, sometimes vertically elongated geodes display an outer rim of celadonite followed inwards by agate and colorless and finally amethystine quartz. Calcite formed throughout the whole crystallization sequence, but most commonly as very late euhedral crystals, sometimes with gypsum, in the central cavity. Fluid inclusions in colorless quartz and amethyst are predominantly monophase and contain an aqueous liquid. Two-phase liquid–vapor inclusions are rare. Some with a consistent degree of fill homogenize into the liquid between 95 and 98 °C. Ice-melting temperatures in the absence of a vapor phase between –4 and +4 °C indicate low salinities. Chondrite-normalized REE patterns of calcites are highly variable and show generally no systematic correlation with the paragenetic sequence. The oxygen isotope composition of calcites is very homogeneous (δ18OVSMOW=24.9±1.1‰, n=34) indicating crystallization temperatures of less than 100 °C. Carbon isotope values of calcites show a considerable variation ranging from –18.7 to –2.9‰ (VPDB). The 87Sr/86Sr ratio of calcites varies between 0.706 and 0.708 and is more radiogenic than that of the host basalt (~0.705). The most likely source of silica, calcium, carbon, and minor elements in the infill of the geodes is the highly reactive interstitial glass of the host basalts leached by gas-poor aqueous solutions of meteoric origin ascending from the locally artesian Botucatú aquifer system in the footwall of the volcanic sequence. The genesis of amethyst geodes in basalts at Ametista do Sul, Brazil, is thus considered as a two-stage process with an early magmatic protogeode formation and a late, low temperature infill of the cavity.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Amethyst is the violet variety of α-quartz. The role of trace amounts of iron and radiation in the formation of its color is broadly established, although details about the responsible color centers are still unknown (e.g., Rossman 1994). Amethyst is found in a variety of geological environments such as alpine clefts, epithermal veins, miaroles in granitic rocks, or geodes in basaltic lavas. Brazil and Uruguay are the world leaders in the production of gem quality amethyst from geodes in basaltic rocks of the Paraná Continental Flood Basalt Province. In Brazil, the deposits of economic interest are found in the Ametista do Sul region, south of Iraí, in the northern tip of the State of Rio Grande do Sul (Fig. 1a). In 1993, about 100 to 200 tons (t) of geodes per month and 20 to 30 t of amethyst crystals for cutting per month were produced in this region (Corrêa et al. 1994). The Uruguayan amethyst deposits are located at Artigas in the northwestern part of the state near the border to Brazil (Fig. 1a).

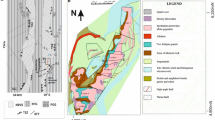

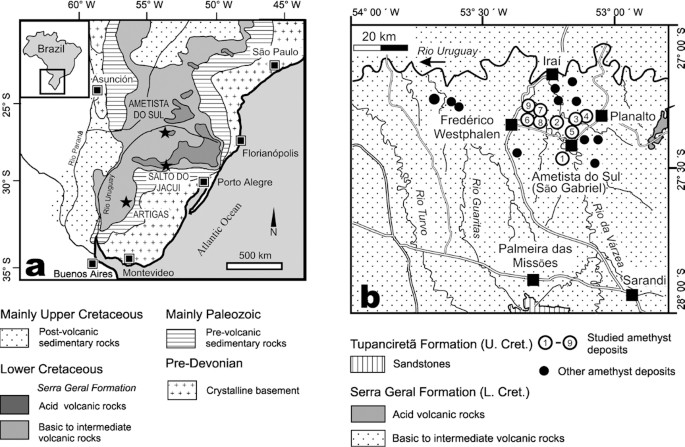

a Geological sketch map of the southern Paraná basin with the location of the amethyst mining areas of Ametista do Sul (Brazil) and Artigas (Uruguay), as well as the agate mining area of Salto do Jacuí (Brazil). b Detailed map of the Ametista do Sul area, Rio Grande do Sul, Brazil, with location of investigated amethyst mines ("garimpos"). 1 Mioto; 2 Célio; 3 Narciso; 4 Testa; 5 Salles; 6 Trock; 7 Zanon; 8 Bortoluzzi; 9 Simonetti

The genesis of amethyst (± agate)-bearing geodes hosted by volcanic rocks is still debated. According to Leinz (1949) and Corrêa et al. (1994), exsolution of volatiles from the basaltic magma was responsible for the formation of cavities ("protogeodes") that have been filled later by fluids of magmatic or undefined origin. This model was then accepted, e.g., by Meunier et al. (1988), Scopel et al. (1998), and Juchem et al. (1999). In contrast, Bossi and Caggiano (1974), Borget (1985), and Montaña and Bossi (1993) suggested that geode formation in Uruguay is related to fusion or dissolution of sandstone xenoliths from the underlying Rivera and Tacuarembo Formation. Similarly, Wang and Merino (1990, 1995) and Merino et al. (1992, 1995) developed a model for the formation of geodes and their infill from lumps of silica formed by reaction of hot basalt with surface water or by liquid immiscibility.

There is also considerable debate concerning the temperatures of amethyst crystallization. Thomas and Blankenburg (1981) presented fluid-inclusion data of quartz incrustations from geodes of Rio Grande do Sul, Brazil, indicating minimum formation temperatures of 370 to 420 °C, whereas fluid inclusion data on Brazilian amethysts by Juchem et al. (1999) suggest temperatures below 50 °C. Stable oxygen isotope data from amethyst- and agate-bearing geodes hosted in the Paraná-Etendeka volcanics (Fallick et al. 1987; Harris 1989; Juchem et al. 1999) and in Devonian and Tertiary volcanics of Scotland (Fallick et al. 1985, 1987) also indicate rather low formation temperatures (<150 °C). Amethyst in granite-hosted veins of the Thunder Bay amethyst mine, Ontario, Canada, were formed similarly in a temperature range of 40–90 °C (McArthur et al. 1993). In contrast, amethysts from epithermal polymetallic or Au–Ag vein deposits mainly hosted by volcanic rocks, such as Creede (Colorado, USA) or Gyöngyösoroszi (Hungary), have formation temperatures ranging from 150 to 250 °C based of fluid-inclusion studies (Balitsky 1978; Robinson and Norman 1984; Gatter 1987). Even higher fluid-inclusion homogenization temperatures (280–400 °C) were reported from amethyst in miaroles within granites of the Eonyang deposit, South Korea (Yang et al. 2001). Such high temperatures are also applied in hydrothermal amethyst synthesis in the laboratory (Balitsky 1978). There is also no consensus on the origin of amethyst-forming fluids (magmatic to meteoric) and the mechanism of geode filling and amethyst ± agate precipitation, such as boiling, fluid mixing, cooling, or crystallization from gel (e.g., Landmesser 1984; Harris 1989; Merino et al. 1992; McArthur et al. 1993).

In order to better constrain the formation of amethyst-bearing geodes of the Ametista do Sul region, Rio Grande do Sul, Brazil, we conducted a combined fluid inclusion, REE, stable (C,O), and radiogenic (Sr) isotope study on amethyst, colorless quartz, calcite, and gypsum from geodes and the associated rocks (host basalts, sandstones). For comparison, we included some amethyst-free, calcite-bearing agate geodes from Salto do Jacuí, Rio Grande do Sul, Brazil (Fig. 1a), in our study. This area is, together with the adjacent Soledade–Lajeado area, the major producer of agate from geodes in the Paraná basalts in Brazil.

Regional geology

The Paraná Continental Flood Basalt Province of South America covers an area of 1.2 million km2 in Brazil, Uruguay, Paraguay, and Argentina and reaches a maximum thickness of approximately 1.7 km (Piccirillo and Melfi 1988). The eruption of the Paraná volcanic rocks is closely associated with the opening of the South Atlantic Ocean and the arrival of the Tristan mantle plume. More than 800,000 km3 of mainly tholeiitic basaltic to andesitic–basaltic (90 vol%) and subordinate andesitic (7 vol%) as well as rhyodacitic to rhyolitic (3 vol%) lavas were extruded during the Early Cretaceous period between 138 and 127 Ma (Renne et al. 1992; Turner et al. 1994; Stewart et al. 1996). The volcanic rock sequence, also known as Serra Geral Formation in Brazil and Arapey Formation in Uruguay, can be subdivided geochemically into a high-Ti or high-Ti/Y group (basalts of Pitanga, Paranápanema and Urubici type and rhyolites of the Chapeco type) and a low-Ti or low-Ti/Y group (basalts of Gramado and Esmeralda type and rhyolites of Palmas type; Peate et al. 1992). The various magma types erupted largely diachronously (Stewart et al. 1996) with older high-Ti volcanics mostly in the northwest and younger low-Ti lavas in the southeast portion of the province. The volcanic rocks are underlain by a several-kilometer-thick sequence of mainly sedimentary rocks ranging from Devonian to Early Cretaceous as part of the Paraná Basin infill (Piccirillo and Melfi 1988). Red arkosic eolian sandstones of the Jurassic to Early Cretaceous Botucatú Formation are found in the immediate footwall of the flood basalt sequence as well as intercalated layers in the volcanics with a thickness of up to 160 m.

