#!/usr/bin/env python

# coding: utf-8

# <!--BOOK_INFORMATION-->

# <img align="left" style="padding-right:10px;" src="figures/PDSH-cover-small.png">

# *This notebook contains an excerpt from the [Python Data Science Handbook](http://shop.oreilly.com/product/0636920034919.do) by Jake VanderPlas; the content is available [on GitHub](https://github.com/jakevdp/PythonDataScienceHandbook).*

#

# *The text is released under the [CC-BY-NC-ND license](https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/3.0/us/legalcode), and code is released under the [MIT license](https://opensource.org/licenses/MIT). If you find this content useful, please consider supporting the work by [buying the book](http://shop.oreilly.com/product/0636920034919.do)!*

#

# *No changes were made to the contents of this notebook from the original.*

# <!--NAVIGATION-->

# < [Aggregations: Min, Max, and Everything In Between](02.04-Computation-on-arrays-aggregates.ipynb) | [Contents](Index.ipynb) | [Comparisons, Masks, and Boolean Logic](02.06-Boolean-Arrays-and-Masks.ipynb) >

# # Computation on Arrays: Broadcasting

# We saw in the previous section how NumPy's universal functions can be used to *vectorize* operations and thereby remove slow Python loops.

# Another means of vectorizing operations is to use NumPy's *broadcasting* functionality.

# Broadcasting is simply a set of rules for applying binary ufuncs (e.g., addition, subtraction, multiplication, etc.) on arrays of different sizes.

# ## Introducing Broadcasting

#

# Recall that for arrays of the same size, binary operations are performed on an element-by-element basis:

# In[4]:

import numpy as np

# In[5]:

a = np.array([0, 1, 2])

b = np.array([5, 5, 5])

a + b

# Broadcasting allows these types of binary operations to be performed on arrays of different sizes–for example, we can just as easily add a scalar (think of it as a zero-dimensional array) to an array:

# In[6]:

a + 5

# We can think of this as an operation that stretches or duplicates the value ``5`` into the array ``[5, 5, 5]``, and adds the results.

# The advantage of NumPy's broadcasting is that this duplication of values does not actually take place, but it is a useful mental model as we think about broadcasting.

#

# We can similarly extend this to arrays of higher dimension. Observe the result when we add a one-dimensional array to a two-dimensional array:

# In[7]:

M = np.ones((3, 3))

M

# In[8]:

M + a

# Here the one-dimensional array ``a`` is stretched, or broadcast across the second dimension in order to match the shape of ``M``.

#

# While these examples are relatively easy to understand, more complicated cases can involve broadcasting of both arrays. Consider the following example:

# In[9]:

a = np.arange(3)

b = np.arange(3)[:, np.newaxis]

print(a)

print(b)

# In[10]:

a + b

# Just as before we stretched or broadcasted one value to match the shape of the other, here we've stretched *both* ``a`` and ``b`` to match a common shape, and the result is a two-dimensional array!

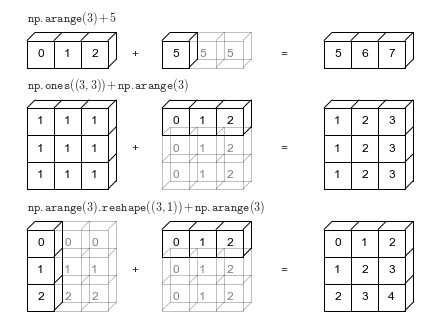

# The geometry of these examples is visualized in the following figure (Code to produce this plot can be found in the [appendix](06.00-Figure-Code.ipynb#Broadcasting), and is adapted from source published in the [astroML](http://astroml.org) documentation. Used by permission).

#

# The light boxes represent the broadcasted values: again, this extra memory is not actually allocated in the course of the operation, but it can be useful conceptually to imagine that it is.

# ## Rules of Broadcasting

#

# Broadcasting in NumPy follows a strict set of rules to determine the interaction between the two arrays:

#

# - Rule 1: If the two arrays differ in their number of dimensions, the shape of the one with fewer dimensions is **padded** with ones on its leading (left) side.

# - Rule 2: If the shape of the two arrays does not match in any dimension, the array with shape equal to 1 in that dimension is **stretched** to match the other shape.

# - Rule 3: If in any dimension the sizes disagree and neither is equal to 1, an error is raised.

#

# To make these rules clear, let's consider a few examples in detail.

# ### Broadcasting example 1

#

# Let's look at adding a two-dimensional array to a one-dimensional array:

# In[11]:

M = np.ones((2, 3))

a = np.arange(3)

# Let's consider an operation on these two arrays. The shape of the arrays are

#

# - ``M.shape = (2, 3)``

# - ``a.shape = (3,)``

#

# We see by rule 1 that the array ``a`` has fewer dimensions, so we pad it on the left with ones:

#

# - ``M.shape -> (2, 3)``

# - ``a.shape -> (1, 3)``

#

# By rule 2, we now see that the first dimension disagrees, so we stretch this dimension to match:

#

# - ``M.shape -> (2, 3)``

# - ``a.shape -> (2, 3)``

#

# The shapes match, and we see that the final shape will be ``(2, 3)``:

# In[12]:

M + a

# ### Broadcasting example 2

#

# Let's take a look at an example where both arrays need to be broadcast:

# In[13]:

a = np.arange(3).reshape((3, 1))

b = np.arange(3)