Local geology

We studied samples from nine amethyst underground mines or "garimpos" (Salles, Célio, Testa, Trock, Narciso, Mioto, Zanon, Simonetti, Bortoluzzi) in the area of Ametista do Sul (former village São Gabriel), near Iraí in the northern part of Rio Grande do Sul, Brazil (Fig. 1b). The local geology of the Ametista do Sul region is described in detail by Szubert et al. (1978), Cassedanne (1988), and Corrêa et al. (1994). Up to nine individual subhorizontal basaltic lava flows were mapped in the area. The deposits of the amethyst-bearing geodes are located in the fifth flow, named São Gabriel Flow by Corrêa et al. (1994), in a rather well-defined horizon (Fig. 2a) at 400 to 440 m above sea level. This flow can be subdivided into the following units from the top to the base:

-

1.

A 5- to 10-m-thick strongly weathered, vesicular basalt horizon (vesicle size up to 3 cm in diameter) with breccias including angular Botucatú sandstone blocks at the top.

-

2.

A 0.3- to 1.5-m-thick transitional zone of highly (mainly subhorizontally) fractured aphanitic basalt.

-

3.

A 20- to 30-m-thick massive basalt called "basalto portador" by the local miners with the geode-bearing horizon (Fig. 2a). This unit can be further subdivided from top to bottom into a 2- to 4-m-thick layer hosting the amethyst geodes, a 10- to 25-m-thick layer of massive basalt with rare vertical fractures, and a 3- to 5-m-thick basal horizon with frequent horizontal fractures.

a Photograph of entrances (arrows) to underground amethyst mines near Ametista do Sul, Rio Grande do Sul, Brazil. Note their alignment at a specific level within the subhorizontal basaltic lava flow. b Typical cap-shaped amethyst-bearing geode with dimpled base (10 cm diameter) in massive basalt. c Vertically elongated amethyst geode (1.5 m high) with calcite crystals

The Salto do Jacuí area in central Rio Grande do Sul is located some 50 km further south of Ametista do Sul. Agate-bearing geodes are mined along the Rio Jacuí and Rio Ivaí mainly from a 5- to 8-m-thick vesicular basalt flow (also named "basalto portador") within a complex association of intercalated basaltic and (rhyo-)dacitic lava flows with frequent Botucatú sandstone lenses and dikes outcropping between 200 and 400 m above sea level. This bimodal sequence was deposited on a sequence of massive basalt flows of ~120 m total thickness and Botucatú sandstones. The geode-bearing basalt is sandwiched between an underlying vesicular glass-rich dacite (2 to 3 m) and a vesicular rhyodacite ("cupim"; 5–7 m) that both may occasionally contain agate geodes. The geodes contain banded chalcedony (agate), often followed by a central zone of clear macrocrystalline euhedral quartz. Amethyst and calcite is, in contrast to the Ametista do Sul area, very rare. Our samples come from the mines Angico (53°16′7.0′′W, 29°6′21.0′′S) and Zubi (53°15′31.5′′W, 29°6′11.9′′S).

Petrography of amethyst-bearing geodes

The size of amethyst geodes ranges from a few centimeters up to 6 m in the largest dimension. The geodes have predominantly a spherical cap or plume head shape (Fig. 2b), but can also be elongated vertically like a chimney (Fig. 2c). The base of the geode is generally dimpled, upward convex (Fig. 2b). The geodes are separated from the host basalt by a dark green rim of fine-grained celadonite, which facilitates their extraction during mining. The green botryoidal celadonite rim is followed inward by a zone of concentrically banded agate or chalcedony. Rarely agate stalactites occur in the cavities. The thickness of the agate and celadonite rim is very variable from a few millimeters to some centimeters. We also observed brecciated textures with fragments of basalt with celadonite detached from the geode wall and cemented by agate, and ductile deformation zones within the agate ("infiltration or escape tubes"; Landmesser 1984). Microcrystalline agate is followed by a zone of euhedral terminating quartz crystals. In rare cases, two or three cycles of chalcedony–quartz (± celadonite) deposition are recorded within a single geode. The violet color of quartz typically increases towards the central cavity that sometimes contains euhedral clear, whitish and yellowish calcite crystals, or more rarely clear gypsum. However, calcite formed throughout the paragenetic sequence (Fig. 3). The earliest calcite generation (Cc-1) is intergrown with celadonite and rare pyrite at the rim of the geode. But, calcite can be completely embedded in agate (Cc-2) and is more often found in the macrocrystalline quartz–amethyst zone (Cc-3). Microscopic studies revealed the presence of tiny calcite crystal, as well as lepidocrocite and goethite needles in amethyst (Fig. 4d). The youngest generation of euhedral calcite in the cavities (Cc-4) displays a variety of crystal habits ranging from flat rhombohedra to elongated scalenohedra and long prismatic crystals. Very rarely barite crystals (Juchem 1999), or pseudomorphs of quartz after anhydrite (Lieber 1985), are found in the central cavity.

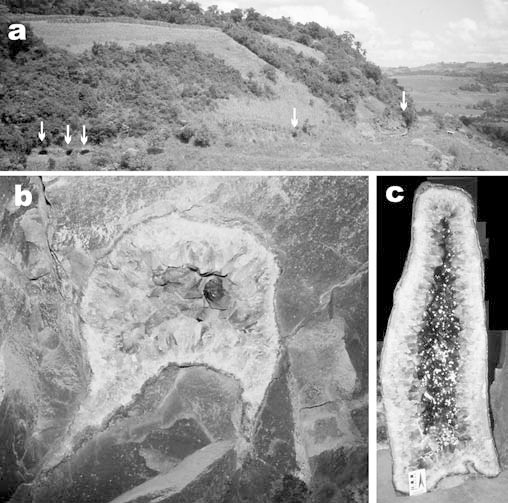

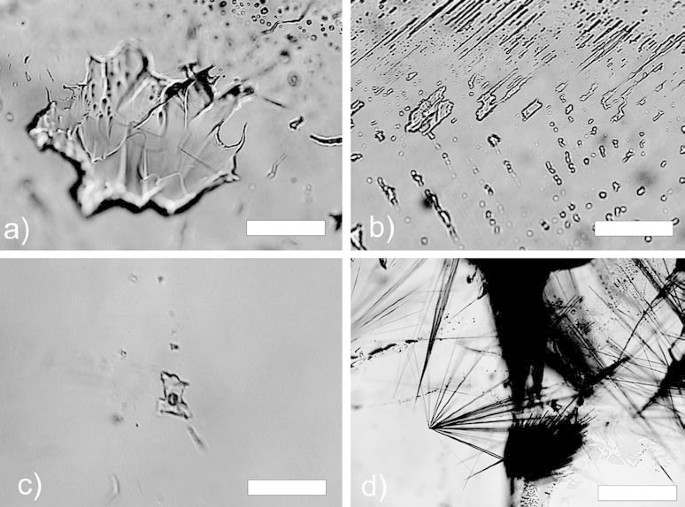

Photomicrographs of fluid and solid inclusions in amethyst. a Primary monophase aqueous fluid inclusion (sample no. 15343, Zanon). b Tubular pseudosecondary monophase aqueous fluid inclusions (sample no. 15284, Célio). c Liquid–vapor inclusion (sample no. 15310, Testa). d Radiating goethite needles (sample no. 15284, Célio). Scale bar in all micrographs is 10 µm

Analytical techniques

Fluid and solid inclusions were inspected in 0.2- to 0.5-mm-thick doubly polished plates cut parallel to the c axis of the crystals. Microthermometric measurements were performed on a Linkham THMS-600 heating–freezing stage with TMS and TP94 controllers calibrated with synthetic fluid inclusions.

The chemical composition of whole rocks was determined on Li tetraborate glass discs by routine X-ray fluorescence analysis using a fully automated Siemens SRS 303 equipment with wave-length dispersive spectrometers. Rare earth elements (REE) contents were analyzed using ICP-MS by X-Ral (Canada) and at GeoForschungsZentrum Potsdam, Germany.

For oxygen and carbon isotope analysis, CO2 was extracted from calcites by reaction with anhydrous phosphoric acid at 25 °C in sealed vessels (McCrea 1950). The isotope analyses of CO2 were performed on a Finnigan MAT 251 double inlet mass spectrometer at the Technische Universität München. Isotope ratios are expressed as delta values relative to VPDB for carbon and VSMOW for oxygen. The analytical precision is estimated from repeated measurements of international standards (NBS-18, NBS-19) at 0.1 to 0.2‰ for both isotope ratios.

Sulfur isotope analyses were performed by Dr. A. Voropayev (Hydroisotope Co., Schweitenkirchen). Sulfur dioxide was produced from sulfates by reaction with V2O5 and SiO2 at 950 °C (Ueda and Krouse 1987). To facilitate the conversion of SO3 to SO2, partial pressure of oxygen was minimized by using pre-heated Cu placed in a quartz-tube reactor a few centimeters from the samples at 700 °C. The SO2 was purified using cold traps with mixtures of liquid nitrogen and n-pentane and dry alcohol slush. The sulfur isotope composition of SO2 was measured using a Finnigan 250 mass spectrometer with a precision in the δ34SCDT value of ±1.0‰. Oxygen was liberated from sulfates by reaction with ClF3 and converted to CO2 over hot graphite. A pre-fluorination step was introduced before analysis to remove hydration water in gypsum. The analytical precision of the δ18OVSMOW value of sulfates is ±0.2‰.

The isotopic composition of Sr, as well as Rb and Sr contents, were determined by the isotopic dilution method using a 85Rb + 84Sr mixed spike. The spike aliquots were added to solid samples, before acid dissolution. For isotope analysis 20–30 mg of weighted silicate samples were dissolved in 3 ml of HF + HNO3 mixture at 100 °C overnight, excluding carbonate samples, which were dissolved in cold 2 N HCl. After complete dissolution, the sample solution was evaporated under an IR lamp and dissolved in 3 ml of 12 N HCl, then again dried and dissolved in 1.5 ml of 2.3 N HCl for ion exchange separation of Rb and Sr. Isotope analyses were performed on a MI-1201T mass spectrometer. The precision of Sr isotopic composition determination is about 0.01%; that of the Rb/Sr ratio is about 1% (all errors correspond to a 95% confidence level). The blank level for Rb is 0.2 ng, for Sr it is 0.8 ng. The average 87Sr/86Sr ratio for SRM-987 was 0.71024±5 and for 84Sr/86Sr it was 0.05648±5 (n=4).

Fluid inclusions

Amethyst and colorless quartz contain primary, pseudosecondary and secondary fluid inclusions (Fig. 4). Sometimes small anhedral calcite aggregates (5–20 µm) or corroded calcite rhombohedra or radiating goethite needles were found as solid inclusions in amethyst. In colorless quartz and amethyst, primary fluid inclusions found aligned parallel to the rhombohedral faces of the host crystal have irregular shapes (Fig. 4a), but are scarce. Pseudosecondary fluid inclusions are more abundant. They occur along healed fractures starting from growth planes or form small two-dimensional clusters within the crystal. These inclusions are rounded or cylindrical and very rarely show negative crystal shapes. Secondary fluid inclusions along former fractures are the most frequent type of inclusions. They exhibit a variety of shapes and very often show "necking down" phenomena (Fig. 4b). Many fractures are, however, not healed. They frequently, but not exclusively, occur in areas of Brazil-law twinning indicating that fracturing was not related to external tectonic deformation or thermal shock, but rather to internal stress related to growth twinning and/or variable trace element incorporation (Audétat and Günter 1999).

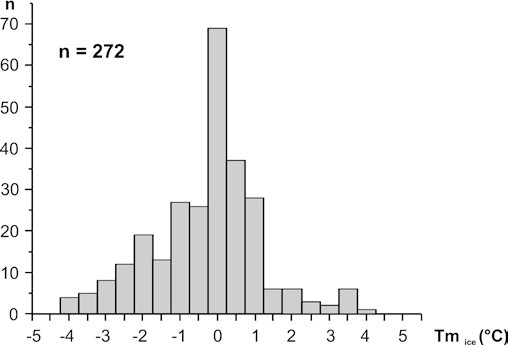

At room temperature, almost all inclusions regardless of their relative ages are monophase and contain a colorless liquid. Various attempts to generate a vapor bubble in these inclusions by rapid freezing to –180 °C or prolonged undercooling at about –25 °C in a refrigerator were unsuccessful. Thus homogenization temperature measurements for these inclusions could not be obtained. Freezing experiments on monophase inclusions show rapid solidification between –28 and –48 °C. Upon slow heating, apparent first melting (Tfm) or recrystallization was observed between –20 and –42 °C. Final melting of a solid phase (Tmice) occurred in the absence of a vapor bubble between –4.5 and +4.5 °C with a maximum of around 0 °C (Fig. 5). Crushing experiments did not reveal the presence of any gases under pressure, such as methane or carbon dioxide. We interpret the microthermometric results to indicate the presence of an aqueous liquid with a rather low salt content in these monophase inclusions. As the first and last melting of ice in the absence of a vapor phase in a two-component water–salt system does not only depend on composition of the salt (Tfm) and salt content (Tmice), respectively, but also on the internal pressure of the inclusion (e.g., Goldstein and Reynolds 1994), the salinity of these inclusions cannot be quantified. Thus, calculated salt contents of up to 10 wt% NaCl equivalent for monophase inclusions, as reported by Juchem et al. (1994), are not considered reliable. We note that significant depression of first and last melting temperatures could be related to an internal pressure increase due to expansion of the aqueous liquid during freezing. On the other hand, metastable stretching of the monophase aqueous liquid during cooling may also create negative internal pressures leading to ice-melting temperatures above 0 °C (Roedder 1967). Monophase aqueous liquid inclusions are indicative of low temperatures of formation, i.e., less than ~50–80 °C (Arnold 1986; Goldstein and Reynolds 1994).

Two-phase liquid–vapor inclusions are very rarely found in some pseudosecondary trails in colorless quartz. They are mostly associated with monophase liquid inclusions and display variable phase volume ratios and typical necking down phenomena. Some liquid–vapor inclusions have consistent phase volume ratios (sample 15278, Fig. 4c). They have a high degree of fill [VLIQ/(VLIQ+VVAP)>0.9] and homogenize into the liquid phase between 95 and 98 °C. Despite their relatively consistent phase volume ratios, it cannot be excluded that even these inclusions formed by necking in the presence of a vapor phase. In that case, homogenization temperatures have to be interpreted as maximum trapping temperatures. First melting is recorded at –29 °C and final ice melting temperatures in two-phase inclusions scatter between –0.9 and –0.8 °C similar to the majority of monophase liquid inclusions, suggesting that they are of the same lineage. Calculated salinities for the two-phase inclusions are less than 2 wt% NaCl equivalent (Bodnar et al. 1985).

Our microthermometric results are consistent with the data of Juchem et al. (1994) and Juchem (1999), suggesting that temperatures during and after amethyst crystallization never exceeded 100 °C, but were probably even below 50–80 °C. In contrast to interpretations by Juchem et al. (1994), salt contents of mineralizing fluids were not higher than 2 wt% NaCl equivalent.

Composition of host basalts

The chemical composition of mafic volcanic rocks hosting the geodes in the Ametista do Sul area, as well as those primarily hosting agates in the Salto do Jacuí region, are presented in Table 1 . The hypocrystalline, aphyric to subaphyric host rocks of amethyst-bearing geodes consist mainly of plagioclase (labradorite to andesine), augitic clinopyroxene, rare and often altered olivine, as well as apatite, magnetite, and a partly glassy, partly crystallized silicic mesostasis that exhibits local argillic alteration (Meunier et al. 1988). The immediate host rocks are highly porous with irregular cavities with diameters of less than 1 mm, which might be related to leaching of the glass phase. Some of these small cavities are filled with celadonite. The volcanic rocks can be classified as tholeiitic basalts showing a clear within-plate signature (Zr/Y >6) typical of the volcanic rocks of the Paraná Continental Flood Basalt Province (e.g., Piccirillo et al. 1988). The high TiO2 content (>3.4 wt%), high Ti/Y ratios (>310), low Sr content (<500 ppm), and low initial 87Sr/86Sr ratios (see below) are distinctive for the lavas of the Pitanga Group (Peate et al. 1992; Scopel et al. 1998) and thus indicate a position within the basal part of the volcanic succession in that area.

In contrast, the host sequence for agate-bearing geodes in the Salto do Jacuí region are intercalated vesicular dacites to rhyodacites and basalts. Our two samples (Table 1 ) have dacitic to rhyodacitic composition, low Ti (<1.0 wt%), as well as Zr content (~250 ppm) and high initial 87Sr/86Sr ratios (see below), suggesting that they belong to the silicic Palmas Group (Piccirillo et al. 1988).

Rare earth element distribution

The chondrite normalized rare earth element patterns of basalts hosting the amethyst geodes (Fig. 6, Table 1 ) display a LREE enrichment (~100 times chondritic for La) with no Eu anomalies. The REE distribution patterns of the Botucatú arkosic sandstones show decreasing LREE contents and a rather flat pattern of HREE as well as marked negative Eu and Ce anomalies. The negative Eu anomaly may have been inherited from a granitic to gneissic source terrain (e.g., McLennan 1989). The negative Ce anomaly is typical of highly oxidized sediments. A rhyodacite sample from Salto do Jacuí overlying the host basalts ("cupim") displays a pronounced negative Eu anomaly (Fig. 6), suggesting the involvement of significant feldspar fractionation in the genesis of these acid volcanic rocks.