# Again, we'll start by writing out the shape of the arrays:

#

# - ``a.shape = (3, 1)``

# - ``b.shape = (3,)``

#

# Rule 1 says we must pad the shape of ``b`` with ones:

#

# - ``a.shape -> (3, 1)``

# - ``b.shape -> (1, 3)``

#

# And rule 2 tells us that we upgrade each of these ones to match the corresponding size of the other array:

#

# - ``a.shape -> (3, 3)``

# - ``b.shape -> (3, 3)``

#

# Because the result matches, these shapes are compatible. We can see this here:

# In[14]:

a + b

# ### Broadcasting example 3

#

# Now let's take a look at an example in which the two arrays are not compatible:

# In[15]:

M = np.ones((3, 2))

a = np.arange(3)

# This is just a slightly different situation than in the first example: the matrix ``M`` is transposed.

# How does this affect the calculation? The shape of the arrays are

#

# - ``M.shape = (3, 2)``

# - ``a.shape = (3,)``

#

# Again, rule 1 tells us that we must pad the shape of ``a`` with ones:

#

# - ``M.shape -> (3, 2)``

# - ``a.shape -> (1, 3)``

#

# By rule 2, the first dimension of ``a`` is stretched to match that of ``M``:

#

# - ``M.shape -> (3, 2)``

# - ``a.shape -> (3, 3)``

#

# Now we hit rule 3–the final shapes do not match, so these two arrays are incompatible, as we can observe by attempting this operation:

# In[16]:

M + a

# Note the potential confusion here: you could imagine making ``a`` and ``M`` compatible by, say, padding ``a``'s shape with ones on the right rather than the left.

# But this is not how the broadcasting rules work!

# That sort of flexibility might be useful in some cases, but it would lead to potential areas of ambiguity.

# If right-side padding is what you'd like, you can do this explicitly by reshaping the array (we'll use the ``np.newaxis`` keyword introduced in [The Basics of NumPy Arrays](02.02-The-Basics-Of-NumPy-Arrays.ipynb)):

# In[17]:

a[:, np.newaxis].shape

# In[18]:

M + a[:, np.newaxis]

# Also note that while we've been focusing on the ``+`` operator here, these broadcasting rules apply to *any* binary ``ufunc``.

# For example, here is the ``logaddexp(a, b)`` function, which computes ``log(exp(a) + exp(b))`` with more precision than the naive approach:

# In[19]:

np.logaddexp(M, a[:, np.newaxis])

# For more information on the many available universal functions, refer to [Computation on NumPy Arrays: Universal Functions](02.03-Computation-on-arrays-ufuncs.ipynb).

# ## Broadcasting in Practice

# Broadcasting operations form the core of many examples we'll see throughout this book.

# We'll now take a look at a couple simple examples of where they can be useful.

# ### Centering an array

# In the previous section, we saw that ufuncs allow a NumPy user to remove the need to explicitly write slow Python loops. Broadcasting extends this ability.

# One commonly seen example is when centering an array of data.

# Imagine you have an array of 10 observations, each of which consists of 3 values.

# Using the standard convention (see [Data Representation in Scikit-Learn](05.02-Introducing-Scikit-Learn.ipynb#Data-Representation-in-Scikit-Learn)), we'll store this in a $10 \times 3$ array:

# In[20]:

X = np.random.random((10, 3))

# We can compute the mean of each feature using the ``mean`` aggregate across the first dimension:

# In[21]:

Xmean = X.mean(0)

Xmean

# And now we can center the ``X`` array by subtracting the mean (this is a broadcasting operation):

# In[22]:

X_centered = X - Xmean

# To double-check that we've done this correctly, we can check that the centered array has near zero mean:

# In[23]:

X_centered.mean(0)

# To within machine precision, the mean is now zero.

# ### Plotting a two-dimensional function

# One place that broadcasting is very useful is in displaying images based on two-dimensional functions.

# If we want to define a function $z = f(x, y)$, broadcasting can be used to compute the function across the grid:

# In[24]:

# x and y have 50 steps from 0 to 5

x = np.linspace(0, 5, 50)

y = np.linspace(0, 5, 50)[:, np.newaxis]

z = np.sin(x) ** 10 + np.cos(10 + y * x) * np.cos(x)

# We'll use Matplotlib to plot this two-dimensional array (these tools will be discussed in full in [Density and Contour Plots](04.04-Density-and-Contour-Plots.ipynb)):

# In[25]:

get_ipython().run_line_magic('matplotlib', 'inline')

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

# In[26]:

plt.imshow(z, origin='lower', extent=[0, 5, 0, 5],

cmap='viridis')

plt.colorbar();

# The result is a compelling visualization of the two-dimensional function.

# <!--NAVIGATION-->

# < [Aggregations: Min, Max, and Everything In Between](02.04-Computation-on-arrays-aggregates.ipynb) | [Contents](Index.ipynb) | [Comparisons, Masks, and Boolean Logic](02.06-Boolean-Arrays-and-Masks.ipynb) >