The REE patterns of calcites in amethyst geodes (Fig. 7) are extremely variable, even within individual mines. There is also no systematic correlation of REE content or pattern with paragenetic sequence. Most calcites display a continuous decrease of chondrite normalized REE content from light to heavy REE with either a marked negative Eu and/or slight Ce anomaly, or none of both. Other calcites have flat patterns or increased HREE contents. This pronounced variability of REE patterns of calcites in geodes contrasts with the relatively consistent distribution pattern reported by Götze et al. (2001) for calcites from various agate deposits that was, however, based on a much smaller data set and only one sample from Rio Grande do Sul.

The REE characteristics of calcites indicate significant variability in either fluid chemistry, fluid–rock interaction, or physico-chemical conditions during calcite precipitation, or any combination of these (e.g., Möller et al. 1984; Bau 1991; Hecht et al. 1999). Variations in mineral growth and solution flow rates may additionally affect the total REE content (Möller et al. 1991).

Considering the relatively oxidizing conditions (goethite and celadonite) and the relatively low temperatures during geode filling, the frequently observed negative Eu anomalies in calcite are most probably inherited from one or more source rock(s) by fluid–rock interaction prior to calcite precipitation (e.g., Bau 1991). However, whole-rock analyses of host basalts do not exhibit such Eu anomalies. Therefore, Eu anomalies in calcite are either acquired through significant fluid–rock interaction with Botucatú sandstone, or, alternatively, with a highly fractionated interstitial glass phase in the hypocrystalline basalts. Although such glassy material could not be separated from the basalts for REE analysis, it has to be considered as a potential source for such Eu anomalies. Note that the rhyodacite from Salto do Jacuí exhibits a negative Eu anomaly (Fig. 6). We also want to emphasize that no positive Eu anomaly has been encountered in our samples, which is so characteristic for high-temperature hydrothermal systems in oceanic basaltic environments (e.g., Michard 1989). The negative Ce anomalies encountered in some calcites most probably reflect the oxidizing conditions during geode filling to stabilize Ce4+, which cannot be easily incorporated in calcite (e.g., Denniston et al. 1997). Alternatively, the Ce anomaly in calcites may have been inherited from the oxidized Botucatú sandstone. The HREE enrichments recorded by some late-stage calcites (Fig. 7) are characteristic for remobilization processes and REE transport by carbonate complexes in aqueous solutions at neutral to basic pH (e.g., Möller and Morteani 1983; Wood 1990). The REE contents of late-stage gypsum are in most cases below 0.01 times the chondritic values.

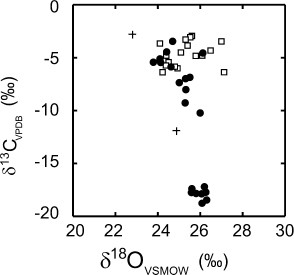

Stable isotope results

The oxygen isotope composition of calcite from all investigated deposits shows a small scatter (δ18OVSMOW=24.9±1.1‰, Table 2 , Fig. 8). There is no significant difference in oxygen isotope composition between early and late-formed calcite. The data suggest that both the temperature of calcite formation and oxygen isotope composition of the aqueous fluid did not change much, i.e., less than ~2 per mil, during filling of the geodes. An alternative explanation for the homogeneity of oxygen isotope values could be an almost complete re-equilibration of isotope ratios in all calcites. However, as oxygen diffusion in calcite is exceedingly slow at ambient temperatures (e.g., Farver 1994) and significant heterogeneity in carbon isotope ratios and REE content is recorded in the calcites (see below), we prefer the former explanation for the observed oxygen isotope homogeneity. Assuming an isotope composition of the calcite-forming fluid that is identical to the enhydros (water filling the cavity of geodes), i.e., δ18OVSMOW=–5.0±0.5‰ (Matsui et al. 1974), and very similar to present-day meteoric waters, we can calculate equilibrium temperatures ranging from 5 to 20 °C using the oxygen isotope fractionation equation of O'Neil et al. (1969) in the system calcite–water. If the oxygen isotope composition of the mineralizing water was 5‰ heavier than the present-day enhydros, maximum formation temperatures would not have exceeded 50 °C. Even by assuming more 18O-enriched water isotope compositions, typical of magmatic waters (δ18OVSMOW=+5 to +10‰), the calculated calcite formation temperature would be in the range between 50 and 100 °C. Oxygen isotope data on amethyst from the Ametista do Sul region (δ18OVSMOW=~29.0‰) have been reported by Juchem et al. (1999). Their values are within ±1‰ to those of agate and colorless macrocrystalline quartz from the same geodes. Equilibrium temperatures for amethyst using the oxygen isotope composition of enhydros (–5‰) by Matsui et al. (1974) are ~25 °C using an extrapolation of the equation by Clayton et al. (1972), or ~40 °C with the equation by Sharp and Kirschner (1994), thus comparable with those derived from calcite considering uncertainties in the fractionation factor quartz–water at low temperatures.

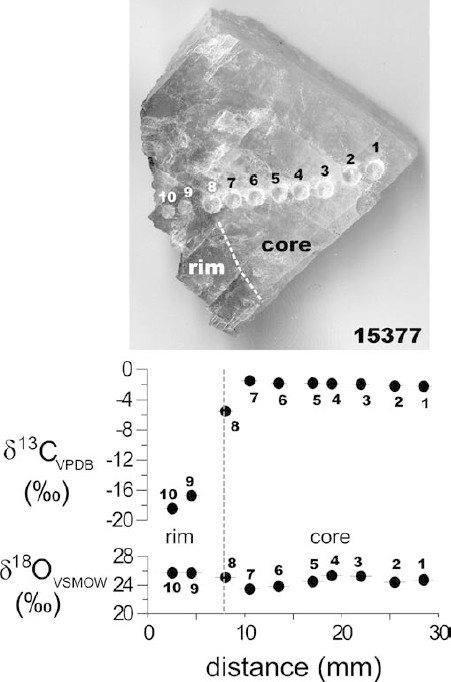

In contrast to oxygen, the carbon isotope values of calcites are characterized by a wide range of δ values from –18.7 to –2.9‰ relative to VPDB (Table 2 ). Early stage calcites (Cc-1 to Cc-3) are relatively heavy and homogeneous with an average δ13CVPDB value of –4.7±1.1‰ (1σ, n=18) in contrast to late stage calcite (Cc-4), which in some cases have heavy carbon isotope values similar to early stage calcite, but in many cases show a trend towards isotopically lighter values with a cluster of around –17.9±0.9‰ (Fig. 8). Figure 9 shows an isotope profile through a late stage (Cc-4), discontinuously zoned calcite crystal (sample 15377, Bortoluzzi) with a translucent whitish core and clear rim. We detect a sudden 15 per mil drop in δ13CVPDB values across the core-rim boundary accompanied by a small 2-permil increase in δ18OVSMOW values. The δ18OVSMOW values within the core also vary within about 2‰. These carbon isotope values suggest that there were at least two sources of carbon available during geode filling. One carbon source characterized by δ13CVPDB calcite values around –5‰ is very probably related to the host basalts (remobilized magmatic carbon) and prevails during the early mineralization stage of all deposits and also the late mineralization stage of some deposits. The second, 13C depleted carbon source becomes available only in some, but not all deposits during late-stage filling with euhedral calcite crystals. The low δ13CVPDB values in some late stage calcites indicate a reduced organic source of carbon. These δ13CVPDB values are, however, lower than those of pedogenic carbonates (e.g., Cerling 1984). We found no correlation of carbon isotope value with REE content or pattern.

The oxygen isotope compositions of two calcites in agate-bearing geodes from the Salto do Jacuí region (δ18OVSMOW=22.6 and 24.6‰) are slightly lower than those from Ametista do Sul indicating either slightly higher formation temperatures or lower δ18OVSMOW values of the calcite-forming waters. Both calcite samples display a wide range of carbon isotope values (–4.2 and –12.8‰) as those from the amethyst-bearing geodes. A contrasting oxygen and carbon isotope analysis (13.0 and –0.3‰, respectively) of an individual calcite from a Brazilian agate geode was published by Götze et al. (2001). Oxygen and hydrogen isotope data of agate from the Rio Grande do Sul region were reported by Blankenburg et al. (1982), Fallick et al. (1987), Blankenburg (1988), and Götze et al. (2001). The range of δ18OVSMOW (24.5–30‰) and δDVSMOW values (–85 to –130‰) is similar to those from Ametista do Sul area, which indicates low equilibration temperatures. Borget (1985) presented comparable oxygen isotope data from Uruguayan amethyst deposits.

The sulfur and oxygen isotope data of sulfate in late stage gypsum δ34SCDT =+5.2 to +6.0‰ and δ18OVSMOW=–2.6 to +5.2‰ (n=5; Table 2 ) are consistent with a derivation of sulfur by oxidation of pyrite from the host basalts under anaerobic to slightly aerobic conditions (van Everdingen and Krouse 1985).

Sr isotopes

The results of our Rb–Sr isotope study on calcite and gypsum from amethyst- and agate-bearing geodes, as well as volcanic host rocks and Botucatú sandstone, are shown in Table 3 and Fig. 10. The 87Sr/86Sr ratios of six geode-bearing basalts from Ametista do Sul range from 0.70561 to 0.70608 and Sr concentrations are high (450±20 ppm). The initial strontium isotope ratios (T=130 Ma) are only slightly lower (0.70553–0.70572) and typical of the high-Ti Pitanga Group basalts (Peate et al. 1992). The eight analyzed calcites from various amethyst geodes show low Sr concentrations (7–60 ppm) and significantly higher 87Sr/86Sr ratios than basalts ranging from 0.70617 to 0.70932, with most samples between 0.7070 and 0.7079. Two samples of late stage gypsum with Sr concentrations of ~135 ppm have slightly higher 87Sr/86Sr ratios (0.70860 and 0.70872) than the majority of calcites. The 87Sr/86Sr ratios of two Botucatú sandstones samples (0.71611 and 0.71617) and rhyodacitic volcanic rocks (0.72220 and 0.72491) from the Salto do Jacuí region are highly radiogenic even when recalculated at 130 Ma (0.71462 and 0.71492 for sandstones, and 0.71787 and 0.71794 for rhyodacites, respectively). The high initial Sr isotope ratios for the rhyodacitic rocks are characteristic for the fractionated magmas of the low-Ti Palmas Group (Peate et al. 1992). Two calcites from agate geodes in these relatively radiogenic rocks have low 87Sr/86Sr ratios of around 0.712.

Variation of 87Sr/86Sr versus Sr (ppm) of calcite, gypsum, geode-hosting basalt from Ametista do Sul, as well as calcite, rhyodacite and Botucatú sandstone from Salto do Jacuí. Analytical errors are smaller than symbols. For rhyodacite and sandstone samples, both initial (T=130 Ma) and present-day 87Sr/86Sr ratios are shown. For other samples, the difference between both ratios is smaller than symbol size

In both areas, calcite Sr isotope ratios are decoupled from their immediate relatively Sr-rich volcanic host rocks. There are two mechanisms that could be responsible for this. Firstly, geode-filling fluids have reacted with other rocks than the immediate wall rocks prior to calcite precipitation, such as the radiogenic Botucatú sandstones in the Ametista do Sul area or basaltic rocks of the Gramado Group (87Sr/86Srinitial ~ 0.707–0.709; Peate et al. 1992) underlying the rhyodacites in the Salto do Jacuí area. This model would suggest a larger scale fluid flow model responsible for filling of the geodes.

Alternatively, differential leaching of certain components with distinct 87Sr/86Sr ratios within the volcanic host rocks could be invoked for the observed Sr isotope decoupling. Leaching experiments on fresh high-Ti basalts with low 87Sr/86Sr ratios (~0.7059) from the northern Paraná basin by Innocent et al. (1997a), using distilled water slightly acidified to a pH of 5.3, have yielded higher 87Sr/86Sr ratios of ~0.708 for the leachates. A source for the radiogenic Sr could be the interstitial differentiated glassy phase in basalts. Assuming that this glass phase had a 87Rb/86Sr ratio of ~3 similar to rhyodacitic rocks, a time span of only about 50 million years after basalt eruption is necessary to increase the 87Sr/86Sr ratio in that easily leachable phase from ~0.705 to ~0.708. Therefore, the radiogenic Sr isotope component in calcites from amethyst geodes could have been derived from such a fractionated interstitial glass phase in the host basalts, only if calcites have formed at least several tens of million years after basalt eruption. We also note that the present-day ground waters in low-Ti Paraná basalts with 87Sr/86Sr ratios of ~0.705 to 0.706 have 87Sr/86Sr ratios of 0.7066 to 0.7072, and also zeolites (heulandite) in geodes in these basalts have 87Sr/86Sr ratios that are identical to calcites in this study (Innocent et al. 1997a).

Discussion: a two-stage model for amethyst geode formation

On the basis of our fluid inclusion, geochemical and isotope study, as well as other data discussed in more detail below, we suggest that the formation of amethyst-bearing geodes in basalts of the Ametista do Sul area, Rio Grande do Sul, Brazil, followed a two-stage process: an early, magmatic stage responsible for the generation of a "protogeode" cavity and a late, very low temperature stage of cavity filling.

Protogeode formation

There can be no question that the cavity of the geode ("protogeode") formed from an immiscible fluid phase of lower density and lower viscosity than the surrounding basaltic magma. We have, however, no clear evidence of the nature of this fluid phase. The formation of an immiscible silica liquid as suggested for example recently by Bossi and Caggiano (1974), Blankenburg (1988), or Merino et al. (1992, 2001), among many others, seems not very likely to us. The present knowledge of co-existing compositions of immiscible silicate liquids in basaltic systems (e.g., Roedder 1984, p. 545ff.), the absence of obvious high-temperature reaction zones with the basaltic magma at the rim of the geodes, and the high viscosity of such silica-rich melts argue strongly against a liquid silica phase as the precursor of the geodes. We refer here to Landmesser (1984, pp. 79–89) for a further discussion of this subject. Merino et al. (2001) recently suggested that reaction of hot magma with surface waters may have played a role in the formation of protogeodes. We emphasize that the Paraná basalts erupted in an extremely arid desert environment dominated by sand dunes (e.g., Bossi and Caggiano 1974; Scherer 2000). Besides, in such a scenario we might expect phreatomagmatic eruption products for which we have no indication in the study area. Thus, an aqueous and/or carbonic vapor phase exsolved from the basaltic lavas seems a more likely candidate for the immiscible fluid responsible for protogeode formation. The high vesicularity at the early chilled top of the mineralized lava flow can be considered as an indicator for its high gas content. Although studies on the initial volatile content of the magma using melt inclusion would be very useful in this respect, the geode-hosting basalts contain only very few (micro-)phenocrysts and, thus, are not suitable for such research.

We also want to draw attention to the peculiar spherical cap shape of most geodes and their alignment in a specific horizon within the upper part of the basalt flow. We suggest that both features can be best explained by the ascent of a fluid with a lower density and viscosity than the surrounding medium, which displays an increasing viscosity from the bottom to the surface. Numerical simulations of such scenarios have been developed by Kukowski and Neugebauer (1990) to explain the occurrence and shape of granitic bodies in the crust, but can be transferred and applied to the formation of protogeodes in basaltic lavas. Exsolving gas bubbles can coalesce very easily because of the relatively low melt viscosities (Sahagian et al. 1989). Upon further ascent, some homogeneous fluid body may eventually split into smaller cap-shaped bodies of similar size stopping all at the same level during ascent. We note that the 10- to 25-m-thick basalt layer below the geode-rich horizon is massive and devoid of amygdales as a result of efficient bubble transport and extraction. Massive bubble coalescence was responsible for the extraordinary large size of some of the amethyst geodes with diameters of more than a meter. The typical spherical cap shape and indented base of the geodes are a hydrodynamic consequence of low melt viscosity and large bubble size and, thus, high Reynolds and Eötvös numbers during bubble ascent (Bhaga and Weber 1981).

In contrast, the protogeode formation at Salto do Jacuí did not involve major bubble transport and coalescence. The host basaltic lava flow is only 4 to 5 m thick and agate-bearing geodes are not concentrated in a specific level within the flow. Furthermore, spherical cap-shaped geodes with an indented base are absent and the maximum size of geodes is smaller than those in the Ametista do Sul area.

Geode filling: temperatures

The filling of the cavities represents the second step in the formation of amethyst geodes. Fluid inclusion and stable isotope data presented here indicate that temperatures during the geode filling period at Ametista do Sul, Brazil, never exceeded 100 °C, consistent with the study of Juchem et al. (1999). A contrasting view has been expressed by Thomas and Blankenburg (1981) and Blankenburg (1988) on the basis of fluid inclusion studies on agate-bearing geodes from Rio Grande do Sul. Although their samples probably were not derived from the Ametista do Sul area and no exact sampling locations were given, their data are briefly discussed here. The authors reported homogenization temperatures of primary fluid inclusions in macrocrystalline quartz ranging from 370 to 420 °C. Some two-phase liquid–vapor inclusions homogenized into the liquid phase, others into the vapor phase, and some exhibit critical homogenization behavior. The primary inclusions showed a considerable variability in their degree of fill (0–100%). As already noted in a short comment by Edwin Roedder in Roedder and Kozlowski (1983, p. 266), the high homogenization temperatures of inclusions could be artefacts of heterogeneous trapping (of air?) and/or subsequent leakage or necking down.

Temperatures of less than 100 °C and a gas-poor aqueous composition of the responsible fluid would further imply that boiling processes, as suggested by Harris (1989), did not play a significant role in the filling process of amethyst geodes. The large differences in δ18O values (~3‰) between microcrystalline quartz (agate) and coarsely crystalline quartz described by Harris (1989) from agate geodes in Etendeka volcanics (Namibia), and interpreted by the same author as indicative for boiling processes at ~120 °C, are not known from geodes in the Ametista do Sul area (Juchem et al. 1999). Additionally, extremely variable REE patterns and radiogenic Sr isotope compositions of carbonates do not favor a high-temperature formation of geode filling shortly after basalt extrusion.

Geode filling: timing

Very few data related to the timing of geode filling have been published. Santos and Bonhomme (1993) have presented K–Ar ages of celadonites in basalts from the Planalto region, Rio Grande do Sul, indicating that this K-rich mineral formed some 10 to 50 million years after basalt eruption. Apophyllites in some geodes gave K–Ar ages of ~113 Ma. A very similar range of ages from celadonite from two areas in the Paraná basin was reported by Innocent et al. (1997a, 1997b) using the Rb–Sr leaching method (80–107 Ma). None of these studies, however, is directly related to amethyst-bearing geodes and the Ametista do Sul area. In some parts of the Paraná basin, hydrothermal circulation with temperatures exceeding 100 °C is recorded by zeolite zonation and especially by the presence of laumonite in the deeper parts of the lava pile (Murata et al. 1987). Recently, Vasconcelos (1998) reported the first 40Ar–39Ar ages of celadonites from amethyst-bearing geodes from Rio Grande do Sul. Celadonite clusters from the base of a geode yielded 80–90 Ma and some celadonite inclusions within the amethyst gave 65–70 Ma, whereas small celadonite nodules in other parts of the basalt flow yielded age clusters ranged from 110 to 133 Ma. These data suggest a long period of celadonite formation in these basalts and final filling of the large amethyst geodes occurred 40 to 60 million years after basalt extrusion. This protracted history of low-temperature hydrous alteration is consistent with variable REE patterns, radiogenic Sr isotope ratios, and variations of carbon isotope values of carbonates in the amethyst geodes.

Geode filling: source of fluids and materials

The fluids that were present during the filling of the amethyst-bearing geodes were low temperature, gas poor aqueous solutions, with very low salt content. Although a magmatic source cannot completely be excluded from our microthermometric and stable isotope data, the very late timing of geode infill with respect to volcanism in that area rather strongly favors a meteoric source for the mineralizing waters.

On the basis of results from our study, the highly reactive interstitial glass phase in the volcanic host rocks is considered as a principal source for silica, but also some other minor components in the geodes, such as calcium (± strontium) and carbon, and possibly also iron, potassium, and rare earth elements. A viable mechanism for silica transport and accumulation in such low temperature systems has been recently suggested by Landmesser (1995, 1998). His concept of "mobility by metastability" is based on the presence of various metastable forms of silica and a sluggish ripening process from amorphous silica via opal and chalcedony to quartz that promotes diffusion and accumulation of Si(OH)4 molecules in pore solutions.

Our Sr isotope and REE data, however, do not exclude some contributions of components from the nearby Botucatú sandstones. We emphasize here that the volcanic rocks in the Paraná basin are underlain by the huge Guaraní or Mercosul aquifer system, one of the world's largest freshwater reservoirs (Montaño et al. 1998; Araújo et al. 1999). The mostly artesian, salt-poor waters with temperatures of up to 70 °C are hosted mainly by Jurassic to Lower Cretaceous eolian sandstones (Botucatú Formation in Brazil, Tacuarembó Formation in Uruguay and Argentina, or Misiones Formation in Paraguay), but also by older Triassic or Permian sandstones. Stable oxygen and hydrogen isotope studies on the aquifer in the northern Argentinian sector reveal meteoric water compositions with δ18OVSMOW values of –5.7±0.7‰ (Montaño et al. 1998), similar to present-day surface waters in the Salto do Jacuí area and the enhydros in the agate geodes (Matsui et al. 1974). Meng and Maynard (2001) have recently evaluated hydrochemical data of the Botucatú aquifer in the State of São Paulo, indicating that the deep ground waters in the interior parts of the basin are precipitating silica (chalcedony) and calcite. The Sr isotope compositions of artesian meteoric waters in Botucatú sandstone aquifers from northern Paraná basin (87Sr/86Sr=~0.712; Innocent et al. 1997a) indicate rapid Sr isotope equilibration with the 87Sr-rich host rocks. Therefore, we cannot exclude contributions of some components (e.g., Sr, REE) derived from the Botucatú sandstones via the artesian Guaraní (Mercosul) aquifer for the filling of the amethyst-bearing geodes.

The shift in δ13C values of calcite from –5±2‰ to –18±1‰ during the late stage of geode filling indicates a significant change in the source of carbon. The heavy carbon isotope values are compatible with remobilized magmatic carbon from basalts, whereas the low values of latest stage calcites indicate the involvement of oxidized organic carbon and probably the exhaustion of the source of heavy magmatic carbon. The presence of celadonite, goethite, amethyst, and gypsum in the geodes indicates that oxidizing conditions prevailed throughout the mineralization sequence. As the δ13C values of latest stage calcites are lower than those of pedogenic carbonates (Cerling 1984), we suspect that that the 13C-depleted carbon derives from oxidation of organic matter in sedimentary rocks of the Paraná basin underlying the basalts. This scenario would also imply a significant change in the pattern of meteoric fluid flow in the Paraná basin.

But has the Guaraní (Mercosul) aquifer system been active, artesian, and filled with meteoric waters during the Late Cretaceous as well? The geologic history and ground water evolution of the Guaraní (Mercosul) aquifer system is outlined in detail by Araújo et al. (1999). They suggest that the initial freshwater recharge over most of the basin from its eastern and southeastern margin and the broad-scale establishment of the present flow net and hydraulic gradients started at 110–90 Ma as a consequence of initial uplift in the coastal Serra do Mar Mountains and of increased rainfall (Goldberg and Garcia 2000). The uplift peaked at 95±5 Ma in the Serra do Mar Mountains and total erosion is estimated to be 3,000 m (Araújo et al. 1999). This rapid uplift at the eastern border of the basin is related to the opening of the southern Atlantic Ocean ("rift shoulder effect") and is accompanied by alkaline intrusions and hydrothermal activity in that region (e.g., Santos and Bonhomme 1993). During deposition of the Upper Cretaceous continental sediments of the Bauru Group (88–65 Ma) in the center of the Paraná basin, the groundwater flow system below the Serra Geral volcanics probably did not change significantly (Araújo et al. 1999). At present, the top of the main Guaraní (Mercosul) aquifer in the Ametista do Sul area is located ~1,000 m below the surface with a potentiometric head of approximately 250 m above sea level and has a temperature of approximately 50 °C (Araújo et al. 1999).

Key factors responsible for economic amethyst mineralization

Our study suggests that a combination of very specific conditions leading to (1) the formation of large and abundant protogeodes in the thick basaltic São Gabriel lava flow, and (2) a suitable hydrogeological setting for geode infill was necessary to form the amethyst deposits in the Ametista do Sul area, Brazil. We can only speculate why other basaltic lava flows in that area do not contain economic amethyst mineralization, although some flows host subeconomic amethyst occurrences (Scopel et al. 1998). The absence of large protogeodes in the barren or subeconomic flows might indicate that the initial volatile content of the magma was too low, or the viscosity of the melt, which varies as a function of temperature, chemical composition, and volatile content, was not suitable for efficient bubble transport, extraction and coalescence. The lava flow velocity and the distance from the feeder zone could be other critical factors related to this problem. Finally, we emphasize that permeability, fracture density, interstitial glass content, and earlier alteration events of the geode-hosting basalts are other important parameters that may influence economic amethyst mineralization. Further studies are necessary to characterize mineralized and barren or subeconomically mineralized basalt flows in the Paraná basin.

Conclusions

The most likely scenario for the formation of the geodes in basalts of the Ametista do Sul area is a two-stage process.

During an initial magmatic stage, protogeode cavities formed from an immiscible fluid phase of lower density and viscosity than the basaltic magma. In a second post-magmatic stage, the cavities were partly filled with celadonite, agate, colorless and amethystine quartz, calcite, and gypsum at temperatures of less than 100 °C. A gas-poor aqueous fluid of meteoric origin was involved in the transport of silica, calcium, carbon, and minor elements, which were most probably leached from the highly reactive interstitial glass fraction of the host basalt and possibly with contributions from the arenaceous sedimentary rocks (e.g., Botucatú sandstone).

Geode infill is considered as a long-lasting process that probably started with the onset of sustained freshwater recharge to the Guaraní (Mercosul) aquifer system in the Mid-Cretaceous and ended, according to preliminary 40Ar–39Ar data of Vasconcelos (1998), ~40–60 million years after basalt extrusion. More geochronological data are needed to better constrain the timing and duration of mineralization. We consider the variability of REE patterns and carbon isotope data, as well as radiogenic Sr isotope ratios, in calcite as a consequence of such a protracted history of geode infill with accompanying changes in the composition of mineralizing solutions. The circulation of the meteoric fluids was predominantly driven by the artesian Guaraní (Mercosul) aquifer hosted by the Botucatú sandstones in the footwall of the volcanic sequence.

References

Araújo LM, França AB, Potter PE (1999) Hydrogeology of the Mercosul aquifer system in the Paraná and Chaco-Paraná Basins, South America, and comparison with the Navajo–Nugget aquifer system, USA. Hydrogeol J 7:317–336

Arnold M (1986) A propos des inclusions fluides monophasées dites métastables à température ambiente. C R Acad Sci Paris Ser II 303:459–461

Audétat A, Günter D (1999) Mobility and H2O loss from fluid inclusions in natural quartz crystals. Contrib Mineral Petrol 137:1–14

Balitsky VS (1978) Les conditions de formation des améthystes et leur croissance artificielle. Bull Minéral 101:383–386

Bau M (1991) Rare-earth element mobility during hydrothermal and metamorphic fluid–rock interaction and the significance of the oxidation state of europium. Chem Geol 93:219–230

Bhaga D, Weber ME (1981) Bubbles in viscous liquids: shapes, wakes and velocities. J Fluid Mech 105:61–85

Blankenburg HJ (1988) Achat. Eigenschaften, Genese, Verwendung. VEB Deutscher Verlag für Grundstoffindustrie, Leipzig

Blankenburg HJ, Pilot J, Werner CD (1982) Erste Ergebnisse der Sauerstoffisotopenuntersuchungen an Vulkanitachaten und ihre genetische Interpretation. Chem Erde 41:121–135

Bodnar RJ, Reynolds TJ, Kuehn CA (1985) Fluid inclusion systematics in epithermal systems. Rev Econ Geol 2:73–97

Borget JN (1985) Contribution à l'étude de la genèse des minéralisations siliceuses associées aux roches basaltiques du nord-ouest de l'Uruguay. PhD Thesis, University of Clermont-Ferrand, France

Bossi J, Caggiano W (1974) Contribución a la geología de los yacimientos de amatistas en el departamento de Artigas (Uruguay). XXVII Congresso Brasileiro de Geologia, Porto Alegre, vol 3, pp 301–318

Cassedanne J (1988) L´amethyste au Brésil. Classification et localisation des gites – inclusions. Rev Gemmol AFG 94:15–18

Cerling TE (1984) The stable isotopic composition of modern soil carbonate and its relationship to climate. Earth Planet Sci Lett 71:229–240

Clayton RN, O'Neil JR, Mayeda TK (1972) Oxygen isotope exchange between quartz and water. J Geophys Res 77:3057–3067

Corrêa TE, Koppe JC, Costa JFCL, Moraes MAL (1994) Caracterização geológica e critérios de prospecção de depósitos de ametista tipo Alto Uruguai, RS. Anais do XXXVIII Congresso Brasileiro de Geologia, Camboriú, vol 2, pp 137–138

Denniston RF, Shearer CK, Layne GD, Vaniman DT (1997) SIMS analyses of minor and trace element distributions in fracture calcite from Yucca Mountain, USA. Geochim Cosmochim Acta 61:1803–1818

Fallick AE, Jocelyn J, Donnelly T, Guy M and Behan C (1985) Origin of agates in volcanic rocks from Scotland. Nature 313:672–674

Fallick AE, Jocelyn J, Hamilton PJ (1987) Oxygen and hydrogen stable isotope systematics in Brazilian agates. In: Rodríguez-Clemente R, Tardy Y (eds) Geochemistry and mineral formation in the Earth surface. Consejo Superiór de Investigaciónes Científicas, Madrid, pp 99–117

Farver JR (1994) Oxygen self-diffusion in calcite: dependence on temperature and water fugacity. Earth Plant Sci Lett 121:575–587

Gatter I (1987) Fluid inclusion studies in the polymetallic ores of Gyöngyösoroszi (North Hungary) – spatial and temporal evolution of ore-forming fluids. Chem Geol 61:169–181

Goldberg K, Garcia AJV (2000) Palaeobiogeography of the Bauru Group, a dinosaur-bearing Cretaceous unit, northeastern Parana basin, Brazil. Cretaceous Res 21:241–254

Goldstein RH, Reynolds TJ (1994) Systematics of fluid inclusions in diagenetic minerals. SEPM Short Course 31:1–199

Götze J, Tichomirowa M, Fuchs H, Pilot J, Sharp ZD (2001) Geochemistry of agates: a trace element and stable isotope study. Chem Geol 175:523–541

Harris C (1989) Oxygen isotope zonation of agates from Karoo volcanics of the Skeleton Coast, Namibia. Am Mineral 74:476–481

Hecht L, Freiberger R, Gilg HA, Grundmann G, Kostitsyn YA (1999) Rare earth element and isotope (C, O, Sr) characteristics of hydrothermal carbonates: genetic implications for dolomite-hosted talc mineralization at Göpfersgrün (Fichtelgebirge, Germany). Chem Geol 155:115–130

Innocent C, Michard A, Malengreau N, Loubet M, Noack Y, Benedetti M, Hamelin B (1997a) Sr isotopic evidence for ion-exchange buffering in tropical laterites from the Paraná, Brazil. Chem Geol 136:219–232

Innocent C, Parron C, Hamelin B (1997b) Rb/Sr chronology and crystal chemistry of celadonites from the Paraná continental tholeiites, Brazil. Geochim Cosmochim Acta 61:3753–3761

Juchem PL (1999) Mineralogia, geologia e genêse dos depósitos de ametista da região do Alto Uruguaí, Rio Grande do Sul. PhD Thesis, University of São Paulo

Juchem PL, Fischer AC, Bello RM, Svisero DP (1994) Inclusões fluidas em ametistas da região do Alto Uruguaí Rio Grande do Sul. Bolet Resum XXXVIII Congr Bras Geol, Camberiú, pp 649–650

Juchem PL, Fallick AE, Bettencourt JS, Svisero DP (1999) Geoquímica isotópica de oxigênio em geodos mineralizados a ametista da região do Alto Uruguaí, RS – um estudo preliminar. 1. Símposio sobre vulcanismo e ambientes associados, Gramado [Abstr]

Kukowski N, Neugebauer HJ (1990) On the ascent and emplacement of granitoid magma bodies – dynamic–thermal numerical models. Geol Rundsch 79:227–239

Landmesser M (1984) Das Problem der Achatgenese. Mitt Pollichia 72:5–137

Landmesser M (1995) Mobility by metastability: silica transport and accumulation at low temperatures. Chem Erde 55:149–176

Landmesser M (1998) "Mobility by metastability" in sedimentary and agate petrology: applications. Chem Erde 58:1–22

Leinz V (1949) Contribução à geologia dos derrames basálticos do sul do Brasil. FFCL-USP Bol C Geol 5:1–61

Lieber W (1985) Pseudomorphose von Quarz nach Anhydrit. Der Aufschluss 36:143–144

Matsui E, Salati E, Marini OJ (1974) D/H and 18O/16O ratios in waters contained in geodes from the Basaltic Province of Rio Grande do Sul, Brazil. Geol Soc Am Bull 85:577–580

McArthur JR, Jennings EA, Kissin SA, Sherlock RL (1993) Stable-isotope, fluid-inclusion and mineralogical studies relating to the genesis of amethyst, Thunder Bay, Amethyst Mine, Ontario. Can J Earth Sci 30:1955–1969

McCrea JM (1950) On the isotopic chemistry of carbonates and a paleotemperature scale. J Chem Phys 18:849–857

McLennan SM (1989) Rare earth elements in sedimentary rocks: influence of provenance and sedimentary processes. Rev Mineral 21:1209–1264

Meng SX, Maynard JB (2001) Use of statistical analysis to formulate conceptual models of geochemical behavior: water chemical data from the Botucatu aquifer in São Paulo state, Brazil. J Hydrol 250:78–97

Merino E, Wang Y, Deloule E (1992) Aluminium: catalyst, crystal deformer, and dye: self organizational crystallization of quartz in agates and amethyst geodes, Paraná flood basalts, Brazil. In: Kharaka Y, Maest (eds) Water–rock interaction. Balkema, Rotterdam, pp 1075–1077

Merino E, Wang Y, Deloule E (1995) Genesis of agates in flood basalts: twisting of chalcedony fibers and trace-element geochemistry. Am J Sci 295:1156–1176

Merino E, Dutta P, Ripley EM, Wang Y (2001) High-temperature, closed-system origin of agates in basalts: new evidence. Geol Soc Am Annu Meeting, Boston [Abstr]

Meunier A, Formoso MLL, Patrier P, Chies JO (1988) Altération hydrothermale de roches volcaniques liée à la genèse des améthystes – Bassin du Paraná – sud du Brésil. Geochim Brasiliensis 2:127–142

Michard A (1989) Rare earth element systematics in hydrothermal fluids. Geochim Cosmochim Acta 53:745–750

Möller P, Morteani G (1983) On the geochemical fractionation of rare earth elements during the formation of Ca-minerals and its application to problems of the genesis of ore deposits. In: Augustithis SS (ed) The significance of trace elements in solving petrogenetic problems and controversies. Theophrastus Publications, Athens, pp 747–791

Möller P, Morteani G, Dulski P (1984) The origin of the calcites from Pb–Zn veins in the Harz mountains, Federal Republic of Germany. Chem Geol 45:91–112

Möller P, Lüders V, Schröder J, Luck J (1991) Element partitioning in calcite as a function of solution flow rate: a study on vein calcites from the Harz Mountains. Miner Deposita 26:175–179

Montaña JR, Bossi J (1993) Nuevos datos para prospección de ametistas en geodas basálticas. Ejemplo en Curtinas (Tacuarembó, Uruguay). Congresso Geologia Economica de Cordoba, Argentina, pp 372–383

Montaño J, Tujchneider O, Auge M, Fili M, Paris M, D'Elía M, Pérez M, Nagy MI, Collazo P, Decoud P (1998) Acuíferos Regionales en América Latina. Sistema Acuífero Guaraní. Capítulo argentino-uruguayo. Centro de Publicationes, Universiad Nacional del Litoral, Santa Fe, Argentina

Murata KJ, Formoso MLL, Roisenberg A (1987) Distribution of zeolites in lavas of southeastern Paraná basin, state of Rio Grando do Sul, Brazil. J Geol 95:455–467

O'Neil JR, Clayton RN, Mayeda TK (1969) Oxygen isotope fractionation in divalent metal carbonates. J Chem Phys 51:5547–5558.

Peate DW, Hawkesworth CJ, Mantovani SM (1992) Chemical stratigraphy of the Paraná lavas (South America): classification of magma types and their spatial distribution. Bull Volcanol 55:119–139

Piccirillo EM, Melfi AJ (eds) (1988) The Mesozoic flood volcanism of the Paraná Basin, petrogenetic and geophysical aspects. Universidade de São Paulo, Instituto Astronômico e Geofísico

Piccirillo EM, Comin-Chiaramonti P, Melfi AJ, Stolfa D, Bellieni G, Marques LS, Giaretta A, Nardy AJR, Pinese JPP, Raposo MIB, Roisenberg A (1988) Petrochemistry of continental flood basalt–rhyolite suites and related intrusives from the Paraná Basin (Brazil). In: Piccirillo EM, Melfi AJ (eds) The Mesozoic flood volcanism of the Paraná Basin, petrogenetic and geophysical aspects. Universidade de São Paulo, Instituto Astronômico e Geofísico, pp 285–295

Renne PR, Ernesto M, Pacca IG, Coe RS, Glen JM, Prevot M, Perrin M (1992) The age of Paraná flood volcanism, rifting of Gondwanaland, and the Jurassic–Cretaceous boundary. Science 258:975–979

Robinson RW, Norman DI (1984) Mineralogy and fluid inclusion study of the Southern Amethyst vein system, Creede mining district, Colorado. Econ Geol 79:439–447

Roedder E (1967) Metastable superheated ice in liquid–water inclusions under high negative pressures. Science 155:1413–1417

Roedder E (1984) Fluid inclusions. Rev Mineral 12:1–644

Roedder E, Kozlowski A (eds) (1983) Fluid inclusion research, vol 16. Proceedings of Comission on Ore-Forming Fluids in Inclusions. University of Michigan Press, Ann Arbor

Rossman GR (1994) Colored varieties of the silica minerals. Rev Mineral 29:433–467

Sahagian D, Anderson AT, Ward B (1989) Bubble coalescence in basalt flows: comparison of a numerical model with natural examples. Bull Volcanol 52:49–56

Santos RP, Bonhomme MG (1993) Datação K/Ar de argilas associadas às mineralizações e aos processos diagenéticos, em relação com a história da abertura do oceano Atlântico Sul. Rev Bras Geosci 23:61–67

Scherer CMS (2000) Eolian dunes of the Botucatu Formation (Cretaceous) in southernmost Brazil: morphology and origin. Sediment Geol 137:63–84

Scopel RM, Gomes MEB, Formoso MLL, Proust D (1998) Derrames portadores de ametistas na região Frederico Westphalen-Iraí-Planalto-Ametista do Sul, RS-Brasil. Actas II Congresso Uruguayo de Geologia, Punta del Este, pp 243–248

Sharp ZD, Kirschner DL (1994) Quartz–calcite oxygen isotope thermometry: a calibration based on natural isotopic variations. Geochim Cosmochim Acta 58:4491–4501

Stewart K, Turner S, Kelley S, Hawkesworth CJ, Kirstein L, Mantovani M (1996) 3-D, 40Ar–39Ar geochronology in the Paraná continental flood basalt province. Earth Planet Sci Lett 143:95–109

Szubert EC, Orlandi FV, Shintaku I (1978) Geologia dos jazimentos de ametista do Alto Uruguai. Guias de prospecção. XXX Congresso Brasileiro de Geologia, Recife, vol 4, pp 1350–1356

Thomas R, Blankenburg HJ (1981) Erste Ergebnisse über Einschlussuntersuchungen an Quarzen aus Achatmandeln und Kugeln basischer und sauerer Vulkanite. Z Geol Wiss 9:625–633

Turner S, Regelous M, Kelley S, Hawkesworth CJ, Mantovani M (1994) Magmatism and continental break-up in the South Atlantic: high precision 40Ar–39Ar geochronology. Earth Planet Sci Lett 121:333–348

Ueda A, Krouse HR (1987) Direct conversion of sulphide and sulphate minerals to SO2 for isotope analyses. Geochem J 20:209–212

Van Everdingen RO, Krouse HR (1985) Isotope composition of sulphates generated by bacterial and abiological oxidation. Nature 315:395–396

Vasconcelos PM (1998) 40Ar/39Ar dating of celadonite and the formation of amethyst geodes in the Paraná Continental Flood Basalt Province. Am Geophys Union 1998 fall meeting, San Francisco, F933 [Abstr]

Wang Y, Merino E (1990) Self-organizational origin of agates: banding, fiber twisting, composition, and dynamic crystallization model. Geochim Cosmochim Acta 54:1627–1638

Wang Y, Merino E (1995) Origin of fibrosity and banding in agates from flood basalts. Am J Sci 295:49–77

Wood SA (1990) The aqueous geochemistry of the rare-earth elements and yttrium: 2. theoretical predictions of speciation in hydrothermal solutions to 350 °C at saturation vapor pressure. Chem Geol 88:99–125

Yang KH, Yun SH, Lee JD (2001) A fluid inclusion study of an amethyst deposit in the Cretaceous Kyongsan Basin, South Korea. Mineral Mag 64:477–487

Acknowledgements.

This paper is dedicated to Prof. Peter Möller on the occasion of his 65th birthday. We are indebted to the Volkswagen Stiftung for financial support. Many thanks to the garimpeiros from the Ametista do Sul area for allowing us to enter their properties and mines and for help in the sampling. We are also grateful for technical assistance in the laboratory from K. Holzhäuser, R. Beiderbeck, and V. Ruttner (TU München), A. Voropayev (Hydroisotop, Schweitenkirchen) and P. Dulski (GFZ Potsdam). P. Juchem and P. Vasconcelos drew our attention to published preliminary results of their ongoing studies. Fruitful discussions with J. Koppe are also highly appreciated. The careful corrections, critical commentaries, and some useful hints to further references by A. Fallick, B. Lehmann, V. Lüders, and two anonymous reviewers have significantly improved our manuscript. We also thank A. Cheilletz for rapid editorial handling.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Editorial handling: A. Cheilletz

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Gilg, H.A., Morteani, G., Kostitsyn, Y. et al. Genesis of amethyst geodes in basaltic rocks of the Serra Geral Formation (Ametista do Sul, Rio Grande do Sul, Brazil): a fluid inclusion, REE, oxygen, carbon, and Sr isotope study on basalt, quartz, and calcite. Miner Deposita 38, 1009–1025 (2003). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00126-002-0310-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00126-002-0310-7